After six months, the TFAR proposal is still being considered by the City Council for review. Larry J Kosmont and Charles E. Loveman, president and vice president of Kosmont & Associates, respectively, return with this article further detailing the importance of the resource allocation tool that is TFAR. Loveman and Kosmont accomplish this by providing a hypothetical example and a graph depecting the inverse relationsihp between required subsidy amount and th number of FAR's eligibile to be transferred.

When last we visited the TFAR issue in The Planning Report (see here), a density pricing proposal had just been approved by the CRA Board of Commissioners and sent to the City Council for the Council’s review and adoption. Today, six months later, the issue is still being considered at the City Council committee level.

Judging from the lack of Council action on this item, we can suppose that the Council offices and City staff are uncomfortable with some aspect of the TFAR policy sent to them by the CRA. Therefore, it seems appropriate to revisit the issue, with the intent of focusing this important planning and financial tool on the critical problem of producing Downtown housing.

TFAR in Perspective

To begin, let’s put in perspective how important and economically productive a tool the transfer of floor area ratios can be. In any given year, an average of approximately one million sq. ft of new office space is constructed in Downtown Los Angeles. Of that total, about 400,000-500,000 sq. ft consists of floor area transferred from some other location. The current price paid by recipients of this extra floor area is $40 per sq. ft, including both the cost of the unused density plus the so-called Public Benefit Payment.

Thus, with office developers paying $40 for about a half a million sq. ft of transferred density in a typical year, some $20 million annually is generated by this mechanism, on average.

In terms of housing, what will $20 million buy? Again, using historically typical numbers, on average the CRA has subsidized rental housing in South Park at a rate of approximately $50,000 per unit. The $50,000 figure is a typical per-unit subsidy on a “generic” project basis, which, for purposes of this comparison, is a 200-unit project with about 25% of the units classified as affordable housing (both low and moderate income) and 75% “market-rate” housing; the “prototype” project also includes some ground floor retail use.

If the entire $20 million generated annually by TFAR were directed to housing production, some 400 units per year of market-rate and affordable housing could be produced from this mechanism alone. As a comparison, this is $5 million more than will be produced by the controversial $5 per sq. ft. linkage fee (which, assuming that about 3 million sq. ft of new office construction occurs in the City of Los Angeles in an average year, will produce about $15 million annually).

Downtown Housing as a Highly-Advantaged Donor Use

By any measure, TFAR revenues represent a potentially significant source of money. Recall that the fundamental purpose of TFAR programs, as used in other cities throughout the country, is to enable below-market land uses, such as housing, hotels, and historic buildings which otherwise can’t afford high Downtown land prices, to compete on a level playing field with highest and best market uses.

So how can we make housing a highly-advantaged density donor use? The biggest obstacle is that most housing developments will typically use nearly all of their allowable “as of right” density envelope. Thus, our prototype housing project has little if any extra density to sell. However, if the floor area for a South Park housing project is, defined as zero for purposes of a density transfer transaction, then housing uses would have substantial unused floor area to sell.

This “Zero FAR for Housing” proposal would need to be supported by a pricing policy which clarified at the outset that the sale of unused development rights from certain, eligible housing sites would automatically qualify for a direct pass-through of the Public Benefit Payment, rather than that payment being collected by the CRA.

This policy would establish a new density “asset” which, depending upon prevailing market conditions, could be converted into a substantial amount of cash to help subsidize housing in Downtown.

Zero FAR for Housing: A Hypothetical Example

To examine this concept more closely, first let’s define our generic South Park rental housing project in more detail. Assume the project is to be developed on a 40,000 sq. ft. site with a 6:1 “as of right” FAR. Within the 6:1 FAR envelope, we will develop 1 FAR of ground floor retail, 3 FAR’s of market-rate housing, and 1 FAR of “affordable” housing. Our project thus uses 5/6 of its allowable density envelope, and so has 1 FAR (i.e., 40,000 sq. ft.) to sell to a density recipient.

Total development costs for our project (not including land) are about $27 million, and the capitalized value of the income stream is about $26million. Thus, we have a $1 million gap, and we haven’t yet addressed how to purchase the land, which has a market value of about $180 per sq. ft ($30 per FAR sq. ft.).

To close the gap between our project’s cost and its value and to pay for the land, our project needs a public subsidy of about $33 per FAR sq. ft of land. In other words, not only must the land be contributed to the venture for free by the public sector, but our project will also need another $3 per FAR sq. ft of subsidy in addition to the free land in order to “pencil out.”

However, if we are able to sell the unused 1 FAR of our 6:1 zoning envelope, and have all the proceeds from that sale (including both the Public Benefit Payment plus the purchase price for the transferred floor area) directed entirely to our housing site, then some $1.6 million of cash can be contributed to our project (40,000 sq. ft at a $40 per sq, ft).

With this additional cash, we can reduce our subsidy requirement to about $25 per FAR sq. ft. In other words, we can afford to pay only $5 for land which is worth $30 per FAR sq. ft.

The numbers improve somewhat if we can sell the 1 FAR of “affordable” housing in addition to the 1 FAR of unused density. In this case, we need a subsidy equal to about $18 per FAR sq. ft. of land, after accounting for the density proceeds. In this case, the most we can afford to pay for our site is $12 per FAR sq. ft., as compared to its true market value of $30 per FAR sq. ft.

But what happens when we sell all of the floor area occupied by the housing use, including both the market-rate and affordable units? In that case, we have 4 FAR’s of housing to sell in addition to the 1 FAR of unused density. By the simple act of changing the Zoning Code to define Downtown housing as having zero FAR for purposes of transfer, we’ve added some $8 million to our project (4 FAR's of housing plus 1 FAR of unused density at $40 per FAR sq. ft. for a 40,000 sq. ft. site). Or, in the words of the song, “Money for Nothing.”

With the additional $8 million, our generic project can now afford to pay about $35 per FAR sq. ft. for the site. The cash generated by being permitted to sell all our housing floor area more than equals our land cost (" ... and the Land is Free")

Economic Interrelationships

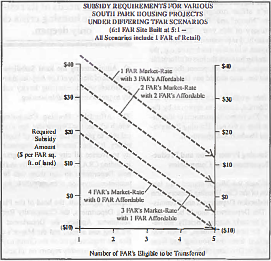

To show these economic interrelationships pictorially, the accompanying graph illustrates how a project’s use mix and the amount of FAR it has to sell affect its subsidy requirement. Each line within the graph describes a different project mix, i.e., a project of 1 FAR of affordable housing and 3 FAR’s of market-rate housing, another project of 2 FAR’s of affordable housing and 2 FAR’s of market-rate units, and so on.

The graph demonstrates a couple of obvious facts, namely: (1) that as the amount of FAR’s available to transfer increases, the subsidy requirement decreases; and (2) that as the ratio of affordable units to market units increases, so does the subsidy requirement.

But the graph also shows that selling only the unused and affordable housing floor area isn’t sufficient to eliminate the subsidy requirement. The floor area occupied by the market-rate units must also be transferred in order to make the project work. And that conclusion needs to be emphasized. If there is a policy direction to build housing for a broad spectrum of income types in Downtown, then so-called “market-rate” units will need some form of subsidy, in addition to the subsidy for affordable units.

Implications

What are the implications of applying the 1FAR tool toward housing in the manner suggested? There are several. On the plus side, a source of funds for housing can be created, by a simple change of definition in the Zoning Code, which has the ability to make Downtown housing self-subsidizing, and doesn’t cost the public sector any cash out-of-pocket. On the negative side, particularly from the CRA’s perspective, the public benefit monies would flow directly to qualified housing sires, rather than being collected and distributed by the Redevelopment Agency.

Also, for the CRA and the City, there is an opportunity cost to this mechanism, inasmuch as South Park density proceeds were otherwise intended to reimburse Convention Center cost overruns.

Another result of making housing the most advantaged 1FAR donor is that office developers will presumably be highly incentivized to team with housing developers (whether they be for-profit or non-profit) to build units in South Park.

On the positive side, that arrangement will probably produce housing more efficiently than if the majority of TFAR proceeds (the Public Benefit Payment) is given directly to the CRA. On the negative side, the value of unused housing density, and hence the amount of self-subsidy which a South Park project can generate, depends on the continued strength or weakness of the Downtown office market.

The potential for this application of the 1FAR process is not limited only to Downtown housing. This “Zero FAR” approach can be utilized elsewhere in the City, as well as for other Downtown uses.

For example, the Ventura Corridor Specific Plan can productively use floor area transfers to create more neighborhood compatible “pockets” of development which would include mixed-use retail and housing projects. Elsewhere in Downtown, we could subsidize convention-oriented hotels, ground floor retail spaces, and any other uses which otherwise would require a public subsidy.

And as a strategy for creating Downtown housing, few public policies seem more efficient.

- Log in to post comments