In a “Which Way, L.A.?” episode that aired on March 10 titled “Who Is Leaving Los Angeles Because of Housing Prices?” host Warren Olney considered the affordability crisis facing Southern California and the re-definition of the Los Angeles dream. TPR presents edited excerpts from the program featuring Jordan Levine, Director of Economic Research at Beacon Economics; Joel Kotkin, Urban Studies Fellow at Chapman University and a member of the Orange County Register editorial board; and Christopher Hawthorne, architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times.

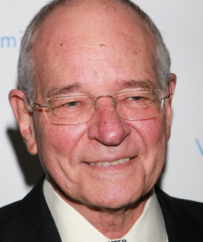

Warren Olney

"In Southern California, we just don’t have enough supply of housing—be it affordable housing, but more importantly, just housing full-stop." -Jordan Levine

"The promise of Los Angeles always was, in the postwar decades, that you could afford to move here and get a slice of that LA dream even as a middle-class family. That meant a single-family house and a garden... Now that the city is built out and housing costs have gone up so quickly, that dream is disappearing for a lot of people." -Christopher Hawthorne

Warren Olney: The median price of a home in the LA metropolitan area is around a half-million dollars. What’s the breaking point? What do you have to make to be able to afford to stay here?

Jordan Levine: When you look at who’s migrating out, the vast majority tend to be folks with an income below $50,000. Folks in the middle are finding it the most difficult to grapple with the ownership cost and the cost of rent in LA.

Warren Olney: Elaborate a bit more on who these people are that are moving out and have lower than $50,000 incomes.

Jordan Levine: Actually, if you look at out-of-state migration, the vast majority are making below $50,000 a year.

But looking at within-state migration, folks moving from coastal areas like LA and Orange County into more inland economies like the Inland Empire would otherwise have been in the pool to buy a home here in LA, except for the prices. Some of our more highly educated, high-income individuals are moving further and further inland to maximize that residential investment dollar. That’s telling, in terms of just how much the cost of housing is a driver of population swings here locally.

Warren Olney: Do those folks become commuters?

Jordan Levine: A lot of them do. Folks are migrating further in, maintaining their jobs in big employment centers on the coast in LA and Orange County, and then upping their commute times. The offset associated with the inconvenience of commuting pales in comparison to the amount of savings you get by moving into a market that doesn’t have half-a-million-dollar median prices.

Warren Olney: What about rentals?

Jordan Levine: Rentals are feeling a lot of the same thing. It comes down to supply and demand. In Southern California, we just don’t have enough supply of housing—be it affordable housing, but more importantly, just housing full-stop. We see a lot of affordable-housing measures coming online for folks at the lower end of the income spectrum. Those might be too narrowly focused when you look at who’s moving out. These aren’t folks making minimum wage.

Warren Olney: Joel, you have been writing for a long time about how the single-family dwelling with a garden made Los Angeles what it is. That seems to be getting unaffordable for a lot of people.

Joel Kotkin: That’s exactly what’s happening.

People say, “I think we can densify.” But you lose so many of the advantages of being here the more you’re shoved together.

If you live in an apartment in Manhattan, you go down to the street and you have Manhattan. You have a subway system that the entire LA region, if it took every penny of tax dollars, probably couldn’t build. In New York City, you get a return on density.

In Southern California, you can live on the West Side in a dense area, but you still have to take your car for 90 percent of what you need to do.

Warren Olney: You teach, and consequently you’re in touch with a lot of millenials. Are they moving out to the Inland Empire? Is that a good idea for them?

Joel Kotkin: The growth in millennial population is overwhelmingly in the Inland Empire, as well as southern Orange County. Many can no longer afford Irvine.

Of course, you also have populations coming, particularly in Irvine, from East Asia—especially from China, where our housing prices and densities seem quite tolerable.

Warren Olney: Christopher, you’re the creator of an ongoing speaker series at Occidental College called Third Los Angeles, celebrating the city’s “profound reinvention.” Are we losing the promise of LA that Joel just mentioned?

Christopher Hawthorne: I think he’s right. The promise of Los Angeles always was, in the postwar decades, that you could afford to move here and get a slice of that LA dream even as a middle-class family. That meant a single-family house and a garden.

The experiment of LA in the postwar decades was building suburbia at this massive metropolitan scale. Now that the city is built out and housing costs have gone up so quickly, that dream is disappearing for a lot of people.

Warren Olney: Tell us a little bit about the First and Second LAs.

Christopher Hawthorne: I’ve been writing for a long time about LA moving into this new phase, the Third LA—trying to establish a post-suburban identity.

I think we tend to forget that many of the things we’re trying and struggling to add—a mass transit system; forward-looking planning; ambitious civic architecture and multifamily architectures—we produced in remarkable quantities in the prewar decades. I’m calling that the First Los Angeles: the beginning of modern LA in the 1880s through about the 1940s.

The Second LA is the suburban postwar Los Angeles.

Warren Olney: Is it a matter of not building a sufficient supply of housing? Not just low-cost housing, but housing, period?

Christopher Hawthorne: Joel is right that, at base, this is a supply and demand question. We’re simply not building nearly enough housing, at almost every range of the affordability spectrum, to bring down housing costs.

Largely that’s because there’s a huge amount of political opposition to it. There are a lot of single-family neighborhoods in a lot of parts of the city that did quite well in the Second LA. They’re reluctant to give it up. They’re anxious about moving into a different Los Angeles, and they want—I think for very good reasons—to protect that LA.

Warren Olney: We hear a lot about densification, particularly along the new corridors for mass transit. Joel said he thought that you don’t get return on density in Los Angeles. What do you say to that?

Christopher Hawthorne: I think we are in a period of limbo, as the Second LA is ending and the Third LA is beginning, where we simply haven’t built enough mass transit to make it a replacement for the mobility that we have in the freeways—from the Golden Age of the freeways in the late 60s or early 70s when it really was possible to move around the entire region.

It’s going to be 10 or 20 years before we have something even approaching a comprehensive, mature public-transit system. In the meantime, we're going to have this limbo where we see density increasing, but for many people, the drawbacks outweigh the benefits.

Warren Olney: Joel, are the amenities we’re used to in Los Angeles, including diversity, now available in other places where it’s cheaper to live?

Joel Kotkin: I think that’s true around the country. As people have left New York, LA, and Chicago to settle in what we used to consider second-tier cities, they brought culture with them.

Plus, immigrants are increasingly moving to such places. By some standards, Houston is a more diverse city than LA is.

Warren Olney: Christopher, what would you say to people who are having to “roommate up” but want to stay here? Are there places that are perfect for a person like that left in Los Angeles?

Christopher Hawthorne: My students at Occidental College talk about moving to Koreatown or Downtown after they graduate—places where they might have to live in an apartment with roommates. But that’s what I did in New York City when I was in my twenties: live in a little bit less space than I would’ve liked.

I think that’s a really significant and profound change in the way we think about LA. We’ve so closely identified it with elbowroom and space. Even if you’re relatively young and not making your peak income, you could afford to have room and then live in this great cosmopolitan region. That’s shifting.

LA was always a city of newcomers because we had so much growth—first domestic migrants and then immigrants from around the world. It was a city of homeowners. Now that’s been flipped. It’s more and more a city of natives and a city of renters. That has significant implications for how we see the city and how people from outside of California see LA.

Warren Olney: I understand that higher-income people are coming to Los Angeles and there’s growth in that part of the income sphere.

Jordan Levine: That’s one of the interesting things that flies in the face of the rhetoric we hear: that we’re business-unfriendly with a hostile economic climate in the state. But in fact, folks in the higher income categories are coming to California in greater numbers than they’re leaving.

Warren Olney: Christopher, is Los Angeles becoming a city of rich people?

Christopher Hawthorne: Particularly on the West Side and other wealthy pockets, there are a lot of people from around the world, particularly in China, who are looking to park some of their money in a market like Southern California. That makes the real estate here attractive, and just pushes prices up even more.

It’s a political challenge now—building more housing at all other parts of the spectrum except for that very high-end.

Warren Olney: Given that we’re in limbo moving into the Third Los Angeles, what do you think is the most likely outcome?

Christopher Hawthorne: The trend lines are very clear. The city continues to get denser and more vertical. We continue to build out the transit network. Traffic continues to get worse. This will continue.

That means a different attitude about public, shared, and collective space, and a different attitude about our architectural heritage.

One of the new things in this third phase is that we finally have time to catch our breath in a city that has never been able to consolidate its growth or think much about its own history. We’ll have a chance to slow down a little bit.

If more people are living in apartments, you have a much more active constituency for improvements to public space. People aren’t going in their garages, getting in their cars, driving to work, and spending time in that quasi-private space of the automobile. Even if you’re just walking down the street to a bus stop, or from your apartment outside because you live in a relatively small space, you care more about how the public realm is designed than somebody who lives in a private house with a pretty sizable garden.

- Log in to post comments