Bloomberg columnist Liam Denning describes the ways in which the fight for climate change and racial justice are closely intertwined, revealing how communities of color are disproportionately harmed by the effects of climate change, particularly air quality. In his piece titled “Fighting Climate Change Means Fighting Racial Injustice,” shared here with permission, Denning shares his experience visiting the city of Watts which ranks among the worst 5 percent of California’s districts in terms of pollution, as well as details the city’s history of civil unrest during the 1965 Watts riots and 1992 LA riots.

Liam Denning

"A person born in Watts can expect to live 12 years less than a fellow Angeleno lucky enough to be raised 20 miles away in affluent Brentwood. It’s the sort of shocking statistic where much of the shock value lies in just how unshocked we have become by such disparities in how people live and die." —Liam Denning

“You can’t let one segment of society become a sacrifice.”

Michael Méndez, an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, was on the phone talking about the protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd beneath a white police officer’s knee. But he was also talking about environmental justice and climate change. And he could just as easily have been talking about Covid-19, which has taken more than 100,000 American lives and, in the process, exposed gaping inequalities of wealth, access to healthcare and job safety.

Méndez has a new book called “Climate Change From The Streets” about the struggle of low-income and minority communities to have a voice in shaping environmental policy. It should be required reading for the most committed Green New Dealers and their opponents alike.

This fight for climate justice is already happening in one of America’s most iconic and charged settings: Watts, the Los Angeles neighborhood that made headlines half a century ago for another set of riots exploding out of systemic racism.

In late January, when it was still OK to get on a plane and meet strangers without masks, I spent a sunny afternoon there. My guide was Mac Shorty, who grew up there and is now a community advocate with the Watts Neighborhood Council, RePower LA and St. John’s United Methodist Church, among other local organizations.

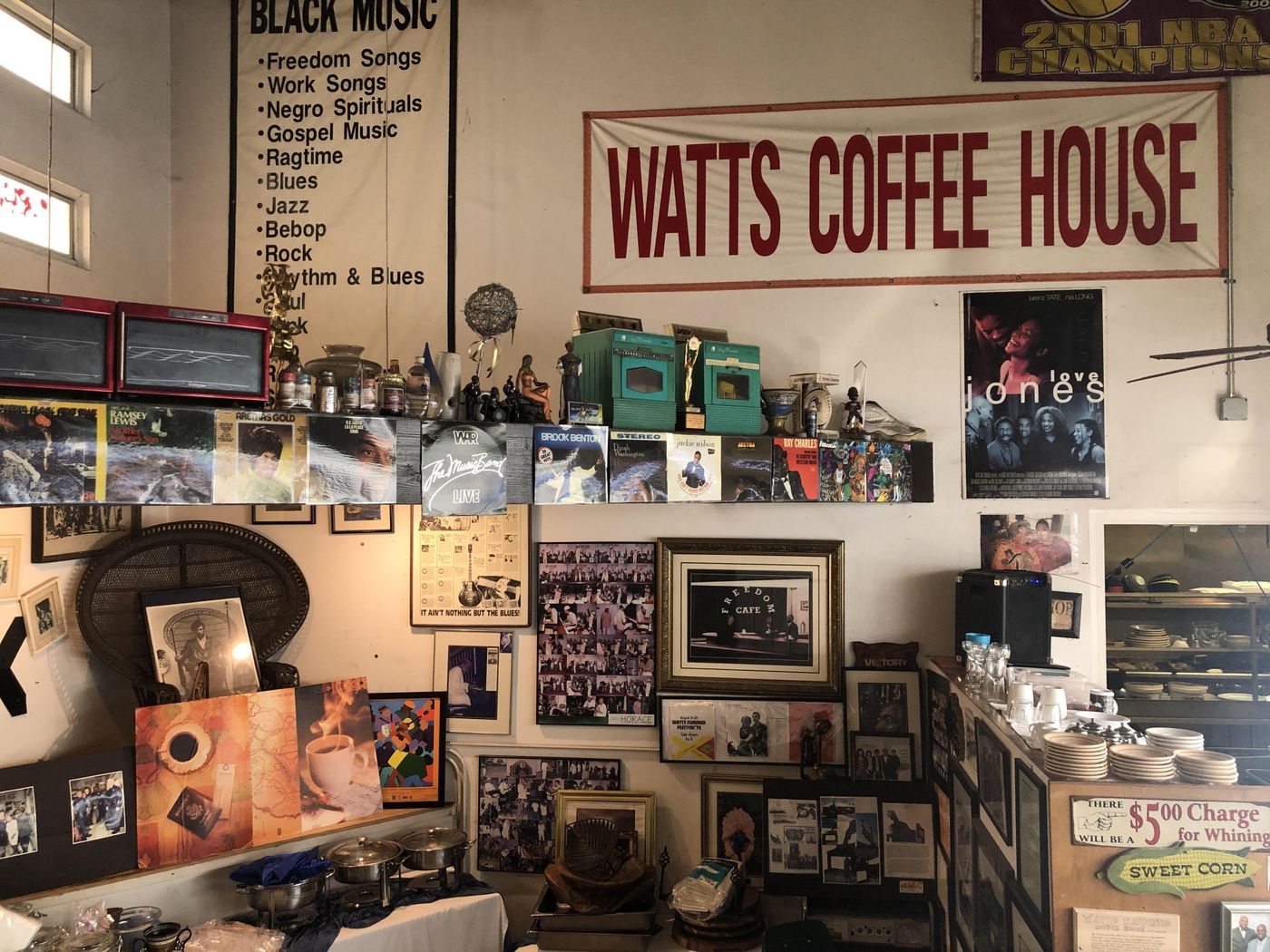

Watts’s scars, and triumphs, are visible in the fabric of the place. In 20 minutes, you can walk between two landmarks both built around the same time in the mid-20th century: Watts Towers, the monumental, Gaudi-esque artwork put together from found objects; and Jordan Downs, the decayed, low-rise housing project burdened by a notorious history of gang violence. In between is Watts Coffee House, a restaurant and black-history time capsule that traces back to the aftermath of the 1965 riots. Opposite sits Florence Griffith Joyner elementary school — named for the Olympian and former Jordan Downs resident — where Shorty points out blue sheeting stretched across the fence; put up, he says, to block children’s view of the street after a shooting outside. On the other side of the school is an urban farm called MudTown that stands out for its newness, sense of calm and sheer incongruity in south LA.

Watts Coffee House.

Photographer: Liam Denning

Predominantly Hispanic these days, though still with a large African-American population, Watts’s median household income is about half the average for California, and its poverty rate is about double. At one point, Shorty brought me by Atlas Iron & Metal Co., whose piles of scrap make it the sort of neighbor most communities would prefer elsewhere. But Shorty points out the people lining up with carts to sell what they’ve gathered, earning themselves a little extra income while clearing sidewalks of old appliances and trash. Crime is no longer as bad as it once was — Shorty’s mother was shot dead the year he enrolled in college — but remains a problem.

Contending with such day-to-day pressures, who’s got time to think about the environment? Yet that is where Shorty focuses much of his effort, ranging from remediation of dirty tap water to organizing Earth Day events to raising funds for installation of solar power in the neighborhood.

There’s no shortage of work to do. Watts ranks among the worst 5% of all California districts in terms of pollution 1 . Emblematic of this is the Jordan Downs redevelopment program, which unearthed contamination by lead, arsenic and oil products among other hazards, legacies of an industrial past and continuous neglect. It also sits by South Alameda Street, a busy artery linking the Port of Long Beach with downtown LA that forms Watts’s eastern boundary and suffuses the neighborhood with a steady dose of tailpipe emissions and heat.

A person born in Watts can expect to live 12 years less than a fellow Angeleno lucky enough to be raised 20 miles away in affluent Brentwood. It’s the sort of shocking statistic where much of the shock value lies in just how unshocked we have become by such disparities in how people live and die. When two housing authority employees stopped by Jordan Downs to say hello that January afternoon, Shorty warned them to rinse off the dust and soil from their shoes before going home to their families.

Dirt on a worker’s shoes, and what might be lurking within it, has little to do directly with our planet’s changing climate. Yet it has everything to do with actually doing something about climate change. This is the central message of Méndez’s book.

Opposition to climate action is made easier by the abstract nature of the threat; would that carbon dioxide was visible like a traffic haze. Absent that, it’s all too easy to ignore the problem or denounce measures to address it as job-killers. In the grand American tradition, this then gets overlaid onto existing divisions and stereotypes, such as pitting those old coastal elites worried about the polar bears against inland or inner-city workers just trying to put food on the table.

As Méndez lays out, such tension, and its resolution, has shaped California’s environmental policy. One of the most contentious aspects of the state’s landmark Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, known as AB32 and signed into law by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, was its reliance on a cap-and-trade mechanism for emissions. While environmental justice groups also sought to curb emissions, they pointed out that allowing polluters to buy credits to offset emissions let them pick and choose where actual cuts happen.

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger (seated) signs AB-32 on September 27, 2006, in San Francisco.

Photographer: David Paul Morris/Getty Images North America

That may reduce carbon emissions overall, which is good for the planet. But it also means communities close to sources that choose to buy permits instead of cutting remain exposed to other harmful emissions. As numerous studies have concluded, those places tend to be poorer or minority neighborhoods.

One analysis published a year ago by researchers from the University of Minnesota and the University of Washington compared Americans’ exposure to fine particulates versus how much pollution their consumption generates. It found non-Hispanic whites experience 17% less exposure to pollution, on average, than is caused by their own consumption. Conversely, African-Americans are exposed to 56% more than their consumption generates; the figure for the Hispanic population is 63% more. This is all of our environmental, health and — via that denominator of consumption — wealth disparity combined into a cloud of choking dust.

More than a decade after AB32’s enactment, environmental justice groups managed to force the passage of sister legislation to establish local air-quality monitoring and reduce local pollution. That same year, Schwarzenegger, a staunch defender of cap-and-trade when in office, told a climate-change conference in Germany “there aren’t enough conferences about people who die from cancer because they live too close to the freeway or to a port.” Addressing this disconnect, he added, was how “we can bring people into our crusade and then march forward in a much more successful way than we have.”

These under-served communities represent a well of support for broader action. A poll conducted a year ago by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that 49% of white respondents expressed “alarm” or “concern” about global warming. The figures for Hispanic and African-American respondents were 69% and 57%, respectively.

Securing their support for broader action means addressing issues on the ground, especially air quality, and incorporating the embodied knowledge rather than relying solely on experts. When Oakland announced in 2009 it would draft an energy and climate action plan, local activists took it upon themselves to map out the city’s neighborhoods in terms of exposure to such hazards as flooding, wildfires and poor air quality. Apart from shaping the plan, the campaign elevated local voices that might otherwise have been ignored.

It’s a priority for Shorty too. Asked about the most important issue in coming to grips with Watts’s environmental problems, he tapped his finger on the table for emphasis: “Lack of education.”

“If people were educated, they’d be able to fight for that clean air standard,” Shorty explained, adding, “When you go to these meetings, they’re using all these terms; but if you don’t know them, you’re lost.”

Exclusion stores up trouble beyond the environment, too. Talking about the 1992 LA riots, which blew up after the acquittal of police officers filmed beating Rodney King, Shorty observed: “If the community had a seat at the table when it came to training officers, they would understand how people who live in this environment react to situations.”

Part of Jordan Downs in Watts.

Photographer: Liam Denning

Beyond connecting high-minded objectives with street-level experience, the third, and vital, leg of this stool is using the established tools of institutional and economic power to translate all that into useful outcomes.

Cindy Montañez, raised in the San Fernando Valley and the youngest woman ever elected to the California State Legislature, is now the CEO of TreePeople, a non-profit championing sustainable urban landscapes in LA. She has worked to secure money raised by California’s cap-and-trade program for projects in neighborhoods such as Watts that address local sustainability issues: electrifying buses, planting trees and developing urban farms like MudTown.

Her aim is “resiliency,” not just in terms of environmental sustainability, but in renewing neighborhoods as healthier places with good jobs where people actually want to live — and developers actually want to invest, keeping the process going. Like Méndez and Shorty, she stresses the need to have a seat inside the room when addressing inequities of race and place: “You can’t really change it until you understand how to work the system and the economy to the benefit of communities that need it.”

One of the most striking aspects of last year’s Green New Deal resolutions was their emphasis on connecting social justice with climate policy. For all the controversy that generated, local groups in California have been doing exactly that for years. There can be no saving the planet without explicitly linking that to serving the neighborhood. That applies as much to a neighborhood like Watts digging out of its toxic legacy as it does to a mining town seeing its livelihood and organizing principle wither away — leaving a polluted bequest of its own.

Given everything that’s happened since January, though, this is more than a question of climate-advocacy tactics. Complex connections stretching from the microbial level to the atmospheric are embedded in the concept of ecology. But they often break in the face of politics.

A hallmark of opposition to climate action is its reliance on fragmented thinking. For example, fossil fuels are often touted as affordable. But what does that word mean really if it ignores the real costs of greenhouse-gas emissions? Burn your chairs for heat and pretty soon you’ll figure out the answer. Any effort to address these deficiencies with, say, a carbon tax is apt to draw accusations of socialism. Yet that’s what we have already, only in a pernicious model that privatizes the benefits of fuel production and consumption but spreads the associated costs of climate change and other hazards across the population (and not evenly, either).

It’s fair to say some joined-up thinking is in order, and the foundation of that is basic empathy — empathy for people we know, people we don’t know and people yet to come. The same impoverished, fragmented logic that ventures we can risk the planet to somehow save the economy was also evident in calls to risk Covid-19 tearing through America’s elderly population in order to do the same. It doesn’t take a genius to see what a virulent respiratory disease represents for neighborhoods with poor air quality, either.

This is burn-the-village-to-save-the-village thinking; sacrificing those other people or that other place so we can do our thing. I seem to remember a tedious trope about all lives mattering, but the only way they can all matter is through protecting the lives that are most vulnerable.

Leave any challenge to fester in the neighborhoods we don’t necessarily visit, and there’s a decent chance the consequences will eventually get in your face. That’s true of a virus, but it’s also true of racism, be it manifested in mere neglect or outright violence. And it's just as true of climate change and environmental degradation, which hit our most vulnerable communities first but ultimately care nothing for zip codes.

Selective sacrifice isn’t just immoral; it’s a fallacy. The necessary precondition of herd immunity against multiple ills is acknowledging you're actually part of a herd.

- Log in to post comments