In advance of the November initiative Proposition 10, which seeks to repeal the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act and thus allow local governments to adopt rent control ordinances, the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy has examined the impact of rent control in the City of Los Angeles. The report, People Are Simply Unable to Pay the Rent: What History Tells Us About Rent Control in Los Angeles, surveys the history of the region and the “perfect storm” of affordable housing shortfall, rising rents, and declining incomes that have contributed to this ballot initiative. This report, authored by Alisa Belinkoff Katz, serves as a TPR follow-up to a previous interview with Related California’s Bill Witte affordable housing and rent control. Proposition 10 also states that a local government's rent control ordinance cannot abridge a fair rate of return for landlords.

"This crisis demands action. The time has come to reassess the City of Los Angeles’s Rent Stabilization and related tenant protection ordinances to address our most vulnerable, rent-burdened populations."

People Are Simply Unable to Pay the Rent: What History Tells Us About Rent Control in Los Angeles by Alisa Belinkoff Katz, introduction by Zev Yaroslavsky

Executive Summary

This working paper, the first of the newly created UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy, aims to realize the goal of adding historical perspective and depth to present-day problems. It rests on the premise that policy-making can benefit greatly from historical knowledge—and conversely, that we diminish our own capacity to solve present-day problems by ignoring history.

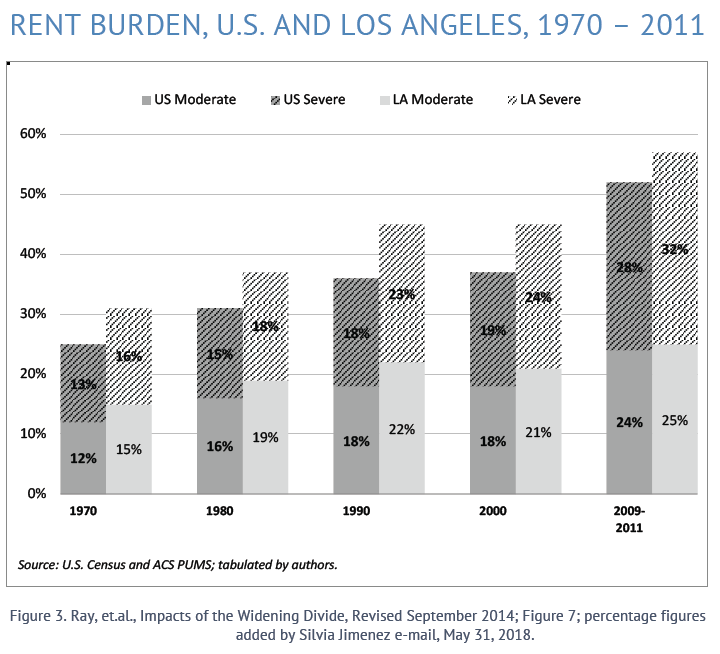

The case in point is the current affordable housing crisis in the City of Los Angeles, where rates of “rent burden” and, by extension, homelessness are reaching unprecedented levels. Of course, this is not the first such crisis that the city has faced. This paper examines two previous moments in which the city experienced a severe shortage of affordable housing stock. The first instance occurred in the early 1940s when hundreds of thousands of workers moved to the city to fill positions in the new war economy, overrunning the available housing inventory. Federal rent control in Los Angeles (1942-1950) successfully froze rents and narrowed the scope of evictions until housing construction expanded the city’s housing supply.

The second instance occurred in the late 1970s owing to a combination of high inflation and an interlocking rise in home values, property taxes, and rental rates. The Rent Stabilzation Ordiance (1979-present) ended dramatic rent increases for incumbent tenants by limiting the rate by which rents could be increased.

The current moment features a “perfect storm” of affordable housing shortfall, rising rents, and declining incomes that began in the early 1990s and has gained momentum to this day. These trends have made housing unaffordable for almost half of middle-income renters and nearly all those who are poor. This is turn has exacerbated the epidemic of homelessness on our streets.

Drawing on our history, this paper proposes a range of options to ameliorate the economic vulnerablility and anxiety of a growing number of our city’s rent-burdened residents. These options include extending the city’s rent stabilization law to certain units built after 1978 as well as to single-family homes; modifying the “vacancy decontrol” provisions of the city’s ordinance to better maintain what remains of its affordable housing stock; and extending just-cause eviction protections to all renters.

Many of these proposals require amending or repealing the state Costa-Hawkins law, a 1995 statute that largely pre-empts local government’s regulatory power in the rental housing space. Other options include more fully engaging the public in enforcement of the rent stabilization law.

The options offer tools to mitigate some of the negative effects of gentrification at a time of dynamic economic growth in Los Angeles. Finally and most urgently, the proposed options offer relief from the epidemic of homelessness that threatens the soul of our city.

Introduction by Zev Yaroslavsky

Los Angeles today faces a profound housing crisis that endangers the social fabric and public health of the city. And yet, this problem is not without a history. In the last eight decades, the City of LA has experience affordable housing crises caused by shortages and hyper-inflationary price increases.

These were periods in which city residents were forced to choose between staying in their homes or apartments at the expense of other vital needs or uprooting themselves from their communities in search of more affordable shelter.

Exploring the past allows us to better understand how we got to where we are today. Accordingly, this paper analyzes housing crises during three distinct moments in LA history: World War II, the 1970s, and the present moment. In each of these periods, housing prices reached crisis proportions.

Today’s housing affordability crisis is caused by changes in the Los Angeles economy that began in the late 1980s and early 1990s and led to affordable housing shortfalls, rising rents, and dwindling incomes. Though the causes and characteristics of the current crisis may differ somewhat from those of previous periods, the fundamental questions remain the same. Does government, particularly at the state and city level, have the tools at its disposal to aid LA rents in withstanding the economic pressures that they face? What lessons can be learned from our city’s history that may inform current policy? This analysis seeks to answer these and other questions at this critical juncture in our history.

Conclusion

Los Angeles’ history is marked by periods of severe housing affordability crises. Each of these periods was classified by unique social and economic circumstances. During World War II, rent control was part of a national effort to tamp down price gouging and support the war effort. The 1970s was characterized by hyper-inflation that drove up home prices and rents in predominantly White, middle-class communities.

Today’s crises is different. While seniors and other tenants in the 1970s were hard hit by rent increases, they were decidedly “middle class.” They had something to fall back on — job skills, small savings, or investments. When push came to shove, many could find ways to make do. The victims of today’s housing affordability crisis include the lowest-income renters who make up a much-higher percentage of the city’s population. They have little to fall back on – except the street.

What began as a problem for largely White, senior, middle-class tenants living in LA’s most desirable areas has turned into a problem for every segment of the rental population, from the very poor to the middle class to those who have been priced out of homeownership; from South LA to the Westside to the San Fernando Valley. What began as an effort to protect seniors living on fixed incomes is today not enough to keep renters of all ages in their homes and off the streets.

This problem extends beyond city boundaries as evidenced by rent control movements now active in Inglewood, Long Beach, Glendale, and Pasadena. There are also movements afoot to amend or repeal Costa-Hawkins and the Ellis Act. Indeed, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and the Los Angeles Times have endorsed the Costa-Hawkins repeal.

This crisis demands action. The time has come to reassess the City of Los Angeles’ Rent Stabilization and related tenant protection ordinances to address our most vulnerable, rent-burdened populations. The ability to effect change at the city level is limited by state law, but that does not preclude political leaders and concerned citizens from advocating for changes to that law and amending local law where possible.

- Log in to post comments