The Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) has recently adopted a transfer of floor area ratios (TFAR) process. The Council Committee on Housing and Redevelopment, part of the Los Angeles City Council, is currenlty reviewing TFAR process with two main focuses: 1) the "nexus" issue and 2) the pricing issue. The article is authored by Charles E. Loveman Jr. and Larry Kosmont who are real estate consultants with Kosmont & Associates specializing in entitlement services.

“For developers, this pricing scheme only adds more uncertainty to this process.”

The Los Angeles City Council is currently reviewing the proposed transfer of floor area ratios (TFAR) process adopted by the Community Redevelopment Agency. Two issues of concern to the Council Committee on Housing and Redevelopment are the so-called “nexus” issue, pertaining to the legality of the TFAR mechanism with respect to A.B.1600, and the pricing issue. This article focuses solely on the pricing questions, leaving the discussion of the “nexus” problem to the City Attorney.

With respect to TFAR pricing, three questions should be asked: What is a fair price for unused development rights, from both the buyer’s (recipient’s) and seller’s (donor’s) perspective? What public policy objectives should be accomplished by the TFAR mechanism? And how can the pricing of TFAR be structured so that the private sector is encouraged to achieve the desired public policy outcomes?

The TFAR ordinance was adopted by City Council in May, 1988, and provides the “exclusive procedure to transfer floor area,” within the CBD for all projects involving a transfer in excess of 50,000 sq. ft. The pricing of this TFAR transaction began 21 months ago with a recommendation by the CRA staff to adopt a proposed methodology for the valuation of TFAR.

Underlying the proposed TFAR pricing are several fundamental assumptions. First, this abstract commodity, transferable floor area, is related to the underlying price of land per FAR square foot. The purchase of density at a recipient site is analogous to the purchase of additional land area at the same location. At some price, a developer would be indifferent between either buying additional land (assuming its availability) and developing their total property at the “as of right” density, or paying cash to another property owner and/or CRA for the right to build at a level in excess of the “as of right” entitlement. Thus this price of choosing the TFAR route should be less than the price of buying additional land, assuming such land was available.

Another assumption is that to encourage the developer to choose the TFAR route, the TFAR price must be further discounted from the underlying land price. In fact, CRA recommends a 50% discount.

This deep discount is no accident. Because of the historic pricing of the “density variation” (the forerunner to today’s TFAR ordinance), in which density was transferred at approximately the opportunity cost of the donor to forego development, land prices were effectively overvalued in proportion to development rights.

For instance, assume a developer could afford to pay $60 per FAR sq. ft for development rights for a 12:1 FAR project. The $60 figure represents a weighted average cost for both the portion of density attributable to land and to the transfer. Historically, the additional 6 FAR’s, which took the developer from a 6:1 to a 12:1 density, could be purchased for $20 a square foot. Therefore, if the total “blended” cost could not exceed $60 per FAR sq. ft., and half the density can be purchased for $20, a developer could afford to pay up to $100 for the land.

In fact, this process is exactly what happened. Because the portion of the transaction above the “as of right” level was priced so cheaply relative to its true market value, the “as of right” or land portion was overpriced relative to market. However, developers were indifferent to this anomaly, provided that the “blended” rate did not exceed a supportable threshold.

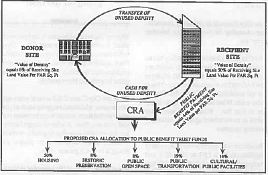

Thus, when the CRA undertook to create a pricing methodology for TFAR, a specific objective of that effort was to price TFAR not at the donor’s opportunity cost for foregoing development but at the recipient’s value of receiving the additional density. This objective led directly to another, namely given that the value of not using the density at the donor is less than the value of utilizing it for the recipient, this difference should be captured by the “public” in the form of a cash payment directly to the CRA. This cash payment is called the Public Benefit Payment (PBP).

Finally, according to the CRA, the value of unused development rights at a typical donor site is essentially zero in today’s market. This assumption is fundamental to the entire pricing proposal, and derives from the hypothesis that all donor sites are, as stated in the words of one TFAR Task Force member, “assumed to be flophouses on Main Street.” So this logic goes, the only economic use at this prototype donor site is ground floor retail. With no other economic uses, the unused density in current market conditions has no value. Accordingly, the only way to derive a value for this commodity is to assume that, one day in the future, today’s “flophouse” will be tomorrow’s office development site. So, after accounting for inflation, risk, and so on, the CRA concludes that an unused square foot of floor area at the donor site is worth about $5 per FAR sq. ft., or about 6% of today’s current office land price per FAR sq. ft.

Therefore, we ask “What’s wrong with this picture?”

- From the recipient’s point of view, there is too much uncertainty with respect to the total cost of the transaction.

- From the donor’s point of view, the methodology prices all but the most marginal land uses out of the picture.

- From a public policy point of view, the proposal is inefficient in terms of directing financial resources to create the maximum amount of public benefit.

With respect to the problem of uncertainty from the recipient’s point of view, the TFAR transaction clearly breaks into distinct components: a public benefit payment made directly to the CRA, and the purchase of unused density from some donor source. The only certainty in the pricing structure is that the PBP will be 44% of the recipient’s underlying land value per FAR sq. ft. With respect to the price for the purchase of unused density, the CRA is careful to emphasize that they are not intervening to set a price between buyer and seller. From the CRA’s point of view, the two portions of the transaction are completely unrelated, and it is not the CRA’s business to regulate what a buyer should pay a seller for unused density.

In fact, the belief that these two parts of the transaction are unrelated is untrue. The calculation of public benefit at 44% of FAR recipient site land value depends entirely upon an assumption of how much the unused density is worth to each party. By the CRA's own calculations, a fair price for unused density for the recipient is 50% of underlying land value per FAR sq. ft. Given that the CRA has fixed the public benefit fee at 44%, the recipient’s purchase only makes sense if it is equal to or less than 6% of their land value.

But for the recipient, the ability to find a seller at the 6% price is unknown. On the other hand, to pay more than 6% would mean exceeding the affordable “blended” rate. For developers, this pricing scheme only adds more uncertainty to this process.

With respect to the donor site, is the valuation methodology fair from their perspective? In a word, no. The unusual conclusion that the unused density at the donor site has no economic value is possibly true only if the donor site is located in the worse areas of the CBD. If the universe of donor sites were solely to limited to those very marginal locations, there would be some validity to the CRA’s pricing structure. However, what happens when the donor site is located in a better area?

For the CRA, pricing the donor’s density at 6% of the recipient site’s land value means that every potential donor is assumed to be on Main Street. From the CRA’s point of view, the advantage of this assumption is that the portion of the transaction going directly to them, the public benefit payment, is maximized. However, a corollary to that outcome is a message to the marketplace that a potential donor that sits in a strong market location, say an historic building within an area bounded by Olive, Fifth, Eighth and Flower, can’t compete with the Main Street use to sell its unused density cheap enough to justify the transaction.

Put another way, if the going rate for donor density is set by the CRA at $5 per FAR sq. ft., and the land value per sq. ft. at the well-located donor site property is $25 per sq. ft., this well-located historic building would be foolish to sell an asset worth $25 for $5. The signal to the marketplace is, tear down your historic building, or scrap your plans to develop housing, or redevelop your existing open space, because only then can you earn a market return on your transferable density.

To which the CRA staff will protest, “Not true. Some donors have sold their unused development rights for $40 per sq. ft., after taking into account a direct pass-through of the public benefit payment”. Which brings us to our third problem, namely, the only way to win at this game is to position yourself to get the PBP directly passed through to the donor.

However, there are no ground rules for how and when the CRA will make the necessary findings to permit the pass-through. The PBP pass-through is purely a discretionary act on the CRA’s part, with no written guidelines to inform potential donors or recipients how to play. Our same well-located historic building is thus still at risk, because without any guidelines, it’s most likely that the risk-averse recipient side of the transaction will become impatient and choose to go with the sure thing of buying density direct from the CRA.

In conclusion, we should give the CRA credit where it is due. Pricing at the recipient site’s value is a major innovation in the application of the TDR mechanism. But, having accomplished this breakthrough, let’s not forget that the fundamental purpose of TDR programs are to enable below market land uses to compete on a level playing field with the highest and best market uses.

Don’t fix the pricing system so that the largest and most reliable portion of the transaction is the payment of cash to the CRA. Instead, if we want to build housing or preserve historic buildings, identify upfront the housing and historic sites which will qualify as donors, clarify the public benefit pass-through system, and let the recipient side of the transaction bid up the price of the donor’s unused density asset to pay for the public objective.

- Log in to post comments