Wedged between a 15-lane highway and unincorporated LA County industrial zones, Ramona Gardens is a Boyle Heights community whose children suffer from asthma at twice the state average. TPR interviewed Legacy LA Founder Executive Director, Lou Calanche, and Community Conservation Solutions President, Esther Feldman, to discuss the Natural Park at Ramona Gardens, a green solution project initiated by the youth of Ramona Gardens that marries ecosystem science and state-of-the-art engineering with a community-driven design process to improve air quality and community health in one of the most polluted neighborhoods in Los Angeles. Calanche and Feldman share how community priorities were incorporated into the project design in collaboration with CARB and South Coast AQMD to fund air quality monitoring and pollution reduction strategies using AB 617. In Part 1, TPR speaks with Asm. Cristina Garcia on AB 617’s role and future in addressing environmental justice despite budget uncertainties.

Lou Calanche

“At Legacy LA, a big focus of ours is leadership development, especially with youth, and specifically for youth to come up with solutions to community problems.”—Lou Calanche

"As a community-driven design, married with ecosystem science and state-of-the-art engineering, we're putting the technical pieces together with what the community told us they needed."—Esther Feldman

Begin by describing the critical work that you have been engaged in for years that was the precursor to the Natural Park at Ramona Gardens.

Esther Feldman: Community Conservation Solutions has a great interactive web tool that identifies potential project sites on public land around Los Angeles, particularly in the upper Los Angeles River Watershed, that can both capture and reuse stormwater and urban runoff, provide carbon storage and additional local water supplies to help address air quality concerns, and particularly help improve communities who most need parks and green open space. This was the challenger hat had been posed to me by CARB chair Mary Nichols, to integrate all these elements. So, we hired a team of experts to help us do that and analyzed 500 different parks, schools and other public lands in the Upper Los Angeles River watershed.

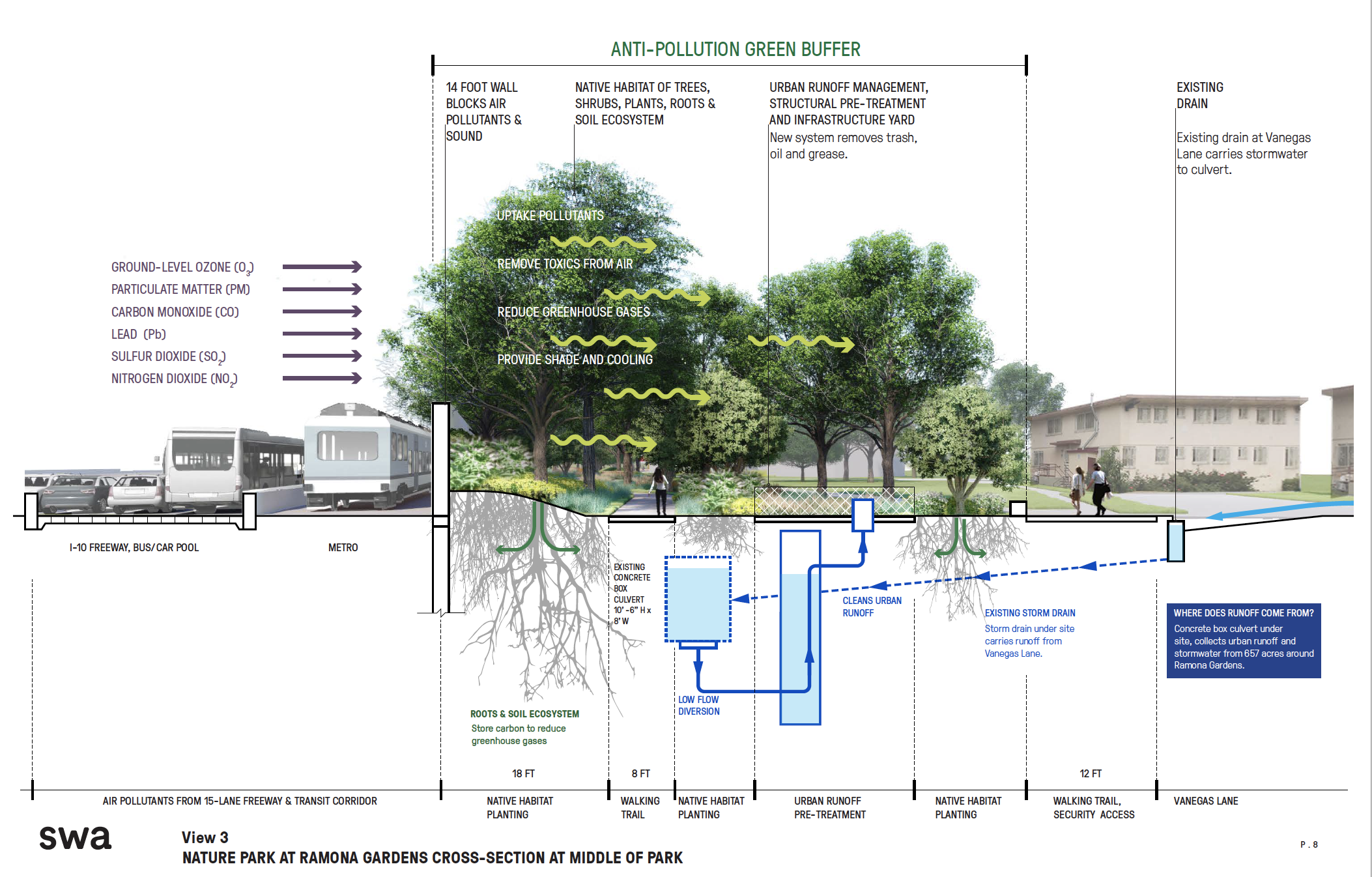

It turned out that this property in the Ramona Gardens Housing Development, which is publicly owned, was one of the highest priority sites in the entire upper LA River Watershed because it met all those criteria. It has a very large culvert—8’ x 10’ underground—with an additional 60” storm pipe carrying stormwater and urban runoff. There are about 700 acres around the Ramona Gardens Housing Development whose runoff and stormwater flows through the site. So, there's a water source that we could take advantage of.

The Natural Park project site is between the 1,800 residents living in Ramona Gardens and a 15-lane freeway corridor, with the 1-10, a high-occupancy vehicle lane, a bus lane, and Metrolink rail. This freeway right next door – plus the nearby 1-5 and 60 – makes Ramona Gardens one of the top 1 percent polluted communities in all of California. The need for public health improvements and using green space to help address some of the underlying public health considerations is extremely high.

Photo Credit: SWA and Community Conservation Solutions

Lou Calanche: Legacy LA’s mission is to provide resources and services to the community, but long term, it’s to build the capacity of the community to create change that benefits them. Through this process, our young people are participating in an effort where they are getting to see their dream of being able to improve community health through their own research.

At Legacy LA, a big focus of ours is leadership development, especially with youth, and specifically for youth to come up with solutions to community problems. That’s versus when I grew up in Ramona Gardens, and the experts always came and told us what we needed to do. So, our goal was to do our own community analysis and root-cause analysis to come up with solutions to problems.

One of the biggest issues was community health, and in particular, the asthma rates—which for children in Ramona Gardens is twice the state average from living next door to this highway. Our youth came up with what they call, Ramona Gardens 2020, with the goals that they wanted to achieve. One of those goals was to improve air quality. And their first instinct was to get rid of the freeway; they asked, why can't we put the freeway somewhere else? Obviously, that's not possible, so we asked them to dream about things that they could do to be able to improve air quality. And one of them was to create a tree buffer.

Our kids live steps away from the freeway. And there's a train—Metrolink—that goes right through. So, there's noise pollution on top of air pollution, and kids can see the freeway from their bedrooms. So, they came up with this green buffer, a tree-lined sound wall, which to them was just a dream until we met Esther.

We have done other environmental justice work like getting AQMD to actually pay for an air filtration system at the elementary school in the neighborhood. Our youth did that.

And our kids got the Youth Air Award; we were the first recipient.

Then we met Esther, and we started talking about creating this natural park that would be community-led. We began engaging the community in figuring out—not only how they could have this green space—but what could it include in the design to help mitigate the pollution from the freeway. Because again, you're putting a park next to a freeway. You want people to use it, but how can you include air quality mitigation efforts to improve air quality and improve community health?

So, this is not a small idea that you came together in partnership with Legacy LA, who did you draw in? And what were some of the features that you sought to include in the design.

Esther Feldman: As a community-driven design, married with ecosystem science and state-of-the-art engineering, we're putting the technical pieces together with what the Ramona Gardens community told us they needed. We did very extensive community outreach, working with Lou and all of her team. Legacy LA’s youth and adult leaders from Ramona Gardens did a door-to-door survey of every single house—all 500 residences—and interviewed in English and Spanish. We held several participatory community workshops to make sure that the priorities of people who live in Ramona Gardens—1700 people, including 700 kids—were really reflected.

Elaborate on what some of those priorities were.

Lou Calanche: Well, obviously, one was to create mechanisms to improve air quality—that was the overarching goal. But then, there were other features that were important to the community that were maybe something that the environmentalists wouldn't have considered.

For example, in the natural park, there is a swap-meet that the community created, like a little farmers market. Obviously, that was important to the community, and not just as a place to purchase food and items, but it was a place where people met, like a plaza, every Saturday. So, it was really important that it would be included in the park design.

They also wanted art. There are some murals that have been there for a really long time, and they wanted to preserve those. But really, everything was driven by what the community wanted.

How did you marry those design priorities with the science and technology?

Esther Feldman: The number one priority was to have a quiet place to escape the city and create beauty—natural places for children to play, a buffer from freeway noise, a walking trail, swap-meet area, and remove air pollutants from the adjacent 15-lane freeway.

We hired an air-quality expert team from WSP, a national leader on air quality. WSP analyzed a vast amount of local air pollution and other data to help us design the Natural Park to optimize the project’s air quality improvement potential. We found out where the prevailing winds come from—where those toxins are blown— and that ended up shifting all of our planting schematics. The result is a natural park that forms an anti-pollution green buffer with over 250 trees and tree-sized shrubs and 15,000 smaller understory plants, all of which work together and are adapted for conditions here. Included is a combination pollutant barrier and sound wall.

The Natural Park design is based on the native plants that used to be here 100 years ago before this area was developed. We’ve got living systems above and below ground, with roots that go down anywhere from 10 to 20 feet, to maximize carbon storage and provide year-round canopies of leaves, which maximizes their ability to uptake air pollutants.

The trees are placed strategically—raised as high as possible using earth mounds —so that they are doing the best job they can to capture toxins blown by that prevailing west wind. The earth mounds, or small hills then also become a part of the pollutant barrier wall.

Right now, there’s only a short cinderblock wall, about six feet high in most places, which does not block noise or air pollutants from the 15-lane freeway. The Natural Park calls for a real sound wall that you would see in any other community that requires a sound barrier to protect residents from adjacent freeway noise and polluttion. It will be 15 feet high.

The Natural Park also includes an urban runoff and stormwater capture and re-use component, where we divert all of the urban runoff and treat it underground. The cleaned runoff will be used subsurface to keep the marsh and meadow irrigated.

We’ve integrated a Plaza Verde, a Green Plaza that will be a multi-benefit gathering area for the weekly swap-meet that many people depend on for their livelihoods to put food on the table for their families, which Lou and the community really educated us about, as well as for other community events.

An important element of the Natural Park is a walking trail with benches where people can sit—a healthy place with shade where people can exercise. Walking is the number one prevention measure that people can take to reduce some of the serious underlying health issues like obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other ailments that afflict this community at a very disproportionate rate. This is important: asthma in children in Ramona Gardens is twice the state average. These are really big numbers that we can do something about.

Photo Credit: SWA and Community Conservation Solutions

Lou, talk about the involvement and learning experience of the youth and community members who were part of this planning process.

Lou Calanche: So, the work actually continues because we have the AB 617 grant, but early on in the conceptual design phase of the park, the youth not only did the surveys, but we also had really well-attended community meetings for Ramona Gardens. Folks got to see large-scale photographs of what could be, and then they actually picked what they wanted.

There was a lot of participation, which led to us apply for the AB 617 grant, part of which is to continue to build capacity in our young people to advocate for environmental justice and improved air quality. Then, the other component is for the technical team that's doing a lot of the research. For instance, one of the things that has come out of this is that our youth are now collecting on-the-ground data with air quality monitors that they wear around their necks

These high school kids did a preliminary survey last summer and came up with the hypothesis that where there's more trees in their community, the air quality seems to improve. So, they decided that they would do a larger study. We trained young people and also our adult leaders who went out to different sites in the community— somewhere there were trees and others where there were no trees because we live in an industrial area as well—and they developed a report they hope to present. The goal was to present to the Air Resources Board and AQMD, showing the data that they collected and how it’s being used to inform design and our advocacy efforts to get this park built, along with the high-level data that our technical folks are also collecting, but right now everything's on hold.

What are you learning?

Lou Calanche: I've learned a lot about air quality that I didn't know, but also about the importance of advocacy. The Air Resources Board is very interested in the success of this project. We're one of the priority communities, and they are interested in seeing this develop because there’s a lot of communities just in Southern California where freeways are built in proximity to the community. We have the capacity to collect data down the road, and we have a partnership with USC Environmental Health Sciences.

But for me, the important thing that I've learned is that you can build the capacity of people that live in an impacted area to be able to develop solutions for themselves if you

provide them the knowledge, expertise, and experience. You don't necessarily need to rely on outside experts to develop solutions. I believe that the outside experts can partner with the community to develop solutions to public health problems and this is a model for what can be done on future projects.

Esther, talk about the marriage with technical expertise and funding. Who were or should be the patrons of this project?

Esther Feldman: The state and L.A. County should be the lead funders to construct and maintain the Natural Park, with a variety of existing funding sources that could be combined. Cap and trade funding should continue to play a key role in moving the Natural Park from the design phase to construction. With the conclusion of the schematic design phase this summer, we will know what the estimate of probable construction costs will be. We'll have all of the AutoCAD drawings ready to be taken to the next phases of design, construction documents, permitting, and complying with California Environmental Quality Act. Then the critical question becomes, where will the funding come from to build this project? And as important: where will the funds come from to maintain the Natural Park, and to fund job-training and workforce development?

It's very difficult to get public funding for construction—even though that money is available —without having an entity who is willing to commit to the long-term operations and maintenance costs. This is a really important piece that doesn't get talked about very much, but it is one of the biggest barriers to building projects like this. It's not the money to construct it that's the barrier, it's having an entity that's got funding or access to funding to be able to operate and maintain it going forward. That funding is hard to come by, and we don't know where that's going to come from yet.

The funding to date has come from the Coastal Conservancy and California Air Resources Board through Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funds, the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Family Foundation, Southern California Gas, and the Union Bank Foundation. A critical partner here is the Mountain Recreation Conservation Authority; they are managing the grant from the Coastal Conservancy. If the MRCA had operations and maintenance funding made available to them, they would be a very powerful partner in helping build out and maintain the Natural Park at Ramona Gardens.

Who are the targets of opportunity to maintain and operate this incredible park that you're designing? Is it City Rec and Parks?

Lou Calanche: There’s money for maintenance and operations that's coming from County Measure A, and we're hoping that the Housing Authority finds money as well. I'm seeing this as an opportunity for young people to participate in building a park but also to learn new skills. We have a new type of park that's not going to be the typical grass park. What type of landscaping skills do you need? We're hoping that money for maintenance and operation also contributes to workforce development and employing youth to maintain the park.

Honestly, AB 617 and the grant we got from the Air Resources Board has kept this project alive. It has given us not only the momentum on the ground—because we're training young people to understand air quality—but it also has given us a stronger relationship with AQMD. One of our former Legacy Youth, who is now staff, was appointed to the AB 617 community coordinating committee.

The Air Resources Board is very interested in our project, has visited us many times, and has brought folks out to see the natural park. Their support has been incredible, not only in providing for the technical work, but also the on-the-ground community capacity building, which is the goal of the AB 617 grant.

What are the land use challenges surrounding Ramona Gardens, including the impact of our LA’s new zoning code for Boyle Heights? Is there an interface there? Is there an issue of how to benefit the entire community with the build out of the great park?

Esther Feldman: This property is an almost four-acre strip of land between the freeway and the residences, and is owned by the Housing Authority of the City of LA; it's completely within HACLA’s control, sandwiched between City of LA and unincorporated county.

Lou Calanche: Our youth had advocated to get our community included in the Cleanup Green-up Map, so that's a plus. For us, I would say the biggest land use challenge for us right now is being right at the border with the county. Ramona Gardens ends at the city limit on the east side, and on the other side—across the street from Ramona Gardens—is county industrial area, and that's been a little bit more difficult to navigate.

It’s full of industrial and warehouse use, which brings in a lot of trucks into the community. Land use wise, I would say that the county unincorporated area is probably the biggest challenge. They haven’t necessarily prioritized zoning, so that's kind of our next target. We've been working a lot with the city to ensure that there's more desirable uses around residential.

You're going to have a new Councilmember representing Ramona Gardens. What could they offer in the way of support?

Esther Feldman: Former Senator Pro Tem Kevin de León, and soon to be City Councilmember of this district, has a very strong vision for parks, open space, and greening. He fully appreciates, understands, and supports using ‘Nature in the City’ to improve public health, provide jobs, and improve communities with great needs, like those in Ramona Gardens and North Boyle Heights. He will be in a great position to direct critical city funding that could be used both for building the Natural Park and for permanent operations and maintenance, including recreation programming, interpretation, and workforce development, because Measure A earmarks almost half a million dollars per year, forever, to the Boyle Heights area. It is within the purview of the council member of the district to help direct where and how that money gets spent.

Lou, how important is it to have the support of the council and your local councilperson to do the work of this park’s build out but also for LA Legacy?

Lou Calanche: Fortunately, councilmember-elect Kevin de León has been a big supporter of Legacy LA, and a great supporter of Ramona Gardens. We have been working closely for many years, so we see this as the next big step in creating some long-term community health changes in Ramona Gardens. He is very in tune with the importance of environmental changes, and a continued partnership with his office is going to be incredible. This is not an easy project to do, but it will have such a great impact in the community.

Come the summer, what are the execution plans for Legacy LA and all your partners?

Lou Calanche: Right before COVID-19 and social distancing, we had planned to present the air quality data and the completed designs back to the community. Given that we're not going to be able to host those community meetings, Esther and I have been talking about innovative ways to do outreach.

We're thinking about how to create digital representations of all the designs and data, and have the community—on our website or on some platform—review all the designs and give us feedback. We would be working to get this information out, get more input, and build awareness through digital means versus having community meetings.

Esther Feldman: This summer, the schematic designs will be completed, and we will have the estimated costs and recommendations on how to phase the project. The critical next question then is going to be to our colleagues at the CA Air Resources Board, State Senator Maria Elena Durazo, and Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo: can you help earmark funding from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) for the Natural Park so that it can be built, operated, and maintained?

We do have a pandemic that's impacting communities, the city, and the region. It's put too many people out of work; it's changed the whole notion of how we interface with each other going forward; it's introduced public health in a way that's never really been at the top of the agenda; and lots of priorities are being shifted. How important is this park vis-a-vis the other COVID-19 priorities? If you were a decisionmaker, how would you rank this?

Esther Feldman: Absolutely top of the list, because the community that lives in Ramona Gardens is already disproportionately afflicted with many serious, underlying health concerns, which makes them the most susceptible and the most vulnerable to COVID-19. This is a community that is severely impacted by air pollution and unemployment, so creating the Natural Park- a project that can put people to work and help address those health concerns - makes it an exemplary project for how we improve urban communities with the greatest needs.

Lou Calanche: It doesn't change the fact that people live next to a highway and that they're impacted by environmental issues that are not their fault. It still should be top of list when it comes to solving some public health issues. I think we see the importance of public health even more now. As you mentioned, if you talked to folks about public health or community health, it wasn't something that people cared to talk about.

Now, there's awareness about the need to prioritize public health, so this is an opportunity to highlight a project that's community-driven that will address some of those underlying health issues that make people more vulnerable to diseases like this one. a public health necessity that should be top of the list.

- Log in to post comments