On April 8th Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and the USC Schwarzenegger Institute in partnership with the USC Center for Sustainable Cities are holding a public comment forum on the National Climate Assessment and Development Advisory Committee’s Draft Climate Assessment Report on the Southwest Region. MIR has excerpted part of the report focusing on the American Southwest, already the hottest and driest region in the United States, and what the region may expect as global temperatures increase. The goal of program is to garner comments and feedback that will be forwarded to program’s advisory committee.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger

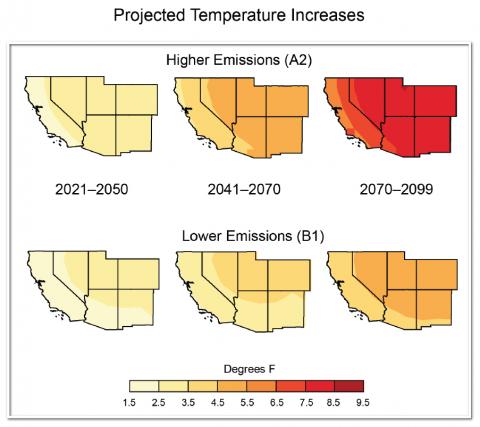

"Regional annual average temperatures are projected to rise by 2°F to 6°F by 2041-2070 if global emissions are substantially reduced (as in the B1 emission scenario) and by 5°F to 9°F by 2070-2099 with continued growth in global emissions (A2), with the greatest increases in the summer and fall."

Daniel A. Mazmanian, Professor of Public Policy at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy provided MIR with several questions through which this draft report may be understood by members of the Los Angeles planning and business communities:

• Should we be preparing for sea-level rise in Los Angeles? What are the prospects and how high will it rise according to the leading researchers in the nation and region?

• Should we be preparing for sea-level rise in Los Angeles? What are the prospects and how high will it rise according to the leading researchers in the nation and region?

• Does the melting of the Sierra Snow Pack mean we will have to find water for our homes, industry, lawns, and gardens elsewhere? What will it mean for California agriculture, which has been the breadbasket of the nation for the last half a century?

ª What steps should be taken today to prepare for the highly likely but never certain future effects of climate change?

Introduction

The Southwest is the hottest and driest region in the US, where the availability of water has defined its landscape, history of human settlement, and modern economy. Climate changes pose challenges for an already parched region that is expected to get hotter and, in its southern half, significantly drier. Increased heat and changes to rain and snowpack will send ripple effects throughout the region’s critical agriculture sector, affecting the lives and economies of 56 million people—a population that is expected to increase by 38 million by 2050. Severe and sustained drought will stress water sources already over-utilized in many areas, forcing increasing competition among farmers, urban dwellers, and the region’s varied plant and animal life for the region’s most precious resource.

The region’s populous coastal cities face rising sea levels, extreme high tides, and storm surges, which pose particular risks to highways, bridges, power plants, and sewage treatment plants. Climate challenges also increase risks to critical port cities, which handle half of the nation’s incoming shipping containers.

Agriculture, a mainstay of the regional and national economies, faces uncertainty and change. The Southwest produces more than half of the nation’s high-value specialty crops, such as vegetables, fruits, and nuts. The severity of future impacts will depend upon the complex interaction of pests, water supply, reduced chilling periods, and more rapid changes in the seasonal timing of crop development due to projected warming and extreme events.

Climate changes will increase stress on the region’s rich diversity of plant and animal species. Widespread tree death and fires, which already have caused billions of dollars in economic losses, are projected to increase, forcing wholesale changes to forest types, landscapes, and the communities that depend on them.

Tourism and recreation, generated by the Southwest’s winding canyons, snow-capped peaks, and Pacific Ocean beaches, provide a significant economic force that also faces climate change challenges. The recreational economic will be increasingly affected by reduced streamflow and a shorter snow season, influencing everything from the ski industry to lake and river recreation.

Observed and Projected Climate Change

The Southwest is already experiencing the impacts of climate change. The region has heated up markedly in recent decades, and the period since 1950 has been hotter than any comparably long period in the last 600 years. The decade 2001-2010 was the warmest in the 110-year instrumental record, with temperatures almost 2°F higher than historic averages, with fewer cold snaps and more heat waves. Compared to temperature, precipitation trends vary considerable across the region, with portions experiencing both decreases and increases. There is mounting evidence that the combination of human-caused temperature increases and recent drought has influenced widespread tree mortality, increased fire occurrence and area burned, and forest insect outbreaks. Human-caused temperature increases and drought have also caused earlier spring snowmelt and shifted runoff to earlier in the year.

Regional annual average temperatures are projected to rise by 2°F to 6°F by 2041-2070 if global emissions are substantially reduced (as in the B1 emission scenario) and by 5°F to 9°F by 2070-2099 with continued growth in global emissions (A2), with the greatest increases in the summer and fall. Summertime heat waves are projected to become longer and hotter, whereas the trend of decreasing wintertime cold snaps is projected to continue. These changes will directly affect urban public health through increased risk of heat stress, and urban infrastructure through increased risk of disruptions to electric power generation. Rising temperatures also have direct impacts on crop yields and productivity of key regional crops, such as fruit trees.

Projections for precipitation changes are less certain than those for temperature. Under a high emissions scenario (A2), reduced precipitation is consistently projected for the southern part of the Southwest by 2100, but there is model disagreement on the direction of change in the northern part of the region. Seasonally, significant decreases in spring precipitation in the south are projected, which a mix of increases and decreases are projected for the other seasons and in the north. An increase in winter flood hazard risk is projected due to increases in flows of airborne moisture into California’s coastal ranges and the Sierra Nevada. These “atmospheric rivers” have contributed to the largest floods in California history, and can penetrate inland as far as Utah and New Mexico.

Projections for precipitation changes are less certain than those for temperature. Under a high emissions scenario (A2), reduced precipitation is consistently projected for the southern part of the Southwest by 2100, but there is model disagreement on the direction of change in the northern part of the region. Seasonally, significant decreases in spring precipitation in the south are projected, which a mix of increases and decreases are projected for the other seasons and in the north. An increase in winter flood hazard risk is projected due to increases in flows of airborne moisture into California’s coastal ranges and the Sierra Nevada. These “atmospheric rivers” have contributed to the largest floods in California history, and can penetrate inland as far as Utah and New Mexico.

The region has experienced severe, 50-year-long mega-droughts over the past 2000 years. Future droughts are projected to be substantially hotter, and for major river basins, such as the Colorado River Basin, drought is projected to become more frequent, intense, and longer lasting than in the historical record. These drought conditions present a huge challenge for regional management of water resources and natural hazards like wildfire. In light of climate change and water resources treaties with Mexico, discussions are underway, and will need to continue into the future, to address demand pressures and vulnerabilities of groundwater and surface water systems that are shared along the border.

- Log in to post comments