In August, law firm Holland & Knight released the first comprehensive study of lawsuits filed under the California Environmental Quality Act, titled “In The Name of the Environment.” Here, report co-author and Holland & Knight partner Jennifer Hernandez summarizes the findings for TPR. Given that the study identified widespread litigation abuse, Hernandez proposes three moderate reforms to help curtail these practices. Click here for a copy of the complete report.

Jennifer Hernandez

“CEQA litigation is not a battle between ‘business’ and ‘enviros’—49 percent of all CEQA lawsuits target taxpayer-funded projects with no business or other private sector sponsors.” —Jennifer Hernandez

In honor of my father and the million other Californians who lost manufacturing jobs in California’s steadily eroding middle class over the past decades, and in recognition of the nine million Californians who the US Census Bureau found live in poverty (making our state home to the highest number of poor and the highest poverty rate in the United States), I and other members of our law firm recently completed a comprehensive study of all lawsuits filed statewide under the California Environmental Quality Act over a three-year period (2010-2012). The report’s goal was to get past anecdotes and divisive rhetoric, and document the widespread non-environmental litigation abuse of CEQA which we believe undermine the state’s environmental, climate, social equity and economic priorities. Among the study’s key findings:

• CEQA litigation is not a battle between “business” and “enviros”—49 percent of all CEQA lawsuits target taxpayer-funded projects with no business or other private sector sponsors.

• Projects designed to advance California’s environmental policy objectives are the most frequent targets of CEQA lawsuits: transit is the most frequently challenged type of infrastructure project (edging out challenges to both highways and local roadways); renewable energy is the most frequently challenged type of industrial/utility project; and housing (especially higher-density housing) is the most frequently challenged type of private-sector project.

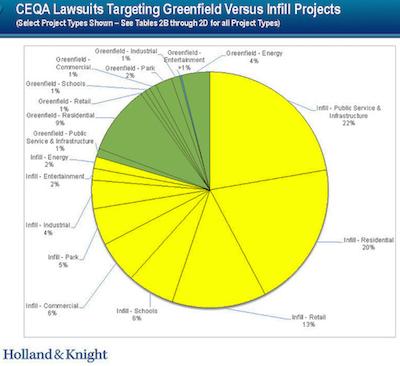

• Debunking claims by special interests that CEQA combats sprawl, the study shows that projects in infill locations—in our existing communities—are the overwhelming target of CEQA lawsuits. For challenged agency approvals that have a clear physical location (e.g., a construction project rather than a statewide regulation), 80 percent are in infill locations and only 20 percent are in “greenfield” exurban and rural locations. These lawsuits were aimed at the full range of core urban services, including schools, parks, and infrastructure, as well as projects creating new housing units (most often multi-family and attached homes) and new jobs in offices and retail stores that involve no hazardous chemicals or industrial pollution sources.

• 64 percent of those filing CEQA lawsuits are individuals or local “associations,” the vast majority of which have no prior track record of environmental advocacy. CEQA litigation abuse is primarily the domain of Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) opponents and special interests such as competitors and labor unions seeking non-environmental outcomes. Only 13 percent of CEQA lawsuits were filed by groups with a track record of prior environmental advocacy, such as the Sierra Club and more local organizations like SCOPE and EPIC.

I believe that ending CEQA litigation abuse is the most cost-effective way to restore the state’s middle-class job base, make housing more affordable, ensure that taxpayer funds on critical infrastructure needs like transportation are spent on projects instead of endless process, and improve the future of the nearly nine million Californians living in poverty.

Ending litigation abuse will create jobs (including union jobs), and prove to California’s skeptical taxpayers that public revenues can in fact be deployed timely to implement approved plans and projects instead of being bogged down in decade-long environmental studies and multi-stage lawsuits. For our famously frugal governor, ending CEQA litigation abuse has no economic cost, but will assure the timely completion of critical public and private-sector projects during his term.

We recommend legislative enactment of three moderate reforms to curtail CEQA litigation abuse:

1. Require those filing CEQA lawsuits to disclose their identity and environmental (or non-environmental) interests. It is an unwelcome surprise to many that an environmental law requiring public disclosure and transparency can be used as a litigation tool by anonymous entities for non-environmental purposes. Our study found repeated examples of intentional efforts to cloak the identity of CEQA litigants behind environmental-sounding names of fake and even unlawful “associations.” Federal courts have always required parties filing lawsuits under the National Environmental Quality Act of 1969 (which served as the model for CEQA, adopted in 1970). Even under California’s court rules, disclosure is already required later in the CEQA litigation process (e.g., for parties seeking to recover attorneys’ fees or file friend-of-court amicus briefs). The Judicial Council, which adopts rules of court for California, has decided that the decision to require disclosure of CEQA litigants should be made by the Legislature. The Legislature can and should promptly enact this long-overdue transparency requirement to end anonymous litigation abuse of this great environmental law.

2. Eliminate duplicative lawsuits aimed at derailing plans and projects that have already completed the CEQA process. For complex and multi-year plans and projects, scores of local and state agency approvals are required to complete plan implementation and project construction—and CEQA currently allows a new lawsuit to be filed against each new agency approval. Our study includes examples of projects (including infill projects) sued multiple times, with the most egregious examples including projects that have been sued more than 20 times (and resulted in delays that span decades). The study also includes examples of multi-decade sequential and sometimes overlapping EIRs to implement plans and projects, most notably including Herculean efforts by Los Angeles cities and transit agencies to complete transit systems and the higher density development patterns required for effective transit system utilization.

Once a plan or project has been approved, and has run the CEQA guantlet (including surviving a CEQA lawsuit), no new CEQA lawsuits should be allowed to challenge agency approvals that implement these approved plans and projects. As Seleta Reynolds, general manager of the City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation, patiently explained to a crowd of uncomfortable CEQA petitioner lawyers at the recent Yosemite Environmental Law Conference, CEQA reform is critical to the timely completion of transit systems. And both initial and operational funding for transit systems are dependent on actually achieving the higher density development patterns that create sustainable ridership levels, and are now enshrined in climate laws like SB 375.

3. Reform CEQA’s judicial remedies: preserve CEQA’s existing environmental review and public comment requirements, as well as access to litigation remedies for environmental purposes—but restrict judicial invalidation of project approvals to those projects that would harm public health, destroy irreplaceable tribal resources, or cause significant damage to the natural ecology. In our earlier study of 15 years of appellate court outcomes in CEQA lawsuits, we demonstrated that 43 percent of challenged EIRs failed to pass judicial muster, and an astonishing 60 percent of negative declarations (including mitigated negative declarations) also failed in court challenges. The most common judicial remedy, even for minor flaws in studies that can be readily fixed in a subsequent study, is to effectively rescind the agency’s project approval, and repeat the CEQA process and approval process. With these odds and this draconian remedy (and real-life examples such as the recent Hollywood apartment project in which tenants were evicted from a completed building based on a trial court’s CEQA decision about the level of CEQA process required for an already-demolished, non-historic structure), the mere fact of having a CEQA lawsuit on file can choke off access to the equity and debt dollars required to fund private sector projects.

Public sector projects are also at risk, since many grant and public funding programs require either “shovel-ready” projects with no outstanding litigation risks, or require utilization of funds by a deadline that falls well before the end of three-to-five years of CEQA litigation.

The practical reality is that the simple act of filing a CEQA lawsuit can choke off funding and effectively stop a project even if the lawsuit has no merit and is filed for non-environmental purposes.

In another shameful example of Sacramento’s insidious addiction to granting extraordinary dispensations to politically favored projects while leaving the rest of the state vulnerable to CEQA litigation abuse, former Senate Pro Tem Darrel Steinberg pushed through CEQA legislation that gave the hometown Kings basketball team the form of CEQA litigation reform we recommend, thereby assuring timely construction of this new basketball arena. The reaction was a chorus of criticism.

• The Sacramento Bee wrote: “No doubt, the proposed Sacramento arena could be a crucial catalyst for a more vibrant region and central city. But cities up and down California also have important developments on the drawing boards. Like the proposed arena, many are infill projects that create jobs, reduce sprawl and have few negative environmental impacts. Too often CEQA is exploited to stop good projects. Opponents who care nothing about the environment use the threat of CEQA lawsuits to leverage better labor deals or thwart a competitor.”

• The San Francisco Chronicle agreed, saying that Steinberg was “just plain wrong” and noting that “there are plenty of worthy projects around the state that are threatened by litigation under a law that is being exploited by individuals and special interests with motives that have nothing to do with the environment.”

As CEQA critic Governor Brown has explained, over the past four decades the courts have issued hundreds of judicial interpretations of CEQA that have morphed this great environmental law into a “blob” of contradictions and uncertainty—often misshapen, misused, mismanaged and, as shown by this study, used to thwart important environmental policies like climate change.

The Governor has his own challenges with CEQA: A high-speed rail lawsuit is currently pending in the California Supreme Court, and as Mayor of Oakland, he successfully lobbied for an uncodified, temporary CEQA dispensation to curtail CEQA litigation risks for downtown Oakland projects. His frustration with CEQA is perhaps best documented in an extraordinary brief filed with the California Supreme Court. He put it forward after an appellate court decided that building the townhome project included in an already-approved Specific Plan resulted in potentially adverse aesthetic impacts to the newly-built single family homes next door—and ordered construction of the townhomes halted at the framing stage, pending another year of CEQA study. Brown unsuccessfully urged the Supreme Court to overturn the appellate court decision:

• “Unless the [appellate court] decision is reversed, we are deeply concerned that our city’s elegant density policy of in-fill development will be undermined by long delays and expensive but useless analysis—analysis paralysis. …Since 2000, six separate EIR’s have been prepared for various of these [higher density, transit-oriented residential] projects at a cost of millions of dollars and unconscionable delay.” This “illustrates the profoundly negative impacts that the escalating misuse of CEQA is having on smart growth and infill housing” and “strikes at the heart of majoritarian democracy and long standing precedents requiring deference to city officials when they are interpreting their own land use rules.”

• “The [appellate court] found aesthetically degrading the “excessive massing of housing with insufficient front, rear and side yard setbacks [citation omitted]. Just as cogently, other people may well conclude that the close arrangement …fostered a cozy, neighborly intimacy. The fact that narrow streets are unfriendly to speeding cars and that neighbors are thrust into close contact may well be viewed as a superior quality of living rather than a negative impact.”

• “CEQA discourse has become increasingly abstract, almost medieval in its scholasticism. Nevertheless, if you apply common sense and the practical experience of processing land use applications, you will conclude that what is at stake in this case is not justiciable, environmental impacts but competing visions of how to shape urban living.”

The Governor has called CEQA reform the “Lord’s work,” but also recently observed that “Lord’s work” does not always get done. It is time to get this work done. As the editorial board of the San Francisco Chronicle recently succinctly summarized the challenge of CEQA reform:

• “The problem: The 40-year-old California Environmental Quality Act is vulnerable to exploitation from interests whose motivations have nothing to do with protecting resources. Lawsuits have been filed by labor unions as leverage for organizing and even by business competitors."

• "The solution: The law needs to be reformed to provide greater transparency on who is actually bringing a lawsuit, along with faster legal review and tighter guidelines on the basis for litigation.”

• “Who’s in the way: Environmental and labor groups are adamantly opposed to substantive reforms.”

Environmental groups want to advance California’s climate leadership efforts and should oppose CEQA litigation abuse against the transformative regulations, plans, and projects required by California’s ambitious climate agenda. As documented in our study, labor has lost countless jobs (and members) to CEQA lawsuits. California’s unions have suffered greater membership losses than the national average and other Democratic stronghold states. Union members (like other middle- and lower-wage workers) suffer from astronomical housing costs and transportation nightmares in the coastal counties where CEQA litigation abuse flourishes.

Ending CEQA litigation abuse will help California and the environment. Our leaders should lead us out of the morass created by this “blob” by adopting these three reforms.

- Log in to post comments