The Los Angeles City Controller’s office recently released an updated version of its online government asset mapping tool, Property Panel, which identifies all publicly-owned properties in the City of LA. With Step 1 complete, TPR Spoke with Controller Ron Galperin on his latest announcement proposing the creation of the Los Angeles Municipal Development Corporation, a nonprofit entity that would be tasked with managing identified assets in a more strategic way. Galperin highlights opportunities for the city to put underutilized assets to work while meeting the service needs of communities across LA.

"It has been my interest to see how we can best leverage and manage these city assets, and how we take a necessary and holistic look to accomplish important city goals.” —LA City Controller Ron Galperin

You recently announced a plan to establish a LA Municipal Development Corporation that would enable the city to manage the property it owns more strategically. Describe how the city currently manages its real estate, and then what your proposal does to reform that process?

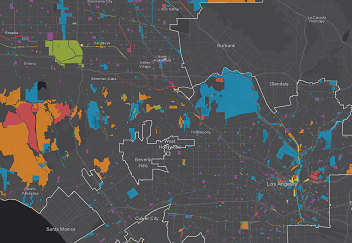

Ron Galperin: Currently, the management of the city’s real estate is very fragmented. When I first came into office, I was dismayed by the fact that the city didn’t even have a list of every property that it owned, much less have it mapped. That was one of the first tasks that I set about. We came out with our Property Panel, which mapped all the properties that were owned by the city. As you may know, there is a 2.0 version of that that we launched just two months ago with a new, easier-to-use platform. It also includes all properties within the City of LA that are owned by LAUSD, Metro, the county, the state, and the federal government.

I wanted to provide a real picture of all the properties in LA that are owned by a government entity. The City of LA is arguably the largest owner of real estate in Los Angeles, with 7,500 distinct parcels within the city. Some of them are slivers and some are wonderful parks or municipal buildings, but we also have a vast portfolio of underutilized commercial, industrial, residential, retail, and parking properties. It has been my interest to see how we can best leverage and manage these city assets, and how we take a necessary and holistic look to accomplish important city goals whether it’s about low-income, senior, and homeless housing, open space, or projects that can generate a revenue source that can help fund the many things that we want to get done in the city of LA.

How difficult was it to amass and intelligently process all the data collected?

When we first went about it, we looked at a whole variety of different sources. For example, we went to departments and asked for whatever lists they had. Though, I have to say one of the most important sources of information that we had was the LA County Assessor where we got a lot of help and collaboration.

It ended up taking over a year to actually put it together, because we really wanted to make sure that we properly vetted what we were putting down, and that our list was comprehensive. We’ve been working on this newest version for probably six months in order to get the databases, and make sure that we got clean data on the property that is owned by other government entities as well.

When TPR interviewed you in 2016, you spoke of the city’s need for a chief asset manager. Is such a manager still needed?

Is it still true, although what I have done in this round is put forward what might be considered a more modest and, hopefully, achievable proposal. There have been many attempts to create something akin to a chief asset manager over quite a number of years, and it didn’t happen. What I set out to do was study the other proposals, why they didn’t come to pass, and what we could do to address some of the concerns. One of the primary concerns—either stated or unstated in the past—was that there are always existing departments, interests, or people that are vested in the status quo.

Our new proposal creates the entity or the framework, but it’s not going to manage every city property. Properties are going to continue to be managed the way they are on a day-to-day basis by the departments that already manage them. What this would do is provide an opportunity—for the entity itself, board members, councilmembers, and the mayor—to come up with an initial list of some properties that are worth exploring. And, to be able to evaluate properties that may have some potential, negotiate, and move proposals forward. If a councilmember has a project they’d like to see happen, this entity would help them to effectuate that and bring the necessary expertise to identify, negotiate, and manage the project.

Elaborate on the leverage opportunities of the city having this property ownership data – data long wanted by the council, the city, the supervisors, and even the state.

There are leverage examples that exist right now in Los Angeles; and one that’s currently under construction: a former LA city parking lot on Pico near Robertson. It’s now going to have affordable housing, but still provide parking for the businesses that are there. It’s an area that has a vibrant business community, but also a desperate need for more housing. This gives us an opportunity to maintain the parking, but also to create housing above it.

Those who are in the real estate business are in the business of thinking creatively and entrepreneurially to create something that never existed before. Government, by its nature, does not necessarily think entrepreneurially. It thinks more in terms of RFPs and RFQs than in terms of putting a deal together. The idea is that this entity would help to bring some of that expertise and entrepreneurship to the city.

Let me also add that this idea—a LA Municipal Development Corporation—is based on models that have been successful in other cities; we don’t have to reinvent the wheel here. We have studied New York’s Economic Development Corporation, Philadelphia’s Industrial Development Corporation, and Copenhagen’s Port Development Corporation.

Another example—although it’s a different kind of entity—is the Port Authority in New York. The Port Authority is largely a kind of state entity, but the island of Manhattan is significantly larger and has more acreage than it did 100 years ago. That happened because the Port Authority essentially added land and created places like the World Trade Center and Battery Park City; they created something out of nothing. We would be a very different kind of entity, but you can see models throughout the world of how a pseudo-government entity can be a partner in creating tremendous value for a city.

Some in the state legislature wish to wrest control over local zoning and planning to incent great housing production in coastal California. To defend their taking of local authority, they argue localities have resisted efforts, negligent even, by developers to produce more housing. Is your new proposal of a Municipal Development Corporation a sign that the city of Los Angeles has its hands around this problem?

I don’t know yet if the city has its hands around the problem, but I do sense a greater willingness and urgency than before. The situation that we have with the lack of affordable housing is a crisis that has been in the making for decades; nobody should be surprised that we are where we are now. If you make it incredibly difficult and time consuming to build, you’re going to end up with less housing than you need. If you have a real imbalance between supply and demand, it’s going to be really expensive. There are people that are going to be left out, and in this case literally left out on the street. We need a different approach to how we can encourage the kind of development that is going to be a benefit to everybody.

We want to see projects that meet a whole long list of requirements that may in fact be very important, but the more requirements that you have in place, the more expensive and the less of those developments that you’re going to see. We have environmental laws—which are often for good reason and with good intention—that can be taken to an extent that hampers much needed development and housing. It’s no surprise that we are where we are now, the question is whether there is the political will to break through the bureaucracies that exist and deliver.

Are you suggesting that perhaps the city’s control over zoning and planning ought to be given up to the state?

No, I’m not a fan of that. I think different cities throughout California and the nation have different needs. I do think it’s healthy that you have coordination between various levels of government, but local land use has long been the purview of local government. It is vital, however, that the city of Los Angeles and other cities really take a look at how they can create more housing.

By the way, there are other cities that have really blocked the creation of both market-rate and affordable housing. LA—while we have a very long, complicated bureaucratic process sometimes—has welcomed a lot of that and has created a lot more housing than anywhere else in the state, but just not enough to keep up.

Can you give our readers a deeper insight into the possible opportunities that can be leveraged with this data the Controller’s Office has assembled?

First and foremost, before you can even talk about managing or leveraging anything, you got to know what you own. It was vital to me to finally have one place where not only those within the city, but anybody could go online anytime, and see what it is that we own. That was only a first step for me, but let’s say a developer has a great idea for something that can create housing or value and utilize an underutilized property. Right now, there’s really no good methodology for what happens if they’ve got a great idea. They would probably go to the council office, they might go to one of the various departments, and they’re likely to be referred and ping-ponged back and forth from one place to another. Having an entity such as the Los Angeles Municipal Development Corporation would be a one-stop shop for those that have a good idea, and a place where the councilmembers themselves can turn to for help and expertise.

We have a whole variety of different kinds of properties that are underutilized. Take a look at the Los Angeles Mall, right next to City Hall East. You’ve been there many times, is there a more pathetic mall in all of America? I think not. Imagine the possibilities. Look at what Long Beach is doing with its civic center. We have the West Los Angeles civic center as well, that could be a crown jewel in so many ways, and yet it has been floundering for years. Another example, on a smaller scale, that continues to be one of my pet peeves is on Arlington just north of the I-10 freeway in Mid City. There is what used to be an old Los Angeles City library that was replaced quite a while ago with a brand new one. That building, which is a corner building, is a beautiful piece of architecture that can be used for so many different things and yet—after at least a decade or more—it’s fenced, often overgrown with weeds, and an eye sore when it could be an amazing benefit to the community in so many different ways.

Coming soon are rules and regulations for private investment in Opportunity Zones—nearly 900 of which have been identified in California. Do you see a nexus between the private investment of that capital and the property assets that you’ve identified in the City of LA?

Absolutely. I think opportunity zones are really going to be an important and valuable tool to help realize improvements and community development in parts of Los Angeles that could really use it. If you take that and look at all the properties that are publicly owned by government entities, you can take some of the benefits that we hope will happen with opportunity zones, and further leverage and multiply it.

This proposal is not about how you take every property and maximize it. This is not about how you manage every property, or have all of it under one umbrella. This is about how you can leverage some of the most valuable and underutilized properties that we have, and how you identify needs in communities across LA to help meet those needs.

A recent report from the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project finds that investment firms like Blackstone are the largest owners of residential real estate in Sacramento, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Might their findings suggest how the city and state legislature should approach formulating housing policy – going forward?

A lot of these firms have acquired real estate in different ways. Some of it has been through acquiring existing multi-family projects, and some of it was a result of the foreclosure crisis that we had during the 2008 recession when a lot of people lost their homes, which ended up being bought by investors.

What you are putting your finger on is another issue that is of great interest to me. We do a lot of talking about creating affordable housing in LA, although we don’t do enough of it. We also do a lot of talking about the importance of having workforce housing, and do even less about that. The numbers show that the percentage of people in LA who are actually owners has been declining. Almost all of what is being built right now is rental, and not ownership. I think over the long term, that can have a really negative and even corrosive effect on a society. When you have a smaller and smaller percentage of those who can actually buy into the American Dream, build wealth, and equity, you have a growing number who are locked out from ever owning anything.

We need to have a real conversation not only about creating affordable housing, but about creating more opportunities to own. I have a lot of ideas and thoughts on that, and I eventually want to do a report on that. It’s a very interesting subject for us to explore. That is crucial, it’s not just about more apartments, it’s about more opportunity for people to actually own something.

Pivoting to another subject: A local measure that was introduced on the 2018 ballot to create a platform for establishing a city-owned bank failed, but the issues that drove it—the current inability to bank cannabis transactions—has kept alive the quest for a public bank. As someone knowledgeable about finances and the city, what are your thoughts on a local-level solution for legally banking cannabis revenue?

Ultimately, on the subject of cannabis, there will need to be a more federal solution. The state of California is one of many states that has now legalized cannabis. I don’t think that keeping those businesses unbanked and the federal regulations that are in place right now have done a service to anybody. I am hoping that there is a growing recognition on the federal level that this needs to be resolved.

Even if an institution was created locally in Los Angeles, the lead time to do that is very lengthy, the capitalization requirements for creating a bank are substantial, and the expertise that you need to run a bank is significant. If cannabis transactions are the only reason to create a public bank, that reason will evaporate at some point.

It’s valuable to have a conversation about whether the city might have some kind of a banking entity, but it’s not a simple matter to create one. If you’re looking for just the city’s treasury to be the capitalization, that’s not enough. Moreover, the city’s treasury has to be well diversified. With that said, I think there are some elements there that are worth considering, but they’re not going to be the long-term solution to banking cannabis.

In closing, have the city and state been engaged in crafting an interim solution to legally banking cannabis revenues?

There have been conversations, and there are a variety of different kinds of temporary solutions that have been proposed. I had issued a report about two years ago looking at cannabis collections and a whole variety of different recommendations that we made—how to handle cash and what some alternatives could be. In terms of banking, not enough progress has been made on this issue. But again, this is not a unique problem to LA or to California. You’re really going to need to see a change in regulations. That was really on the cusp of happening before the end of the Obama presidency and even under the Trump administration. At first they were sending signals that they were open to exploring the idea, but it seems to have gone nowhere since then.

- Log in to post comments