The Westside Urban Forum hosted a May panel, “The Art of Getting to Maybe: Why has Updating LA’s Community Plans become Impossible?” examining the failure of the Hollywood Community Plan. Despite years of community engagement, the plan was challenged by community groups, thrown out by a judge, and repealed by the Los Angeles City Council in compliance with a court order. Moderated by Michael Woo, Dean of the College of Environmental Design, Cal Poly Pomona and former Los Angeles City Councilmember representing Hollywood, the panelists—Jane Usher, former Senior Assistant City Attorney and Planning Commission President; Dale Goldsmith, Partner, Armbruster, Goldsmith & Delvac; and Tom Donovan, West Los Angeles Area Planning Commissioner and Attorney—answer the “Why” question, citing a lack of political will behind community plans and the uniqueness of Hollywood. TPR shares the following excerpts from the Forum.

Michael Woo

“It pains me a little bit that the judge issued his verdict and everyone assumes city hall was clueless. Ladies and gentlemen, they were not.” –Jane Usher

“The issue I have is that the Planning Department brought a bread knife to a gun battle.” –Dale Goldsmith

Michael Woo: The organizers of this morning’s WUF panel described the judge’s decision in the case of the Hollywood Community Plan as “just the latest debacle” in a series of setbacks in the LA city planning process. Is this hyperbole? Or is this an accurate description of the state of LA city planning in 2014?

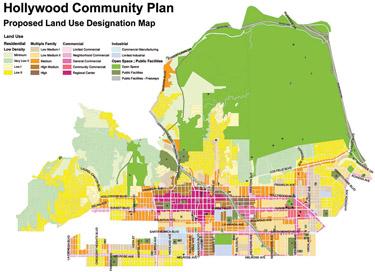

Before we get to our panel, let’s review the facts. State law requires cities to update their general plans periodically. LA’s general plan is divided into 35 community plans, with some of those community plan areas being larger than some of the 88 cities in LA County. In the case of Hollywood, the plan was last updated in 1988 when somebody named Mike Woo represented Hollywood on the LA City Council.

When Gail Goldberg became planning director in 2006, she proposed to embark on a program of “real planning,” updating three community plans at a time and including Hollywood in the first round of updates. There was a clear rationale for this since the existing Hollywood Community Plan was outdated, there was a lot of development pressure in Hollywood, and the advent of the Metro Red Line had changed the context for planning and development.

After that came years of staff work and more than 120 community meetings. The new community plan proposed denser, taller developments, emphasizing areas by the new transit stations. It also added 13,000 new residential units over a period of about 18 years. That plan was adopted by the LA City Planning Commission and adopted by the LA City Council in June 2012, but three community groups decided to sue to stop the plan. They alleged that the city had violated CEQA. They alleged that the city had relied upon unfounded population projections and failed to consider alternatives. Then in December 2013 Superior Court Judge Allan J. Goodman ruled with the plaintiffs and threw out the plan. As a result, about 18 projects entered the legal zone known as limbo and were to be considered under the provisions of the 1988 Hollywood Community Plan.

So what does this all mean? Jane Usher, we’ll start with you. When you were President of the LA City Planning Commission, you embraced the phrase “Do Real Planning,” articulating a list of planning principles, which at least temporarily got the attention of developers. Is it possible to have real planning or good planning without updated community plans?

Jane Usher: As Michael knows, because he served on the commission with me, what we observed very quickly was that our professional planners were embattled. They had outdated community plans. They had a culture where professional planning judgment ran into conflict with political judgment. We wrote the set of “Do Real Planning” principles as a stopgap until the community plan updating process started. We drew from ideas identified by the planners—they did not come out of thin air.

But the “Do Real Planning” checklist was not intended to substitute for revising our community plans. We have to revise our community plans. When the city finally implements a policy of updating community plans on a continuous basis, that will be when we have truly arrived at “Do Real Planning.”

Michael Woo: Commissioner Donovan, you are the only person on the panel who currently holds a position in the city government. Are the problems that were cited by the judge in the Hollywood Community Plan unique to Hollywood? Or are there lessons that are applicable to the Westside and other community plans in Los Angeles?

Tom Donovan: Community plans are kind of like the stepchild of planning. Planners don’t like having to do them, but they must. Cities don’t like following them. We do the community plan, put it in a drawer, and never really look at it again.

Michael Woo: You seem to be saying that on balance you are better off reading what’s in the community plan than not reading what’s in the community plan

Tom Donovan: It’s supposed to be a constitution for planning in this city.

Michael Woo: I can’t resist adding a personal note. When I was in graduate school in city planning, one of my mentors was Professor T.J. Kent Jr., the author of a book called The Urban General Plan, which for many years was considered the textbook for general plans and community plans. And even though I was a native of Los Angeles and he was a die-hard Bay Area native, we got along well because we were both interested in the connection between planning and politics.

Kent had been planning director of San Francisco and a Berkeley city councilman. But he was always a little bit suspicious of me being from Los Angeles because he felt that there was something different about Los Angeles that made it difficult for the concept of a community plan to apply. Unlike the Bay Area, he felt there was something weird about LA that had something to do with the scale, the sheer size of the city and the region, and the lack of a civic culture that would support real planning.

Let me ask this follow up question to Dale Goldsmith. Why is it that other cities in Southern California such as Santa Monica and Pasadena have been able to keep their general plans up to date, and yet the City of Los Angeles doesn’t seem to have the political will to do this? Why is that?

Dale Goldsmith: It is certainly a question of political will. If the city council was really focused on getting the plans up to date, I think you’d see a lot more progress. But keep in mind that Los Angeles is a vast city. Mike, when you were a city councilmember you had more constituents than a Senator in Wyoming. And you have huge geographic variation, even with some of the 35 community plans. Hollywood, for example, has hillsides, dense urban areas, and ethnic neighborhoods—I think that makes the planning process a lot more difficult. I agree with your professor that LA is different and harder because of the scale. Size does matter in planning.

Michael Woo: Let me ask you a follow up question. One theory about the Hollywood Community Plan case is that the outcome won’t really affect big developers. The presumption is that big developers can afford to pay for the costs of going through the process, so the bigger impact will be on small and medium sized developers and property owners. What do you think is the real impact of what happened in the Hollywood Community plan relating to developers and development?

Dale Goldsmith: You’re right with respect to big developers. I’ve been involved in a number of large projects in Hollywood, and if you prepare to go through the long, arduous process with a good lawyer, a good EIR consultant, and a good community relations consultant, you can probably get it done.

When I was doing the Hollywood and Vine project, it was a successful project, but it was a multi-year process, and millions of dollars were spent. The big projects can afford that, but the medium and little projects might not, having to go through a general plan amendment and zone change—and that’s really what we’re talking about—to change those now stale pieces embedded in the old plan. It’s a long and arduous process.

In Hollywood, where litigation is prevalent, you always have to do an EIR. So a project that might pencil with a shorter and more administrative process might flounder on the lengthy general plan.

Michael Woo: You’re saying that your business as a real estate attorney benefits from a system, which places greater emphasis on discretionary decisions rather than by-right decisions in the planning process?

Dale Goldsmith: Well, I never put my own pecuniary interests ahead of good planning.

Jane Usher: If you read a handful of community plans, you will see they are all predicated on the same language. They have the same passages verbatim, and each plan reads like its neighboring plan. One of the things Gail Goldberg talked about was the idea that our community plans in the update process would be individualized and unique to the neighborhood. They would anticipate infrastructure, schools, churches, fire, and police.

So as we continue the conversation, arriving at that kind of community plan will be distinct from what we already have.

Michael Woo: Can you give us any insight into the city’s legal strategy in the case of the Hollywood Community Plan? Was the City Attorney’s office aware of the vulnerability of the population growth projections?

Jane Usher: There is very little in this question that I can answer since I have a duty of confidentiality to my client, the City of Los Angeles. But let me say, without breaching that duty, that I think all of city hall was aware of the vulnerabilities of the Hollywood Community Plan. A publicly known debate was occurring in city hall in every office. It pains me a little bit that the judge issued his verdict and everyone assumes city hall was clueless. Ladies and gentlemen, they were not.

But we talked about this culture where everyone from the planners, the city attorneys, and building and safety operates. This culture includes timelines and considerations beyond those that the law requires. So it’s always a balance and navigation.

The lesson the judge delivered is one the courts have issued to Los Angeles a number of times. It’s the same message—the City of Los Angeles, in your land use and environmental decisions, we the judiciary need to see the logic that you’ve followed. We want you to connect the dots for us. Bridge the analytical gap.

So the courts have told the City of Los Angeles that this is what they want us to do as a city. They want us to give them the facts and then connect the dots for the courts and public to see how we arrived at our decision. And I think that’s incredibly reasonable.

Dale Goldsmith: I would like to follow up on the legal strategy. There’s not really a ton of strategy by the time the case comes to you. In a written mandate action the decision is highly based on the administrative record.

The issue I have is that the Planning Department brought a bread knife to a gun battle. Hollywood is a notoriously difficult place to do business. It reminds me of the line from Chinatown, “Jake, it’s Chinatown!” Well, I’d say, “Jake, it’s Hollywood!” I’ve had about a 90 percent litigation rate of the projects I’ve gotten involved with in Hollywood. It’s a very litigious area. Some people are doing it for environmental outsourcing, but I’m not convinced that everybody has that same motivation. At the end of the day I think you need to assume you are going to get sued and make sure that the record is prepared robustly accordingly.

This means several things, one of which is that due to budgetary limitations the City Attorney’s office is not involved at day one. If I were to represent a client and then just show up at the end, I would be committing malpractice. The City Attorney’s office has so many responsibilities, but if they could get involved earlier on, then the records would be better and the planners would have appropriate legal advice.

In addition, it took a very long time to get the Hollywood Community Plan done. They say that time kills all deals, and I think it killed this one. If the EIR document had been certified before the new census data came out, we wouldn’t be having this discussion right now. The City Council really controls all this stuff, and with the will and resources it could be done a lot faster, and you won’t have these issues of time making your EIR stale.

- Log in to post comments