Since 1980 Brenda Levin, President and Principal of Levin & Associates Architects, has been a leader in historic preservation across LA, establishing her firm as most adept at balancing historic intent and context with modern structure and renovation. In May Levin spoke at the AIA National Convention in Washington, DC, describing her firm’s approach to two of Los Angeles’ most icon historic and religious buildings: St. Vibiana’s Cathedral and the Wilshire Boulevard Temple. TPR is pleased to present the following excerpts of Levin’s remarks, which illustrate preservation’s role in reinvesting in today’s communities.

Brenda Levin

"Political cooperation in the preservation of the cathedral was critical to the success of the project. Religious properties clearly have a rich history of adaptive reuse, and heritage tourism is one of the fastest-growing industries in the world. Historic preservation is, of course, one of the most successful strategies for economic renewal in America" -Brenda Levin

Brenda Levin: Tonight we’ll look at two case studies: one, an adaptive reuse of an historic cathedral into an event venue; and the other, the preservation of a historic sanctuary and a master plan for an entire city block for continued religious and community use. Both represent significant revitalization efforts and substantial investment in their respective communities.

I just want to remind everyone that Los Angeles began as a pueblo, and in 1857 the population was only 1,610 people. In 1873, there were 5,750. By 1940, the population had grown to 1.5 million and in 2007 to 3.8 million. We now exceed over 4 million, so you can see that there’s been rapid growth in a short period of time.

Our first project is the Cathedral of St. Vibiana, which was the parish of the Archdiocese from 1876 to 1994, and from 2008 has served as a venue for events. A new Cathedral, designed by Rafael Moneo, was built about six city blocks to the north.

But in 1859, Los Angeles was chosen as the seat of the Monterrey-Los Angeles Catholic Diocese. Shortly thereafter, Church officials proposed building the mother church on Main Street between 5thand 6thStreet. Much excitement was generated by the construction of the city’s first cathedral, to be named St. Vibiana, patron saint of the diocese. At the laying of the cornerstone in 1869, more than 3,000 people took part in a religious procession down Main Street, and Thaddeus Amat, Bishop of Los Angeles and president of Saint Vincent’s College, delivered a sermon in Spanish and English. Church leaders, however, decided that the original location was far too removed from the population center, and in May 1871 groundbreaking began on the site at 2ndand Main.

The cathedral was modeled on the Church of the Puerto de San Miguel in Barcelona, Spain. It was completed in 1876. However, St. Vibiana’s Cathedral was wider than its prototype and had a belltower—a very visible belltower, tripartite in organization, rising the entire height and beyond of the building. Its original design feature was by architect Ezra Kysor, who is known as LA’s first professional architect. At the end of the 19thcentury, the cathedral was an imposing edifice of brick and wood construction. At the time of its completion, it could hold within its dramatic sanctuary a significant proportion of the city’s young population.

The cathedral was not structurally altered until 1922 when John C. Austin, LA’s most prominent architect of the period, completed an extensive renovation. At that time, ceilings were changed, the north and south exterior walls were plastered, and new art glass panels were installed in the windows. The original brick façade was removed and replaced with Indiana limestone and the frontal portion of the cathedral was extended to the sidewalk. Austin’s architectural modifications are now considered character-defining features of historic significance and represent an expression of culture and building technology of the 20’s in LA.

During the middle decades of the century, as the city grew, various alternative sites were examined for a possible new larger cathedral. Limited changes to the interior of the cathedral were made after Vatican II to reflect the new clerical focus, primarily extending the altar area forward into the congregation.

In 1994, the Northridge earthquake damaged the cathedral, which led the Archdiocese to close it due to safety concerns. In January 1995, the Archdiocese announced plans to build a new cathedral on the St. Vibiana site and began demolishing the old cathedral. However, preservationists blocked the demolition, citing the building’s landmark status, and demanded that the old cathedral be incorporated into a new structure. This led to a lengthy legal battle between the Archdiocese and preservationists. Much of the debate over the future of the cathedral had focused on the extent of the damage, which was quite substantial. The repair cost that the Archdiocese estimated was $18 to $20 million. Citing the high cost of bringing the old cathedral to modern sizing standards and their argument that they would never be able to solicit donations for renovation as opposed to new construction, the Archdiocese began looking for a new cathedral site. In December 1996, it purchased 5.6 acres from LA County and opened the new cathedral in 2008.

In January 1997, the Los Angeles Conservancy commissioned the USC School of Architecture to direct a team to study reuse of the cathedral. The school assembled several diverse teams of sixteen firms with expertise in architecture, planning, preservation, development cost estimating, and economic feasibility, and examined the site of 100,000 square feet at the nexus of the historic core of Little Tokyo and the Civic Center to determine highest and best use. The conclusions of the study were quite comprehensive. The cathedral could be rehabilitated for a number of uses; the most prolific of which was to repurpose the building and site for a hotel use given the dearth of hotel rooms in Little Tokyo. The estimated cost to seismically retrofit the building was $5 million.

Political cooperation in the preservation of the cathedral was critical to the success of the project. Religious properties clearly have a rich history of adaptive reuse, and heritage tourism is one of the fastest-growing industries in the world. Historic preservation is, of course, one of the most successful strategies for economic renewal in America. The demolition of a 121-year-old cathedral, one of the oldest structures in downtown Los Angeles, would have been an irreversible loss to the history, culture, and physical character of the city.

We ultimately embarked on a building stabilization effort, particularly of the belltower, with the insertion of new steel structure and new foundations, new seismic shear walls, new plywood sheathing to tie together two discontinuous roofs, and the cleaning, renovation, and preservation of the historic materials on the exterior and interior of the building. To make this all possible, a developer named Tom Gilmore bought four buildings on the corner of 4thand Main in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles and, under the aegis of the adaptive reuse ordinance, converted those commercial buildings to residential uses. Through those efforts, he was identified as someone committed to this area, and Gilmore was able to purchase St. Vibiana’s from the Archdiocese.

The state of California provided $4 million for the seismic retrofit and renovation. The Los Angeles Conservancy received federal dollars from Congresswoman Roybal-Allard, who made a $1 million grant to the project. Our design team proceeded with the seismic retrofit, the adaptive reuse, and Gilmore, to this day, operates the facility as a multipurpose event site. Residential and retail development in the area contributes to making it a lively well-used space. It stands now proud, in the context of the historic and the new downtown, and it is used for fashion shows, corporate events, private parties, weddings, etc. While it is no longer a religious site, it has been preserved and is a very important contributor to the historic core.

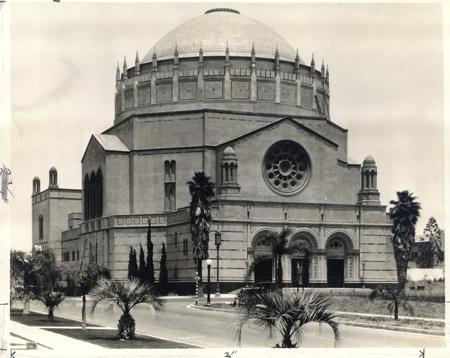

In contrast to St. Vibiana’s, we are going to look at Wilshire Boulevard Temple, formerly known as Congregation B'nai B'rith. It was founded in 1862, with a mission to provide Jews of Los Angeles with organized religious services, Jewish education for young people and adults, and to provide for the social needs of Jews and others in the community. The congregation was first housed at Temple and Broadway. In the 1880s, it moved to Temple and Hope, and then ultimately west to the 3600 block of Wilshire Boulevard Temple. It has subsequently built an auxiliary campus to the main site at Wilshire and Harvard, on the westside of town.

B’nai B’rith was renamed Wilshire Boulevard Temple in1929, when the congregation dedicated their new building. In 1924, the area around Wilshire and Western was fairly unbuilt, and was considered the western most outpost of the city. However by 1947, the corner of Wilshire and Western had been built out with the Wiltern Theater and the 12-story Pellissier Building, marking the westward expansion of the city.

The landmark Wilshire Boulevard Temple building is associated with many of the men who invented the motion picture industry. Many of them were legends: the Warner brothers were members, Louis B. Mayer, the Laemmle’s and Irving Thalberg. But by the 1970s, the Jewish population had substantially moved west in an exodus from the city center. Many of the historic sanctuaries in the city were sold as congregations moved out of the central core.

The Temple was designed by A.M. Edelman with consulting architects Allison and Allison, is Moorish in design, with some Byzantine exterior details. It is reminiscent of early Renaissance but essentially is a totally modern composition. It’s a steel-framed building with cast-in-place concrete walls and floor, with a concrete shell dome that’s a 100 feet in diameter and rises 110 feet off the floor.

I’m going to speak about the preservation issues before discussing the master plan. Every aspect of the building suffered from deferred maintenance. The good news was that the Temple had not been insensitively altered; the bad news was that no significant improvements or repairs had been made over the years to improve its continued life.

The building is constructed of steel, cast concrete, precast concrete, cast in place concrete, marble and granite. Every single surface exhibited deterioration – water infiltration and causing potential falling hazards. Every surface and material has been fully inspected and documented, and repair procedures developed. The exterior dome, originally covered in mosaic-patterned tile, obviously leaked and was covered in copper in the 1940’s. We determined that those tiles were still in place, although not viable for reuse. They would have had to be removed, a waterproof membrane installed on the concrete shell, and the tiles replaced. A suspended plaster coffered ceiling exhibited sign of efflorescence. A large piece of plaster fell to the sanctuary floor one evening causing the sanctuary to be closed until a safety net could be installed. The dome is being restored and painted to match the original color scheme.

In researching historic photos it was determined that the base plinth stone, now delaminating, was once black, as were the marble bands interspersed on the plaster facades, when the building opened. Over the years that stone calcified, developed a gray surface, and visually disappeared into the building. We are replacing the base with black granite, and are honing and sealing the marble bands to bring them back to their original black and white coloring.

The building has been totally stripped of all paint and coatings. It wasn’t the yellow color originally; it appears to have been a brownish-taupe color, which is the coating color we selected as the restored finish. The kasota stone exterior steps are being repaired. The rose window is a beautiful composition of cast-stone surrounds and leaded glass. It has, as well as the other leaded glass windows, been de-installed for conservation. The cast-stone, which had substantive cracks, is being repaired and the glass is being cleaned and re-leaded at Judson Studios in Highland Park, one of the most well-known art-glass restorers in the country.

One of the building’s structural challenges is that the very heavy dome sits on a steel-framed drum, and walls. Although the building never had substantive earthquake damage, the Structural Engineer performed a Tier 1 and a Tier 2 report and a model to determine the appropriate seismic retrofit. The studies demonstrated that the diagonal walls of the sanctuary’s octagonal shape were the most vulnerable and showed potential failure. Our solution was to insert four new shear walls from the basement to the top of the drum. The challenge was that there was decorative historic material on both sides of the walls, requiring a decision of which historic fabric could be more easily removed and replaced. We are also inserting steel columns between the high tripartite windows on the east and west, and adding carbon fiber on the low roof.

Below the sloped sanctuary floor is a plenum with vent openings, which is how ventilation was originally supplied to the building – a very common practice in supplying air in theaters, particularly in the early 20thcentury. Air blown over blocks of ice created cool-moving air which rose up through the openings in the floor. We are reusing this plenum space to supply air-conditioning and heating to the sanctuary. The challenge, of course, is to develop a system where the air is distributed in a way in which the acoustic envelope is not violated. Therefore, this whole plenum will be lined with acoustic treatments, as are the ducts. And any equipment or piping suspended from the ceiling will be on acoustic-isolation hangers.

The sanctuary is one of the most spectacular rooms in Los Angeles. It seats 1800 in the balcony and on the main floor. Commissioned by Warner Bros. studio head Jack Warner and painted by artist Hugo Ballin, the murals, which ring the sanctuary, depict the journey of Jewish people from biblical times to their arrival in the United States in the late 20’s. Such depictions, even in a reform temple, were rare at the time, due to a strict interpretation of the Second Commandment’s prohibition against graven idols. The same conservators who worked on Ballin murals at Griffith Observatory are restoring the murals.

Another design intervention is modifications to the bema to make it more accessible. The bema is the raised platform that contains the Ark, which houses the Torahs. It’s a two-part platform: we are lowering the lower platform to create ramps along the sides of the sanctuary so that everyone can participate in the service and have access to the Ark. We have also reoriented the steps from the bimah directly into the congregation.

There are extraordinary, beautiful bronze original chandeliers that are to be restored and relamped. We have also designed an entirely new lighting scheme, which is an interesting challenge in a room of this size: 100’ in diameter, a 100’ tall decorative dome coffered ceiling. We’re adding high intensity lighting in the oculus - which is a not an oculus that is open to the air but enclosed at the top of the dome. The fixtures will be clamped onto a structural steel ring positioned to graze down the dome and onto the floor. We are adding the same fixtures into eight new light niches, two niches on each of the diagonal walls, which will graze up to intersect those shining down.

The Temple leadership felt that however important, that just restoring the sanctuary would not necessarily revitalize the community or bring people back to this historic site other than for the major Jewish holidays. The current Rabbi really wanted to revitalize this area, known as Koreatown in Los Angeles, by building a campus to support the original mission of Wilshire Boulevard Temple to provide for the spiritual and educational needs of the congregation, and the societal needs of the community.

The Temple owns the entire city block, which includes two historic buildings, the sanctuary/auditorium and event space, and a two-story school building. Our firm has developed a master plan that organized the site into districts: a community and religious district, a school district, and, of course in Los Angeles, a parking and social service district. The plan is focused on an internal pedestrian street, with buildings oriented around courtyards that reference the siting of the historic buildings. Phase 1 includes the restoration of the sanctuary. Ultimately, the parking structure will serve 500 cars, with the upper level to be used as the play area for the school – remember, this is a tight urban campus. The design of the new buildings reference the regulating lines of the historic building and ensures the dome’s visibility from any point on the campus by employing setbacks and stepped forms.

Over a period of time, most likely within ten years, the Temple will develop the entire site to transform it and return it to a center for Jewish life. The leadership hopes to enhance the religious, educational, and community-based activities it currently provides for not only the congregation but for the community at large.

Each of these projects was a result of a tipping point. As Malcolm Gladwell explains: a moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point, a place where the unexpected becomes the expected, where radical change is more than a possibility – it is a certainty. He frames this comment in biological terms, as an epidemic. It is an applicable model to the evolution of and revitalization of these two projects. Had Tom Gilmore not purchased four buildings on the corner of 4thand Main and built on two other creative developers’ decades of work – Wayne Ratkovich and Ira Yellin – he would not have been able to purchase St. Vibiana’s and he would not have been able to secure the funds to create the multipurpose event space that it has become today. And had Wilshire Boulevard Temple not witnessed a return to an urban lifestyle, in the center city, from the westward expansion, by young singles and young families and, therefore, an expanding lively Jewish community, it would not have been possible to imagine that one could not only restore this building but to also think about building four new buildings on this Korea town site.

This is a lesson in longevity, staying with a project for a very long time. I’ve been an architect for 32 years, and I would say that up until about 10 years ago it would have been hard to believe that Wilshire Boulevard Temple would have supported such a reinvestment, and that St. Vibiana’s would not have been lost forever. Thank you.

- Log in to post comments