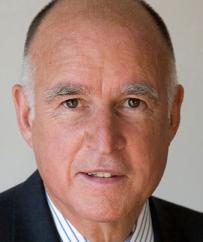

The following excerpts are from a recent event held at UCLA entitled the Governor’s Conference on Local Renewable Energy Resources. The “Governor’s Panel,” excerpted here by MIR, kicked off the event with panel facilitator Steve Clemons, Washington editor at large of the Atlantic Monthly, and panel participants that included Gov. Jerry Brown; David Crane, CEO of NRG Energy; Lyndon Rive, CEO of SolarCity; and Rick Needham, director of green business operations and strategy for Google. Gov. Brown had perhaps the most provocative statement of the panel’s proceedings: that those opposing to the development of renewable energy should be ‘crushed.’

"In Oakland, I learned that you have to crush some kinds of opposition. You can talk a little bit, but at the end of the day you have to move forward. California needs to move forward with renewable energy..."

Steve Clemons: Governor Brown, how did things look 30 years ago when you started looking at oil dependency and moving into renewables. How comparable was then to now, when we’re actually doing it?

Gov. Jerry Brown: In the early ‘70s the projection was about 7 percent annual increase in energy consumption. A fellow named Amory Lovins wrote an article in Foreign Affairs where he flattened that curve dramatically and said, “It’s not needed.” That was heresy at the time.

Renewables at that time were mostly solar hot water, and then the emergence of wind power. Of course wind power raised the specter of Don Quixote. I pushed ahead with wind, although wind and woodchips became a kind of slogan there, which wasn’t favorable. Renewables seemed far more marginal 30 years ago.

What I’ve begun at Blythe this year, with the dedication of a 1,000-megawatt set of solar power plants, is a $5 billion investment in the sand. The fellow who is heading up the company ran automobile factories in Europe. He said this is all off-the-shelf technology. He has to build a whole assembly line, literally in the sand in Blythe, California, which is pretty far out from civilization. That’s practical. That’s real. It has happened.

In terms of wind power, California in the mid-80s had 94 percent of the electricity generated by wind. It was only about 1,800 megawatts, but it was 94 percent of the world’s wind. This is just what we’ve done. Photovoltaics were a lot more expensive then. It was inconceivable that what we’re talking about today would be possible. Of course there is also the great opportunity to boost energy efficiency. I can remember the Energy Commission set that up and the developments fought it like crazy, that this would be another burdensome regulation. That’s the way it was perceived. But we pushed it through.

It was the same story with appliance standards to make refrigerators and other appliances more efficient. We got that lined up and then the national administration under president Reagan preempted California on appliance standards and adopted a “no-standard standard.” That set us back. Then the price of oil came down, and pretty soon everybody was taking a step back.

Now we have a maturing, still by no means mature, but compared to what it was then, a much more mature and very real sector. It is just beginning. I even remember when the Apple 2 was a very bold little instrument. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak supposedly created it in their back yard in 1973. It’s hard to remember but there was no personal computer in the 70s. So it can move very, very quickly. The microchip was invented in the 60s by a guy named Robert Noyce. It came right out of Palo Alto. We’re in that early stage.

Energy is a huge part of a live economy and the sun is abundant power. All we have to do is capture it. There are technical problems, there are financial problems, there are regulatory problems, and there are coordination problems. I can tell you that the various agencies in California—ISO, the PUC and the Energy Commission—are working together. My office is actively involved when local communities try to block the installation of photovoltaic, like some folks did in San Luis Obispo. We act to overcome the opposition.

In Oakland, I learned that you have to crush some kinds of opposition. You can talk a little bit, but at the end of the day you have to move forward. California needs to move forward with renewable energy, and I’m going to everything I can to bring together and to keep working with all those different agencies. This is a hard time for government. There is nothing more powerful than turf, and each department has it’s own turf. You need a superior authority to blend all those turf divisions together. I can assure you that you are going to get a very active involvement from the Executive Branch in the state of California. We’re going to get this done because this is the next oil industry or the next computer industry. It’s not going to happen overnight, but we’re on our way, and what we do over the next couple of days will be a very important step forward.

Clemons: Let me turn to David Crane. David, you’re out of Texas. You look at this broad, distributed generation question. You have a holistic view of what can be achieved here with NRG Energy that is somewhat revolutionary. Can you walk us through a few of the investments? You’re making major investments in California across a number of major projects. But you’re also looking at the distributed generation question very seriously.

David Crane: First, we applaud the governor in his 12,000 megawatt goal. Distributed generation is the cutting edge of that holistic view that you’re talking about. That is the way that we would look at it. We’re doing a lot of the utility side solar as well. Maybe not 1,000 megawatt projects, but ultimately several 100-megawatt projects out in the California desert. That’s very positive.

We have to recognize that the 12,000 megawatt distributed generation goal has to be consumer-driven. Someone has to buy those 12,000 megawatts. You can’t exercise leadership if people aren’t paying attention. The average American spends 2.4 percent of their disposable income on electricity. They spend twice that to fuel their car. Most Americans are much more used to thinking about energy in the context of cars.

One thing that could be very helpful, because California is the leader in electric vehicles and distributed generation, is a way to incentivize businesses that tie those two together. This is very uncharacteristic, but in a lot of ways, big business is ahead of the average American when it comes to understanding why we need to be sustainable. Ninety-three percent of major multinational corporations say that they want sustainability to be a fundamental part of the image they present to the American consumer. Anything that can enable businesses is how you get businesses to pay attention and synthesize things like distributed generation, particularly rooftop distributed generation. Then you don’t have some of the noise about using land, which is a scare commodity.

Rooftops are generally a non-controversial place to put distributed solar. How do you get businesses to read and then synthesize distributed generation, distributed solar, and electric vehicles with smart meters to create the holistic solution you’re talking about? Ultimately what we’re talking about here: we’re trying to point our company at the democratization of energy.

The energy industry has to get where communications and IT got 30 or 40 years ago. It’s about individuals having choice and controlling their own energy destiny. That’s putting all these things together. Distributed solar is the start.

Clemons: If we were in Washington, and I had the staff directors of the Republican and Democratic senators on the Energy Committee, who I met a couple of weeks ago, they’d tell you they think that the solar and energy area has the most “promise.” They don’t look at it in the way that this room does—that this is an immediately viable option across communities. That you’ve got real goals set, that you’re looking at communities, permitting processes, and levels of major investment. Washington, at least, thinks there is a scalability problem. Your company plays across a number of energy platforms. Is that an unfounded view from D.C., or is there credibility to that?

Crane: There is no credibility in Washington. At this point, I wouldn’t count on Washington for anything. California is a big place. The scale that the governor is talking about is huge. That will create an industry for the whole country right here in California. California can lead that wave. Texas can lead that wave. Just a few states can lead that wave. Most of the country is very interested in solar.

I live in New Jersey, and that interest is true in the Northeast states, where there is less sun. But I have to tell you, the other day I was at this little event and the Governor of Texas was standing there, and someone said, “I want you to meet the governor of Virginia,” who was standing next to the governor of Texas. He started to talk about how on the East Coast, they are very excited about offshore wind. You don’t hear that out here because you don’t have the right continental shelf. But the governor of Virginia started talking about all the things he wanted to do to incentivize offshore wind. He said that with the Governor of Texas, who is obviously an extremely conservative human being, sitting right next to him. I whispered to him, “Governor, are you a Republican?” He said “Yes, I’m a Republican. That’s why I’m standing here with the Governor of Texas.” But that is the nature of being a governor. Governors are trying to get things done. They’re trying to create jobs and build our economy, and it doesn’t really matter whether they are Democrats or Republicans. They are all trying to be practical. That is completely opposite from what we’re seeing in Washington. As we go around the country, we’re much more focused on what’s being done at the state level, because there doesn’t seem to be anything that can be done at the federal level.

Clemons: Rick, Google is not an energy company. It’s an energy user. But as you’ve stated dozens of times, Google looks at the energy question in the state, the nation, and around the world as a vital issue for the firm. Why is Google putting such big stakes of your portfolio in this area?

Rick Needham: First, I’d like to also congratulate the governor on being a leader in signing the most aggressive renewable portfolio standard in the country. The short answer to your question is that renewable energy and sustainability are great business opportunities. We believe that this is an industry where if we fail to invest, we will lose those opportunities.

We often get asked the question, “What is Google doing in the renewable energy space?” The answer is pretty simple. Like other companies, energy drives our business. As a company that has sustainability as a core value, we want to make sure that we use energy as efficiently and get our energy from sources that are as clean as possible. We’ve done several things to make that happen. First off is, as Amory Lovins would point out, the first thing you can do is just reduce the energy that you’re using. We spent a lot of time and effort doing that, by having data centers that use half the energy that a standard data center uses in the industry today.

Beyond that, we have focused on sourcing renewable energy. When we made a commitment to be carbon neutral back in 2007, there weren’t a lot of great options for renewable energy. We decided to do what we could to help support those options. We’ve done things like make investments in early-stage companies. We have our own R&D, we’ve made investments in large-scale renewable energy projects, and we’ve put facilities for power generation on-site at our corporate campus, including solar and fuel cells.

We’ve committed over $780 million to renewables. That’s just the projects. Over half of that will be for projects in the state of California. California is leading, and that allows investors like us to say that these projects make great business sense for us. They also help to move California to a cleaner economy, and they are great business opportunities for California to maintain that leadership. Those projects will also generate about 1,500 megawatts of clean power into California, so we’re very excited about that.

We’re just one company. We’re doing what we can to help usher in the clean energy future, which we think is important and a good business opportunity. But we recognize that we’re one company. We encourage other private institutions, other companies, to do what they can to help support renewable energy within their own business models. We’ve found project investments that make sense for us on a returns basis, looking at the risks, and help push forward the industry and technologies that will get us there. We would encourage other companies to do the same. Take a look.

There are other opportunities to invest here. As people have pointed out already, financing is one of the key constraints. We’re helping to do what we can to help relieve that constraint, which still needs relief. We would encourage other investors, who maybe aren’t in the space, like you would say we’re not, to look. There are opportunities there to make good returns and to help diversify your cash holdings while promoting an industry that makes a difference.

Clemons: Governor Brown, has your office been working to promote cookie-cutter approaches to expedite consistent ordinances and regulations for solar installation?

Gov. Brown: There is permitting per house, and there’s permitting for larger five or ten megawatt photovoltaic installations on business rooftops. There are two regulatory hurdles. The first is getting a permit. To do any work on your house over a minor dollar amount you’re supposed to get a permit. That could take a cookie-cutter approach. We could also bring pressure to bear. There are 58 counties and over 400 cities in California. They could all issue these permits.

Then we have another issue, where the environmental review, planning department, or planning commission discussion and decisions invite community participation and nurture opposition and slow everything down. We have 38 million people, and with all the subsets of that 38 million, there is always going to be somebody who says “no.” They reject change because change is different, and some people don’t like the difference.

Our system of participation is such that any old fool could obstruct anything. So what’s the way forward? Restricting participation is very difficult. It has the feel of being undemocratic. Yet if you allow every person, however benighted, to play a role, you won’t get anything done. That’s why I mention my experience in Oakland. You have to push in a certain way that almost feels arbitrary. But the way our system has evolved, with tens of thousands of laws and hundreds of thousands of regulations, it is very hard for anyone to make a decision quickly. I know people rail against the regulations and say, “Let’s just change it.” Regulations are so embedded into our culture and our legal system that it is difficult to overcome them. It’s a product of the state of where we are in our current history and development.

I believe things can be done. That’s really what I’m looking forward to as one of my prime responsibilities—overcoming inertia at the local level. What you’re overcoming here is logic: every law has a certain logic that continues to expand its reach. The only way to stop that is to intervene. That’s what this takes. If we just sit around and watch the process unfold, we’re not going to get to the goal in the timely way that we should. That’s the commitment that I’m going to make, and I know everyone here has a role to play.

Locally, this is not going to be about the Energy Commission. This is going to be about county boards of supervisors. This is going to be about city councils. This is going to be about planning departments. This is going to be one person inside a planning department in some small city somewhere. That’s a lot of distributed power—political power. We need a centralized base of arbitrary intervention to overcome the distributed political power that is blocking forward progress.

Clemons: Lyndon, do you want to jump in with a little bit of your experience? The United States is right now is, I think, 27th in the world compared to other countries in terms of the ease of getting permits and doing business. Not so good. It would be interesting within California to look at communities that get it and those communities that don’t. I don’t know if your company wants to do that. It might put you in the bull’s eye. But it would be interesting.

Lyndon Rive: That sounds like a project for the industry association. I know there is a lot of emphasis on this. But if we’re ranking barriers, the number one barrier is education. Educating the market is still the hardest challenge that we as a company face. The biggest barrier is education. People still say, “But does it really work?” after you’ve explained it. They don’t understand what solar electricity is. After you spend ten minutes explaining that you can finance it instead of paying for it, that they will get the set for free and only pay for the power, at the end of the conversation they say, “How much does it cost to get it installed?” What the CSI program has done has evolved business models. The barrier is educating the market that solar is real and it’s a viable solution for energy, and a good investment for consumers and businesses.

Clemons: I’d like pose a question to the panel and Governor Brown on a serious issue that we worry about in Washington: jobs. We hear a lot about green energy jobs. If you look at the last decade, green energy jobs have grown about two and a half times faster than other jobs. It’s very hard for me to imagine a greater concentration of renewable expertise and real market power than exists in this room right now. If we were to go to the equivalent in Germany or China, we might be dwarfed because they have done so much in terms of laying out and subsidizing. The New America Foundation, which I helped found in Washington, did a study of research dollars. For every dollar that goes into the research and development side of renewables, about three quarters of it goes immediately to China, Germany and Scandinavia. It looks like there is an absence of what we used to call industrial policy (i.e., connecting demand and targets to build capacity). Lyndon, you’re out on the retail side hiring people. How would any real advances in this would change the job equation in this state and perhaps nationally?

Rive: One of the things about the distributed generation (DG) job creation is that whenever you get an industry, you often get it concentrated in a core region. Technology, for example, is core in Northern California, and the film industry in Southern California. But for DG, the core essentially spreads out. There are local jobs in every community. I know there is a lot of emphasis on jobs being exported to China and the power of manufacturing. But most of the jobs are often created in delivery. In my experience, delivery is about two or three times more than the manufacturing. You cannot outsource delivery. Delivery has to be local.

Crane: I agree. The clean tech industry is creating jobs. It’s just that the American public doesn’t see it. The political opposition is saying that by raising the price of electricity, you’re going to destroy more jobs than you directly create, which is an unproven concept. That’s a big advantage of distributed solar over utility-sized solar. When you build a 300-megawatt solar or photovoltaic out in the desert, no one will see the jobs created. But when you’re doing distributed solar in neighborhoods, local people install them. There job creation diversifies, with much more visible job creation. That’s a very positive aspect of DG.

Needham: The cost of panels has seen dramatic reductions over the last few years. Even over the last two years, the cost of energy from solar panels has dropped by around 34 percent. They are on an incredible cost reduction curve, which is a great opportunity to deploy these panels with business models that, frankly, make a lot of sense. Unless they didn’t understand the business model, who wouldn’t sign up to have solar power on their roof, lowering their cost of energy? That sounds like it makes sense to me. That kind of a business model will distribute solar rollout a lot more broadly. The thing about clean energy jobs is that if we don’t take a leadership position, those jobs just won’t happen. California’s leadership role is very important, especially on the distributed generation side, because that’s where the bulk of the jobs will come from. We’re very supportive of those kinds of business models, and we’ll continue to look at opportunities to invest in the state.

Gov. Brown: If we were in Germany or China, there would be a lot more people talking about distributed energy. There would be more people and more eyes on the prize. That’s because those two counties have systems that allow executive leadership more latitude. For whatever historical reasons, particularly in California, a system has evolved that constrains leadership at all levels in the public sector. There are so many people who can block things. When we are in the position of deficit revenue people fight over less. They are fighting over whatever they can get or grab or persuade some people to vote them. That is the existing power base. That is the existing power. Not electrical power or solar power, but the interest groups that have historically been at the government revenue stream. That’s where all the action is.

If you read what’s going in Washington, they are not about distributed solar power. They are talking about the debt limit. They are talking about revenue or not revenue. They are talking about cutting entitlements. That can occupy a lot of intellectual and political energy. The task of maintaining the country and the our historical momentum is that somebody has to think long term. That somebody has to have some authority, and they have to exercise it. Yet in some ways, it has become almost un-American to vest any political personality with enough authority to get stuff done that doesn’t please the immediate news cycle. That is really the challenge we’re facing.

Can anybody anywhere in the public sector make long-term decisions and make them stick? In California we have the Public Utilities Commission. It only takes three votes to get a decision. Before you get the three votes, you have to have endless interveners and filings to talk about it. At the end of the day, it’s still only three out of five. It’s a lot less than 41 in the assembly or 21 in the senate. Now of course, if the PUC gets rates going up too high, then I’ll have to throw out the people I appointed to it. There are constraints.

There are two issues. One, nobody is in charge, and anybody who gets in charge gets pulled back pretty quickly. Two, long range thinking, when it takes immediate cost, is not privileged and is not favored. I’ll give you an example, the Pace program. The Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) program to me is a no-brainer, where lenders can enable homeowners to put a lien on their house as collateral for a loan for renewable energy. Now, why did the federal government, in a progressive administration, stop that? It’s long term: we’re afraid from yesterday’s meltdown in the financial markets. So, no PACE program. Even though 25 states have adopted it, the federal government has killed it. It doesn’t make much sense, but it’s an example of the very opposite of long-range thinking to deal with issues.

If all we do is fight over the problems and the deficits and we don’t make long-term investments, then America will be in deep trouble. It takes executive leadership and long-range planning.

Clemons: You just came up with a concrete example of how Washington got in the way of long-term planning and the welfare of its citizens. It contracted the financial and economic horizon for them. Are their other things in this energy environment that D.C. does that put up more hurdles than help?

Gov. Brown: I’m sure they do, and many years ago I could probably think of them. It’s not just enough not to put the hurdles up though. That’s a very low bar. What about doing things? What about getting stuff done? One thing you have to recognize is that the stimulus program that President Obama and Congress put together is the biggest energy investment program America has ever had. That was a big, big win. And that’s when we had a big bucket of money in response to this fiscal crisis. So what are the ingredients of that? The ingredient is massive fear that the financial system will collapse. Therefore, give me $750 billion, and I’ll fix it. However, you can’t get that very often. How do we get $750 billion without a financial panic? That’s the real problem. How do we get people to invest and spend? That’s the dilemma of where we are right now.

- Log in to post comments