MIR is pleased to excerpt the following from an article, Aligning Transit and Real Estate: An Integrated Financial Strategy, by Will Fleissig of Communitas Development Inc. and Ian Carlton of the University of California, Berkeley. Prepared for the Center for Transit Oriented Development, Fleissig and Carlton acknowledge the mixed record of TOD in meeting financial and social expectations. While the article does focus on emerging models leading to successful development, MIR is looks here at “TOD 1.0’, focused on federal funding formulas that are disconnected from real estate market forces.” Though many praise recent shift by developers towards building along transit nodes, this along cannot ensure a successful living or commercial space.

Will Fleissig

"Urban, walkable, and mixed-use TOD projects are overburdened with additional costs when compared to competing real estate investments."

TOD 1.0 – “Current Disconnect”

TOD implementation and financing discussions have historically focused on station planning and real estate development processes. Conversations have focused on relatively high TOD real estate costs. Planners have focused on creating zoning and design guidelines, economic development professionals have provided developer subsidies to spur TOD construction, and developers have balanced government and community desires with real estate markets and their investors’ expectations. Little attention has been paid to the transit implementation process that actually determines the real estate market and surroundings in which transit stations are constructed. Transit implementation generates difficulties for TOD and it is a major reason that built TOD is successful only on rare occasions. This section will describe why we think TOD to-date, TOD 1.0, has performed below expectations.

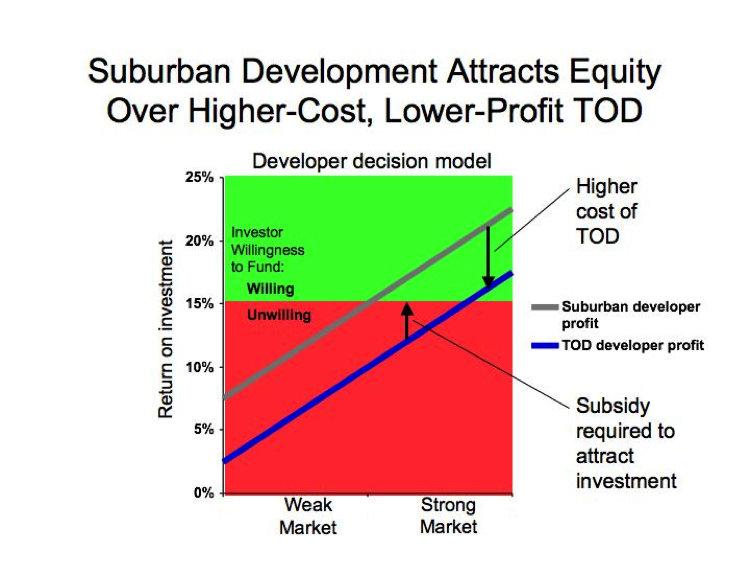

TOD Costs Are Higher Than Comparable Suburban Investment Options

Urban, walkable, and mixed-use TOD projects are overburdened with additional costs when compared to competing real estate investments. TOD has significantly more expense than other suburban or infill real estate product and has difficulty competing for investment dollars.

These additional cost factors include:

• Urban land v. “Greenfield” land

• Upgraded Urban utilities v. “Greenfield” utilities

• Environmental cleanup issues v. Unblemished sites or low-impact prior uses

• Mid and High-rise construction v. Low-rise construction

• Mixed Use buildings v Single Use buildings

• Structured parking v. Surface parking

• Higher level of design finish through design review process v. standard finishes with minimal city review

• Complex street network infrastructure v. Minimal networks

• Diverse pedestrian, auto, and transit accommodations v. Auto-oriented design

Figure 1 – TOD Investment vs. Suburban/Other Infill

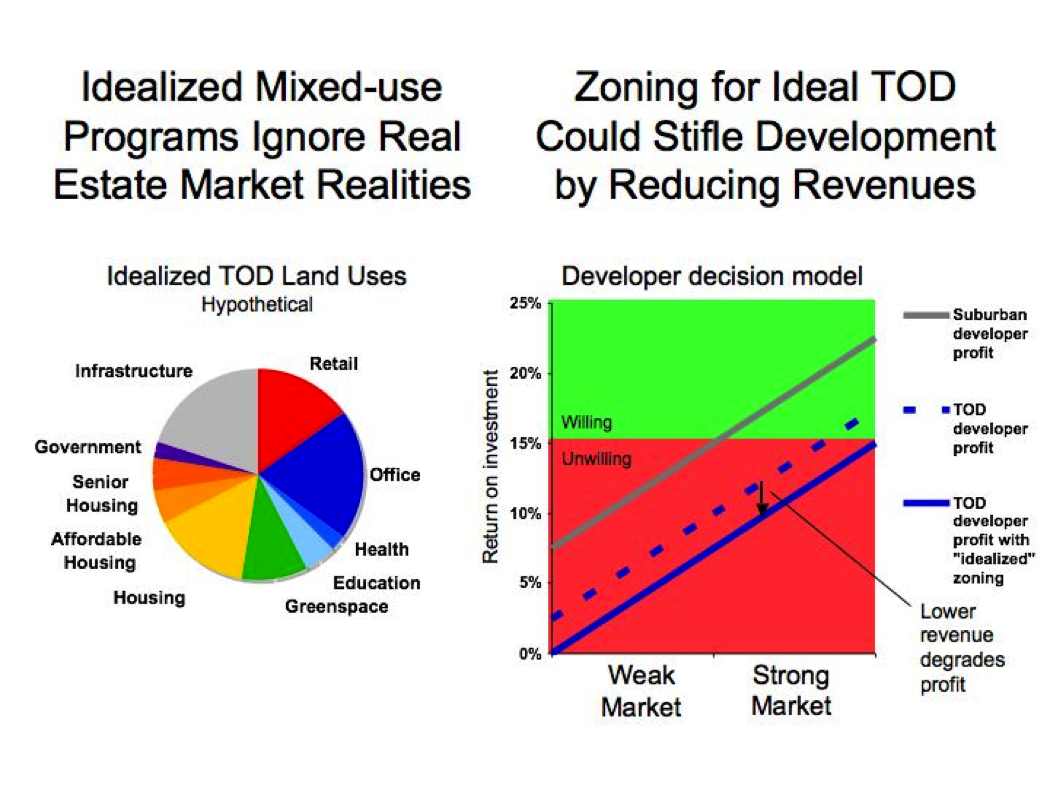

Limited Influence of Zoning

While a necessary local policy step, station area planning and zoning does not overcome the high costs of building TOD projects. In fact, the zoning applied to TOD areas often adds more complexity and cost with master plan requirements, phasing options for future development, and layers of additional standards for landscaping, parks, streets, and buildings. Many proponents of station area development believe that station planning & zoning would produce community-benefiting TOD. However, zoning is just one factor that is taken into account in determining where and how equity is allocated by real estate professionals:

• Zoning / Density / Building Standards

• Available Infrastructure / Utilities

• Auto Access

• Market Rents / Demand

• Pipeline of Planned Projects/ Absorption

• Cost Parameters

• Environmental Issues / Cleanup

• Site Visibility / Adjacent Land Development

• Community Requirements

As shown in Figure 2, zoning that requires idealized TOD may increase costs, dampen profits, and actually decrease the potential that TOD will be implemented.

Figure 2 – Idealized TOD Zoning Can Impact TOD Potential

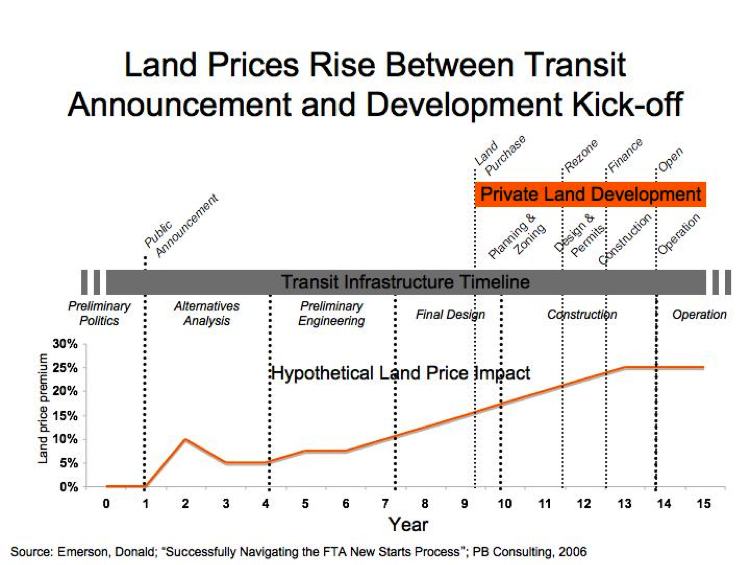

Asynchronous Timing Can Impact Development Potential

People familiar with transit projects are not surprised that it can take anywhere from 10 to 15 years from initial feasibility to opening day. The multiple engineering milestones from early Alternatives Analysis to Record of Decision; the political challenges facing local jurisdictions who must approve planning alternatives, environmental impacts, and revenue measures; the local dynamics among environmentalists, housing advocates, developers, neighborhood and business interests regarding corridor alignments and station locations; and the changing funding decisions made by Congress and the FTA all combine to lengthen the transit building process when using Federal funds. The typical time frame is realistic, yet daunting.

Compare 10-15 years for transit implementation to a typical timeframe for development projects – site acquisition, entitlements, design, construction, and initial leasing takes between 3-5 years. This time differential between transit and development discourages most developers from focusing on future station areas as viable investments. It’s difficult to justify spending much time, effort or money on site acquisition for TOD’s when the payoff is so far down the road. Investors can often find more profitable investment vehicles.

Because transit is a decade away, few developers are at the table when transit is initially planned. Without an advocate, TOD real estate objectives can be lost amongst a myriad of other political concerns, funding criteria, and expert opinions. It is no surprise that difficulties arise when developers arrive on the scene just before transit opens and find that transit engineers, urban planners, and other interests spent upwards of a decade building transit systems in areas that are not suitable for real estate development.

In addition, if land markets are viable, land speculators often arrive on the scene soon after transit implementation intentions are revealed. Utilizing debt financing and private equity, speculators buy and sell land on short cycles and drive up prices during early stages of transit planning.

Figure 3 – Transit Infrastructure v. Real Estate Development Timeline

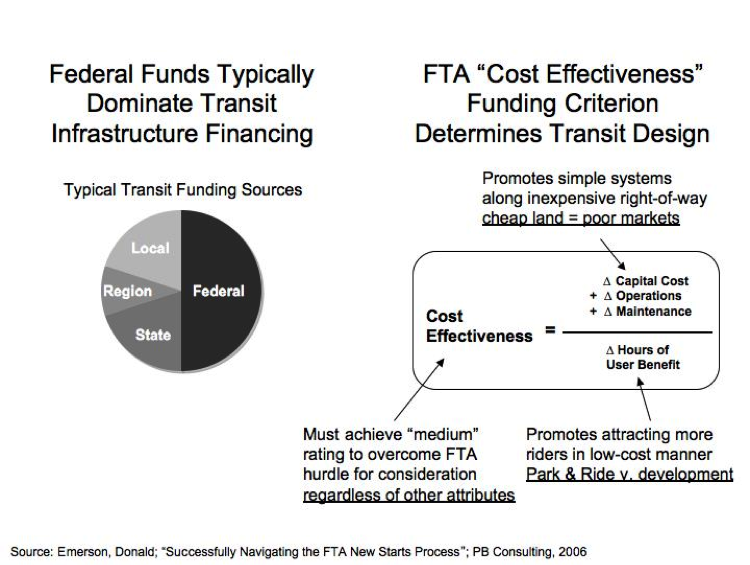

Dominant Transit Financing Source Promotes Station Locations in Poor Real Estate Markets

As seen in Figure 4, government financing for transit infrastructure is dominated by federal funds from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). The FTA issues funds through a competitive process and transit system designers adjust their proposals to meet the FTA guidelines.

Figure 4 – Federal “Cost Effectiveness” Criterion Dominates Transit Infrastructure Design

FTA decision makers focus heavily on their “Cost Effectiveness” calculation. Essentially a cost-benefit ratio, the calculation promotes the lowest cost means to attract the greatest ridership. Transit designers are given incentives to build a low-cost park & ride parking spot – assumed to generate one round trip per day – rather than pay a higher land price to construct a station near an existing development. In doing so, federal officials are pushing transit towards low-cost land – low-cost land indicating a poor real estate market – rather than pushing transit towards better real estate markets where land is more expensive and TOD potential is much greater.

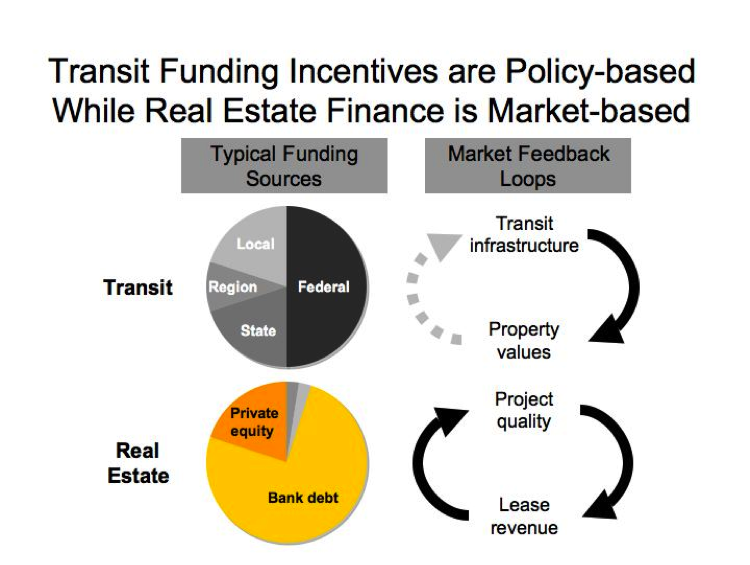

Transit Implementation and Real Estate Development Financing Incentives Are Misaligned

The disconnect between transit implementation objectives and real estate development incentives is perpetuated by the distinct financing structure of each. Transit finance is dominated by government sources that are allocated competitively to projects with the lowest risk and lowest cost. On the other end of the spectrum, real estate development finance focuses on balancing risk and costs with rewards.

Figure 5 – TOD 1.0 Financing Components and Missing Market Feedback Loop

The outcome of this financing disconnect is exhibited in vacant land and acres of park & ride lots surrounding transit stations throughout the country. Because policy-driven transit finance pushes transit towards low-cost land in poor real estate markets, TOD is often infeasible around these stations.

Transit and Real Estate Implementation Involve a Complex Array of Players

Numerous parties are involved in TOD implementation – both delivering transit and developing real estate. The process includes government entities at the federal, state, regional, and local level. Private players include for-profit and non-profit entities. Special interest groups and advocates are also involved in TOD implementation.

A growing influence on transportation policy and investment has emerged with greater force – an expanding group of “special issue advocates” who look beyond the goal of increased mobility to advance their particular issue. TOD proponents include social justice organizations, affordable housing professionals, “good planning” coalitions and open space preservation advocates. Today, these players play a regular role in the process and are often provided a seat at the transit planning table from the outset to help transit plans achieve greater political support.

The demands these various groups place on transit and TOD often degrade real estate revenues, increase project costs, and erode real estate profits. This can make TOD projects relatively unattractive real estate investments. While all parties play an important role in TOD implementation, their number and diversity of interest can create complexity that contributes to unsuccessful TOD outcomes.

Public Sector Cannot Justify Adequate TOD Subsidies

Many developers will tell you that a subsidy could make their project profitable, attract investors, and spur TOD development. And this is probably true. However, all of the sizable hindrances working against TOD require a counterbalancing subsidy of equal or greater magnitude. Still, many jurisdictions have found the means to partially subsidize many TOD sites.

Successful first-generation TOD 1.0 has relied on various public sector subsidy and assistance strategies to help offset costs. Subsidized debt financing has reduced debt burdens for TOD projects. Likewise, community development grants, state grants, and tax increment (TIF) bonds have been successfully incorporated into TOD funding. Government-owned property has also been contributed to help lower land costs.

Several strategies have been suggested to alter this systemic challenge of higher development costs. Chris Leinberger, an urban strategist with the Brookings Institution, has suggested that real estate cultivate a new level of patient private equity with different return and timing expectations.[2] In this way, TOD projects can prioritize long-term returns, cover greater up-front costs, and attract standard short-term debt financing. This approach offers a strategy to address the timing and infrastructure burden typical for station area development. Given near term lending and market conditions, this approach is not likely to be tested for several years.

Conventional TOD Assistance:

- Direct financial grants for:

◦ Housing affordability

◦ Infrastructure

◦ Land procurement

◦ Minority-Owned Business Development

- Publicly funded below-market rate debt financing

- Low-interest municipal/infrastructure bond financing

- Tax increment financing

- Below-market rate transfer or lease of government owned land

- Expedited building permits and permitting costs

TOD 1.0 Has Lacked The Recipe for Success

As described above, TOD 1.0 suffers from cost, timing, and transit funding issues. Most fundamental, transit is often built in market areas that are not suitable for TOD development. Walkable, sustainable, and equitable TOD has considerable cost burdens relative to other development types and either extensive subsidies or superior market locations can help TOD generate profit levels that make it a relatively attractive investment. Subsidies work – even in the worst markets – but are limited in scope and scale. Ultimately, successful TOD requires good markets, good station areas, and excellent coordination between numerous parties all dedicated to its success.

To reach a new level of execution success, TOD will have to better adapt to the unique adversity it faces. Transit planners and engineers will need to be cognizant of the real estate markets where they propose to build stations and governments will need to work with the private sector to overcome timing and cost related issues. If TOD is to succeed consistently, a new paradigm is required.

- Log in to post comments