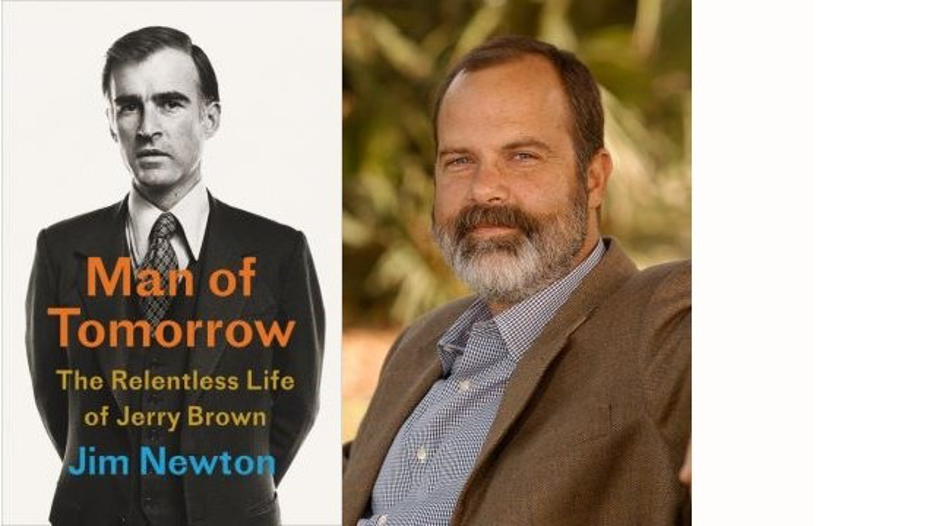

With the exclusive cooperation of Governor Brown himself, Jim Newton, former Editor of the LA Times, has written a definitive account of Jerry Brown's life, “Man of Tomorrow”. As Senator Diane Feinstein notes: “His book captures the complexities of a man who is both a bold visionary and a practical leader, someone who transformed California into the model for fighting climate change while building the fifth-largest economy in the world.” TPR excerpts here, a May 12th Los Angeles World Affairs Council & Town Hall featuring Newton’s interview of former Governor Jerry Brown on, among other issues, the current status of COVID-19 in the US context and its impact on national politics. Watch the full conversation here.

Jerry Brown

“We've got to find a way of containing the worst of our nationalistic senses, feelings, and fears. If we don't, the world is small enough and dangerous enough that I would see a very dark future if we can’t wake up and take this broader, what I call, planetary realism.” —Fmr. Gov. Jerry Brown

Jim Newton: Governor, I don't want to monopolize you this morning but I did want to ask you a couple of things to get the ball rolling, and also give you a chance to address some of what's going on in the world at the moment.

We're in this period of international crisis and particularly at this inflection point where there's an ongoing and accelerated debate about how to balance the health imperatives of this crisis with the economic desire to see things return to some kind of normal. Dr. Fauci was testifying this morning in Washington and said that he fears that some states may move too quickly in defiance of the guidelines and risk a spike in the virus.

You've obviously weathered your share of crises; how do you balance the imperatives here in particular the desire to see the economy move again and the need to be to take care of the health imperatives?

Jim Newton: You've obviously weathered your share of crises; how do you balance the imperatives here, in particular the desire to see the economy move again and the need to take care of the public health imperatives?

Jerry Brown: You do it in the same way that the successful countries have—looking at perhaps the most successful country, Taiwan. They've had very few cases and very few deaths. They took action as soon as China sent out a message, right around the beginning of this year. Taiwan heard it; Mr. Trump and the people in Washington didn't. Taiwan jumped on it; they started testing, tracing the people who tested positive, and quarantining them, which really dampened the spread in a very dramatic way.

We didn't do this; we had denial, delay, and obfuscation. The big hurdle here, which is being overcome, is the inability of testing, and to me that goes right back to the President and in some ways his enablers, starting with Mitch McConnell. We can’t test because the federal government has not used the powers that it has to mobilize the industry to make tests. Nobody can tell me that South Korea or China can make tests better than America, this is a great manufacturing powerhouse, and an innovative biotech powerhouse as well.

The fact that we don't have the tests we need—not by the hundreds of thousands, but by the tens of millions every day—is leading to the problem we’re at now. It's getting better slowly, and over the next couple of months, we'll have enough tests.

One of the biggest causes of spreading in Wuhan was isolation at home and the spread in families, so it's pretty simple: you test in massive numbers. California is doing maybe 30,000 and now it's got a ramp up to a several hundred thousand if you really want to be careful. You want to open up the schools? You better test a lot of these kids, otherwise you're not going to know. There's no conflict between an energetic creative testing program—with tracing and quarantining—and opening up the economy. The longer you wait, the harder it is and the more people get sick, suffer, and die.

That's where we are and we can't just look backwards, we’ve got to look forward. First of all, Congress should be demanding—because Trump's not doing it himself—that they mobilize the industry. Now, the industry is doing something but you can't leave it to the fragmented decision-making of all these different people. I think back to Roosevelt on some day in 1941, he said no more private cars; Americans are making tanks, planes, and liberty ships and that's exactly what happened. They could put out planes and ships in a matter of days, so why can't we put out tests. We're going to get there, but we're going to get there over a lot of totally needless suffering and death, and it all goes back to Washington in my opinion.

Jim Newton: One of the things Donald Trump has said is that he would like to condition federal aid on certain policies in states. For instance, the federal government might withhold aid from states that have sanctuary policies for illegal immigrants. What do you think about linking aid to other policies, and what's the role of the federal government in aiding states in this crisis?

Jerry Brown: The first Justice White, in the 19th century said, “to state the proposition is to refute it,” and I say that because if you want to return the country to vigorous activity, you don't go around and saying, ‘California, I don't like what you're doing’ or ‘New York, I don't like your politics’.

To get the whole country back, you need us unified, and you need to follow the spirit of Roosevelt: try something, and if it doesn't work, try something else.” We need bold, persistent experimentation, not partisan rancor, petty politics, or halfway measures. To get this economy going with so many people sequestered at home requires massive federal spending and investment, for two clear objectives.

One, income maintenance: to supply the purchasing power that millions of Americans no longer have. They need that for their families, themselves, their food, and for their basic sustenance.

Two, investment in infrastructure: whether it's roads, high-speed rail, highways, or extending the internet to rural areas, schools, or community hospitals that are closing. There are trillions of dollars of good spendable projects.

It’s very simple. The economy is the function of supply and demand, and demand has collapsed because of the virus. That demand is the basis of an economy; you need supply, but you also need to have somebody seeking the supply and paying for it. percent of American demand is from consumers, and many of those consumers are not exercising their capacity. Therefore, the federal government must come in and supply that. So, I would call this a Rooseveltian moment, and it ought to take into account all the problems we have, whether it's the maldistribution of income and opportunity or the impending challenge of climate disruption. All these things are on the table, and unfortunately if we can't do them right in calmer days it's going to be very difficult.

The country has to step up—starting with the president and going down—and there’s been some cooperation. We're getting more testing in California—and President Trump is cooperating in some ways—but we need something much bigger. Roosevelt did not rise to the occasion at the level that the economy required. In the late thirties, a second way of unemployment came back, the recession intensified, and it wasn't until World War II—with mass mobilization of the entire economy for war material and soldiers—that we really got the economy going.

What Roosevelt did in the ‘30s and early ‘40s is what is required—certainly not a war—but hopefully a domestic campaign, intervention, and mobilization of the very best that America stands for. Anything less than that is muddled, isn't entirely predictable, and the odds will not be pretty.

Jim Newton: You talk about this as a Rooseveltian moment, do you have any reason to believe that Trump is capable of a Rooseveltian moment?

Jerry Brown: Well, I don't put anything passed him, but it doesn't look that likely. Not only he but his so-called base has a quasi-theological belief in this thing they call ‘the market’. The market, as its most beloved acolytes say, does not function well if there is interference or more than a minimal role for the state.

What I'm calling for—what Roosevelt did—was a great intervention, and he was looking to Keynes as opposed to Hayek. Right now, we're more in the Hayek realm than we are on the Keynesian, and I think that will cause us great heartache in the months and years ahead.

Jim Newton: Let me ask you about one aspect of this crisis and climate change that seems to run in common: denialism. There's at least some segment of this country that really doesn't accept that this is a serious health crisis; what do you make of that and what's responsible for that? In terms of climate change, there's also a streak at denialism. Where does this come from and how do we deal with it as a policy?

Jerry Brown: We’re in an increasingly polarized country—not that we haven’t been there before; we had a Civil War. We had a lot of people that hated Roosevelt—and Roosevelt had his own antagonisms—but it has gotten far worse.

First of all, what are the characteristics? If you're a Republican in California, you’re only 23 percent of the voting population, and 80 to 90 percent inclined to believe in President Trump. If you're a Democrat, that’s probably under 10 percent.

According to a poll that I heard from Republican writer, John Fund, only 37 percent of Republicans are worried about the health aspects. Whereas, if you ask Democrats, 97 percent are worried about the virus and the health aspects; There, we have a fundamental difference.

What caused it? Well, I'd say it’s a function of the income maldistribution, the propaganda that we see coming out of the spending in climate denial and the views promoted by Fox News and the right. But also, I'd say that the emergence of people of color and the assertion by women for a greater and equal role in the different countries of the world, taking on a greater role in every way, is causing angst and identity anxiety, particularly on the part of people who are in my bracket: people who are male and white.

You saw it with the antagonism to Obamacare by the Republicans. It became an article of faith that indicated not so much medical spending by the state, but more something new and different. the Republicans were able to characterize it as something un-American; a threat to the well-being of people, even those who were getting the benefits of the Affordable Care Act. There are a lot of factors that historians and analysts can come up with, but suffice it to say the changes in America are being felt disproportionately by different groups—whether people are Latino, African American, European Caucasian, male, female, rich, poor, rural, urban. We're seeing through different lenses and that is causing tremendous polarization. The election—it's very close, the betting odds are on Trump, and the polls are showing Biden by three to six points.

This is a divided and overextended society that is borrowing in a very exuberant way. I'd say we have a lot of challenges and probably the biggest is building trust by our leadership, which is now being done better by the governor than by those who are occupying the power pole position there in Washington.

Jim Newton: There's polarization, but what strikes me as different about this moment is that it seems that belief in science itself has become a matter of partisan difference rather than a common base upon which to disagree in terms of policy solutions. How does this polarization contribute to our different understandings of what science itself would say.

Jerry Brown: I don't know that people are thinking about science. Let's just take climate change, for example. There is a lot of denial, and it's more found among business Republicans and more conservative-type people, that's just a fact. I don’t know if it's the science or if it's the belief and trust in this magic of ‘the market.’ The market faces a totally new world when climate change requires a government-induced price on carbon or certain zero-pollution standards to eliminate carbon emissions for cars so that we can avoid the worst of the climate changes.

Is it a scientific matter or is it this belief in wealth and the economy? Why is tax the central pillar of the Republicans? Now, there are some religious ideas and other moral issues, but there's nothing so unifying as tax: less tax good, more tax bad. It’s money going from a private pocket to the public wealth. Democrats don’t want to pay more taxes than are needed, but I would say that there is a magical belief that you can reduce taxes and therefore gain government support, far more among most Republicans than among independents and Democrats.

Whatever it is, you’ve got this belief that’s different for Democrats and extremely different from Republicans, with independents shuttling in between in some fashion.

The issue for politicians is working through this divide in order to find common themes that can bring people together, because the world is certainly getting more dangerous for natural reasons—like pandemics and climate change—the interdependent financial system, all the new technologies that have so much power, and the weapons business that is accelerating. Even in the midst of the COVID crisis, Congress is considering tens of billions of more dollars to confront China, Iran, Russia, and all the other adversaries that are certainly different, but are being magnified in order to boost the defense industry and fan the flames of widespread fear and anxiety. I think we're in a very difficult political environment that will take great skill and a fair degree of luck to get through, without even greater disasters than we've seen more recently.

Jim Newton: Look ahead—beyond this virus or to a point where things seem to have settled down—how does life seem different to you? What are some of the ways in life will be different? Does life go back to normal as it was six months ago, or does life look different two or three years from now?

Jerry Brown: That's a difficult question. It's not clear we’re getting a vaccine anytime soon in the next year or two, and even when we get it, it's going to be hard to distribute it. If we don't get a vaccine, the airlines aren't going to come back to normal. Restaurants are going to come back, but there's going to be a change.

Behind your question is a larger point: are we going to learn something from this pandemic about how we want to live or how we must live? This is not a one-off story for a week or two; this is the persistent new reality that is going to induce more reflection. People will probably spend more time at home cooking and sharing meals with their family and friends than they have years before.

It wasn’t that long ago, when I grew up in a middle-class family—you might say it was a little better than that as my father was a lawyer and then the elected District Attorney of San Francisco—we might have gone out once or twice a year, maybe a few more times, but nothing like what is standard practice todat. I didn’t go to Europe until I was in law school, yet today many families, middle-class and above, are flying all over the world.

Things have not been the same as they have been the last decade or two, so they will change. I think there could be some good out of that, but mostly I think what I'd like to see society learn is that when you see a threat, you’ve got to take it seriously. Taiwan responded because they acted on a small amount of information, but they inferred that this pandemic would spread if they didn't take very drastic action. On the part of Italy, many European countries, and the United States, we didn't want to act; we wanted more certitude. Well, they're going to be more pandemics.

We have things like the danger of war. Can the United States make China a more hostile and more hated enemy month after month without having a war? Can we do that? I have my doubts. I think we're going to have to learn from the pandemic that you must take danger seriously and you have to listen to science. This world is not me versus you—it’s not a linear, zero-sum give and take—it's mutual, and it's interdependent.

The virus did not come from nationalism. It didn’t come from the way all politics is oriented with winners and losers. We are on a planet, and we share among 7.7 billion people this atmosphere, the soil, and all the human systems we created. We have to find mutuality and commonality, and that doesn’t mean we have to mean agree all the time, but—just as in a war—in a crisis, people unify.

This is a crisis not of China versus America, but it is human beings who live in China, America, Russia, and India all facing some very common threats—including climate change. We've got to merge out of ‘We win, you lose,’ to a world that is more collaborative. That might sound like pie in the sky, but we can adopt some form of a more shared world, or more of a win-win situation, or we really do face a high prospect of extinction or at least many horrors beyond those which were encountering today.

Jim Newton: It sounds a little like Schumacher, Small is Beautiful.

Jerry Brown: Well, I’m not saying small is beautiful; we have Google, high-speed rail, airplanes and vaccines, and that's not a ‘small is beautiful’—there’s a hundred vaccine companies out there. I think it is a recognition that we are not isolated, but that the air, the carbon emissions, financial system, the germs, and viruses spread around the world; we have to find the common way forward that would link Russia, China, the US, India, and Iran.

They're going to be big differences, but doesn't mean we can't coexist. In some ways, we coexisted with Russia, and we were in absolute antipathetic positions. World communism or the freedom of the West was going to dominate, and somehow, we invited a nuclear war and a lot of conflict and skirmishes on the periphery.

We've got to find a way of containing the worst of our nationalistic senses, feelings, and fears. If we don't, the world is small enough and dangerous enough that I would see a very dark future if we can’t wake up and take this broader, what I call, planetary realism. Look at the world from the totality, the interdependency, and the interacting, not from it’s either us or them. In truth, if China's economy declines, it affects us the same way our economy or the European economy declining hurts China. We've got a lot in common even though we have profound differences, and it's the wisdom to negotiate those differences in the context of embracing the commonalities that the future lies.

- Log in to post comments