Facing an August 30 deadline, the California Assembly Appropriations Committee is set to hear Sen. Nancy Skinner’s SB 330, "The Housing Crisis Act of 2019," a controversial proposal to preempt local planning and zoning processes and significantly limit public engagement in development decisions. In continuation of TPR's ongoing coverage of state legislative efforts to wrest planning and zoning control from local governments, republished here with permission is the Embarcadero Institute’s plain-language analysis of the on-the-ground impacts of the bill. Citing SB 330’s lack of affordable housing provisions, the report offers recommendations for streamlining affordable housing without stifling community engagement or imposing one-size-fits-all development review processes. Find Embarcadero Institute’s original report and more resources on local policy impacts here.

Nancy Skinner

"SB 330 is a statewide bill intended to reduce the time it takes to approve housing developments in California... would take away significant authority from cities and counties, reducing their review and approval powers over developments that shape their communities … A better provision would help facilitate and streamline rezoning requests for affordable housing developments"

Overview

Senate Bill 330 “The Housing Crisis Act of 2019” is a statewide bill intended to reduce the time it takes to approve housing developments in California. Under state law, “housing developments” include residential units, mixed-use with a large residential component, and transitional or supportive housing.

The bill is complex and is bound to other laws including the Housing Density Bonus Law. SB 330 would take away significant authority from cities and counties, reducing their review and approval powers over developments that shape their communities.

This shift is reinforced in three ways: itfreezes the ability of local governments to downzone, adopt new development standards, or change land-use in residential and mixed-use areas if the change results in less-intensive uses; it allows developers to request approval of housing developments that exceed density and design controls of the underlying zoning, if the existing zoning is in conflict with the General Plan or a Specific Plan; and itexpedites the permitting process for all housing development and limits the list of application materials that cities can review.

Implications

SB 330 would affect all cities in California and place extra restrictions on “affected cities and counties.”It may expose some municipalities to a barrage of appeals and lawsuits, yet it contains no apparent effort to address the housing affordability crisis.

The bill limits a city’s or county’s ability to adopt zoning that reduces residential density, or to impose design standards that limit the housing units allowed. Any such zoning changes made by a city after January 1, 2020, in residential or mixed-use areas, would be preempted.

It further preempts local zoning if in conflict with a General Plan or the land-use element of a Specific Plan, allowing proposed housing developments to override local zoning. This could expose cities to housing development proposals that do not comply with adopted zoning standards such as density, size and design criteria. This could create confusion and expose cities to legal challenges over which standards apply, bogging down the review process and achieving the opposite of what the bill intends.

SB 330 limits public hearings to five, reduces the criteria against which a municipality can review in a development application, and restricts the timeline during which a denial can be issued. To comply with this limitation, some cities could change which public bodies hear development cases, reserving hearings to primary approval bodies such as city councils and planning commissions, and limiting community-based hearings held by entities such as historic preservation boards or neighborhood review committees. This could minimize the voices of the least powerful as community-based hearings designed to build consensus or support are disincentivized.

Property owners, as well as potential future residents and “housing organizations” can appeal or bring a lawsuit if a municipality doesn’t follow the state mandated process. Giving legal standing to parties with no established property interest (and who may have competing interests), could expose local governments to lawsuits and appeals by multiple parties, creating further delays rather than streamlining the process.

Finally, the bill limits cities’ and counties’ ability to charge application and impact fees. Local governments may still charge for application review and fees to offset increased road usage, public safety needs or other services — but only annual increases following automatic adjustments based on a cost index.

“Affected Cities and Counties”

In addition, nearly 450 cities and unincorporated parts of counties would be classified as “affected” and face further restrictions on their review authority over proposed housing developments. SB 330 prohibits moratoriums on residential and mixed-use projects in “affected” cities and counties. For example, a developer could present a mixed-use office project, and the “affected” city would have to process it — even if the city limited new office or commercial development in certain locations. The bill also freezes a municipality’s ability to change zoning and design standards that downzone or limit housing development. In order to downzone a property, affected cities and counties must demonstrate how the “net amount” of housing units will not decrease city- or county-wide. However, tracking the number of “net” housing units is open to interpretation, fueling possible disputes.

Development Process Changes Under SB 330

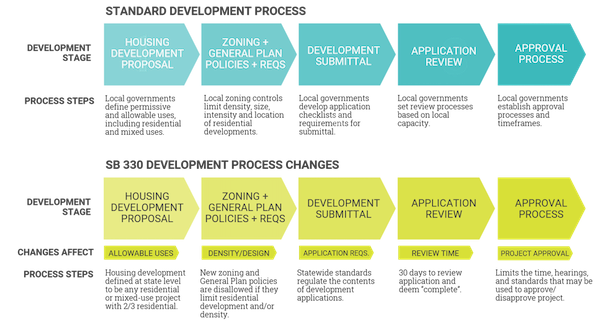

In some cities and counties, the changes proposed may have little impact. In others, the impact of the changes may more extensive. A simplified comparison of the development review process currently and under SB 330 is shown below, which illustrates some of the implications if SB 330 is approved. This graphic shows how the statewide standards in SB 330 affect a typical, simplified development process from proposal to approval.

Embarcadero Institute Recommendations

If the goal of SB 330 is to streamline the development of housing in California, the bill should target local practices that limit housing development (especially affordable housing), instead of taking a one-size-fits-all approach to application requirements and procedures. Although standardized, and in some cases simplified, application processes could help some cities, these recommendations should be implemented as statewide best practices, not as mandatory process requirements.

A few changes that could help SB 330 meet its stated goals including redefining “housing development” more narrowly to include only multifamily housing developments and mixed-use developments with residential as the primary use (e.g. limiting commercial elements to ground-floor neighborhood commercial uses); removing language allowing informal rezoning, or the application of General Plan land use designations that supersede zoning requirements (General Plan land-use policies should not supersede local land-use code when the two are in conflict); removing the January 2018 retroactive freezes on downzoning and code changes, making the freezes effective the date of SB 330’s passage; and narrowing the focus of streamlining efforts to affordable housing developments, as defined in other statutes. The bill, as written, could incentivize market-rate housing development, while affordable housing is the primary housing need. A better provision would help facilitate and streamline rezoning requests for affordable housing developments.

- Log in to post comments