TPR Archive: The April 1989 issue offers an op-ed by Daniel Garcia on L.A.U.S.D.'s development power, Douglas Ring's introduction to development rights transfers, and an interview with William Christopher, then recent appointee to the Planning Commission, on L.A. urban design.

L.A.U.SD.: What to Do, Where to Build?

By Daniel Garcia

Bigger than Maguire Thomas ... More powerful than the Planning Department… More involved in communities than the CRA and the CDD combined ... And less loved than the Housing Authority... The Los Angeles Unified School District is simply the biggest developer in the greater Los Angeles area. And... it can ignore the City's planning process at will.

The Building and Real Estate Department of L.A.U.S.D. is fairly small, yet it has the impossible burden of ensuring that there are sufficient facilities to house, as well as educate, the kids throughout a 700 square mile geographic boundary. If you understand what has happened to building anything in just the city of Los Angeles, you realize what a difficult task that is.

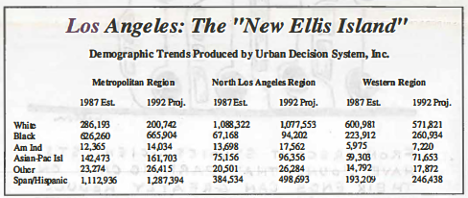

The physical development of the City has essentially occurred so that most of the developable lots are built up. At the same time during the course of 20 years, a very rapid and significant series of demographic changes have changed the ethnic and geographic composition of the City. Both the ethnicity and the number of kids per family have changed faster than the ability of most people to understand what those changes represent in terms of their educational needs. And the demographic change is certainly faster than the apparatus established to build schools could possibly respond to.

The School District is always trying to catch up; it is constantly in a position such as at Belmont High where there arc 5,000 kids, 1,000 of whom need to be bussed. In the next two years, the number of students bussed will increase to 3,000 if they don't do anything. In a service area beginning at Western Avenue, and running to Chinatown, there is a need for 4-5 Grammar schools, 1-2 Junior High Schools, and no place to put them that is readily apparent.

The School District receives its capital improvements funds from the State Allocations Board, but the system of allocation and the window of funding are not conducive to rational, long-range efforts. It is rather a series of spasms that result from the budget process. Further, the strains of Proposition 13 and 4 are now seen more than ever. Fearing that these monies will evaporate if they are not currently used, L.A.U.S.D. is often forced to select school sites in an unnaturally short period of time.

A serious problem therefore results because the time frame the School Board has to make decisions is different from planning cycles. A councilperson who wants to plan a district and meet with the community will prolong the City's planning process. This is exactly the antithesis of state regulatory pressure coming down on L.A.U.S.D.

Thus we see conflicting procedural impulses of a powerful nature -one is purely political, one is purely budgetary-pushing in opposite directions. Serious conflicts arise about how decisions should be made and what decisions are made.

The pressures upon the School Board-including the timing of its funding and the process by which they have to compete for funding with other jurisdictions-are sufficiently strong that cooperation with the City is not an ongoing component of its building program. Last year, Frank Eberhard, the Zoning Administrator, presented the Planning Commission with 40 possible school sites as well as an outline of criteria that should be used in school siting. The School District can ignore the criteria and the sites, since, under state law, it can do whatever it wants.

What needs to change? As time goes on, economic pressures continue, and land values go up, it will become increasingly difficult to acquire large lots for schools. Grammar schools require 6-8 acres, Junior Highs need 15-30 acres, while high schools require 30-35 acres.

These are massive takings and these standards seem to apply to school sites in developing areas rather than sites in an intensely regulated area. We have to reexamine how to redesign schools; there is nothing magical about a one story classroom.

And since many school acquisitions will displace some residents, we have to minimize the taking to the least extent possible. Recent legislation by Mike Roos was a first step in this direction but not nearly enough design flexibility exists under recent regulations.

In addition, the funding process for school sites needs to be made more flexible so that it can be compatible with the planning process. Moreover, there must be a will at both staff and Board level of the District to play an ongoing-not episodic role-with the Planning Department.

Finally, we need to plan in 10-12 year cycles. After the 1990 census, our planning should accurately project future growth. Even if we do not have any gains in housing units, our population will continue to change and grow. This is a problem which will not go away.

Daniel Garcia, former president of the Planning Commission, is a partner with Munger, Tolles & Olson

__________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________

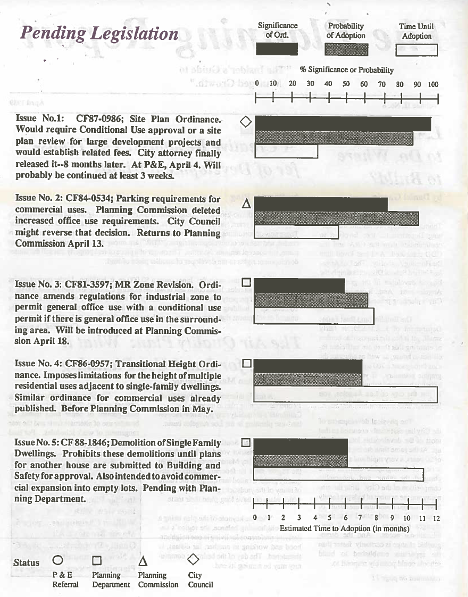

Insider Planning

By David Kramer, Editor

The Porter Ranch Specific Plan presentation by the Planning Department was cancelled from a recent Planning Commission meeting for fear that hundreds of protestors would arrive without the opportunity to speak. The specific plan, which has generated outcries from the community of Chatsworth/Porter Ranch, provides for 7.S million square feet of development-6 million more than is tolerated by the current plan. The soon-to-be released hearing examiner's report will make some modifications of the plan including more equestrian housing.

One ironic note from the public hearing is that perhaps the biggest complaint against the developer Nathan Shappell by the community was his building an Aliso Canyon bridge to complete Sesnon Boulevard; yet this would have been done as an exaction from the Planning Department!

The project will ultimately be a difficult test for Councilman Hal Bernson who has yet to become involved; the CAC he appointed approved of the project. What is he to do in an environment where most residents think this will become another Warner Center and are already blaming him for the growth?

The Planning Commission has begun to discourage the future use of interim control ordinances (ICO's). 25 ICO's currently exist in the city, and the Commission feels that unless there is a real urgency for an ICO to tightly regulate growth until a p1an is developed, no more ICO's. This position, however, did not stop an Alatorre-Molina-Ferraro motion to write an ICO for the entire Northeast District, which with 15,600 acres makes it the largest community plan in the entire city. The area covers Highland Park, Eagle Rock, Mt Washington, Glassell Park, El Sereno, and Atwater.

The ICO is designed to prevent out-of-scale development in the community while the community plan is being revised; projects must conform with the predominate density, scale and character of the neighborhood. This ICO could eventually become a model in the future; every time a community plan is initiated, an ICO would then be undertaken to protect the plan.

The creation of a mixed use development policy is proceeding full steam ahead. Weekly meetings with the Mayor's office, the Planning Department, the Zoning Administrator, and private sector representatives (Latham & Watkins) are brainstorming how to create a process to facilitate mixed use development projects without undergoing plan amendments or zone changes. The Mayor's office continues to be extremely enthusiastic about the policy.

The Citizens Advisory Committee for the Ventura Boulevard Specific Plan will unveil their 20-year plan in May. The CAC is currently deciding what parking requirements should be, and are considering raising those standards for office use. Growth along the Boulevard will be monitored by traffic generation.

While the community plan revision process is starting, the Planning Department is pursuing an ordinance that bans plan amendments for a certain time once a community plan is written. This ordinance could prohibit batching cases for up to five years; criteria are currently being written for what can and cannot be filed for a plan amendment.

A specific plan for Valley Village in North Hollywood will come before the Planning Commission on April 27. Similar to the transition housing ordinance, this plan attempts to protect single family homes adjacent to multi-family residences and commercial uses. The plan would not only lower height restrictions for these uses but will also establish a design review process.

A recent Bernson-Braude motion stated that all expanded uses of industrial and commercial uses be required to get a Conditional Use permit. The Planning Department is consequently thinking of including this motion in the Site Plan Review Ordinance. While the SPRO requires that all major projects over 40,000 square feet be reviewed, the ordinance might be amended so that expanding industrial and commercial projects under 40,000 square feet must meet certain criteria as well.

The Planning & Environment Committee recently approved the ICO which restricted development in the Hillside. The ICO was approved with much less fanfare than greeted it at the Planning Commission.

The Central City Association's Political Action Committee has endorsed Lyle Hall in his campaign against councilperson incumbent Emani Bernardi. As we indicated last month, this is the race to watch in the April election.

The State Board of Education has authorized a fee increase on developers to adjust to inflation. The Los Angeles Unified School District can now increase development fees which fund school construction. Residential development fees will rise from $1.53 to $1.56 per square foot, while fees on commercial development will increase from 25 cents to 26 cents per square foot.

The latest housing developers in Los Angeles are the Los Angeles Archdiocese, South Central Organizing Committee, and the United Neighborhoods Organization. $27 million is expected to be raised to construct 500 low-cost homes on a 25-acre site called Nehemiah West. Who says there are no answers to the housing crisis? The Archdiocese itself has pledged $3 million to the residential development

Councilman Michael Woo recently proposed significant rent control changes including calls for renters to be paid interest on their security deposits; for eliminating evictions for substantial renovation; and for restricting the ability of landlords to pass on the cost of capital improvements to their tenants.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________

‘Tis An Ill Wind, A Creative Response: The Transfer of Development Rights

By Douglas Ring

Even the no-growth movement, which has been bedeviling the real estate industry for the past several years, carries with it some new opportunities for the canny real estate investor. These new opportunities go by a variety of names; sale of air rights, transferable development credits, and transfer of development rights (''TDR") are among the most common. By whatever name, the concept remains the same. The owner of a piece of real property can sell the unused development rights to the developer of another piece of land.

Consider this example: Jones owns a 50,000 sq. ft building. Under current zoning and development rules, Jones could tear down the existing building and build a 100,000 sq. ft building on his property. Smith owns a similar piece of property on which he could build a 100,000 sq. ft building. Smith would like to build a larger building. Smith purchases the unused development rights from Jones. Smith builds a 150,000 sq. ft building. Jones is given the “benefit” of his unused development rights in the form of a cash payment.

These TDRs are, in large part, the by-product of the enormous increase in government regulation of the real estate industry. Prior to the recent surge of government regulation, property owners had the general ability to obtain approval for the construction of almost anything that market conditions would otherwise justify. With the rise of stringent land use controls, the cost and complexity of obtaining permission to build has significantly increased the value of all development rights and has created a market of those development rights independent of the land to which they were attached.

Transfer of development rights while conceptually uncomplicated is, in practice, no place for the unsophisticated buyer.

The first problem facing the prospective buyer or seller is defining what is to be sold. Unlike the sale of real property, which can be defined, drawn, and even staked out by a good civil engineer, development rights, prior to their use, have an almost mystical quality. There is no simple solution to the definition problem. The cooperation of the city attorney and planning director in smaller municipalities will be invaluable.

Some jurisdictions, like the City of Los Angeles, have begun enacting ordinances regulating the transfer of development rights. These ordinances assist in defining the interests to be transferred. Most jurisdictions do not have such ordinances. Careful legal drafting and close cooperation between the buyer, seller, and City will be necessary to protect all of the parties’ rights.

Even after the interest to be sold is described, the process for consummating the sale may be complicated. Unlike the sale of most real property interests, which can be transferred through an escrow, this transaction requires concurrent governmental approval. The buyer and seller are, in essence, transferring a government permission to build between each other. A sale without the blessing of the government agency carries with it inordinate risks. In those cities which have enacted ordinances which permit the transfer of development rights, the ordinance will spell out the procedures. Many cities are either unfamiliar with the concept or have no formal procedures for permitting such exchanges. In such municipalities, the buyer and seller may be obligated to educate both the public as well as the pubic officials before being able to consummate the sale. Traditionally, such transfers will require a public hearing before the Planning Commission and/or City Council. In Redevelopment Agency areas, approval of the Agency Board will also be necessary.

California State law has not yet identified or codified the transfer of development rights. This opens the door for both creativity and confusion. In many cases, the pioneer in the purchase or sale of development rights will be working together with government to define the procedures while completing their transaction.

Adding to the complexity of these problems is the absence of a pricing schedule. While the purchase and sale of real property is always the subject of negotiation, the negotiations normally are "controlled" by similar sales. Since few transactions of the sale of development rights have actually been completed, it is too early for the industry to have developed a set of “comparable sales” to use as an index for such transactions. Each transaction must be, therefore, negotiated in a far less defined environment than is traditionally the case for real estate transactions.

Determining price for the buyer will be a less complicated process than for the seller. The buyer, who is purchasing the ability to build additional marketable space, can use the same return on investment standards as would be applied to any other real estate purchase. The seller, however, is selling an "extra" which is less definable and less measurable for him than for the buyer. The seller's task is complicated by the government approvals. Most approving government agencies will require the payment of a fee for approving the transaction. Those fees are also subject to negotiations. The amount of the fee paid to the government agency will reduce the amount of money that the seller can command for the sale.

The newness of the market for transfer development rights also means that the real estate brokerage community has not yet developed a simple system for bringing buyers and sellers together. Very sophisticated real estate brokers are beginning to talk to their clients about marketing surplus development rights. Despite these conversations, no listing procedure has been developed. Both buyer and seller have to seek each other out.

Lastly, title companies, lenders, accountants and lawyers have not had a stream of transactions to use as benchmarks. Traders in development rights will have to educate those parties as well.

Will the benefits justify the effort? The answer is a qualified yes. For the sophisticated real estate investor, the transfer of development rights offers a unique opportunity. For the seller, it offers a chance to maximize the value of his property by selling space he has not used and is not intending to use. For the buyer, it permits the opportunity to increase the development rights of a project less expensively and with fewer complications than traditional land use approvals would permit. For both parties, it is a process well worth the effort.

Douglas Ring is a partner in the law firm of Shea & Gould. He serves on the Los Angeles Transfer of Development Rights Evaluation Task Force.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

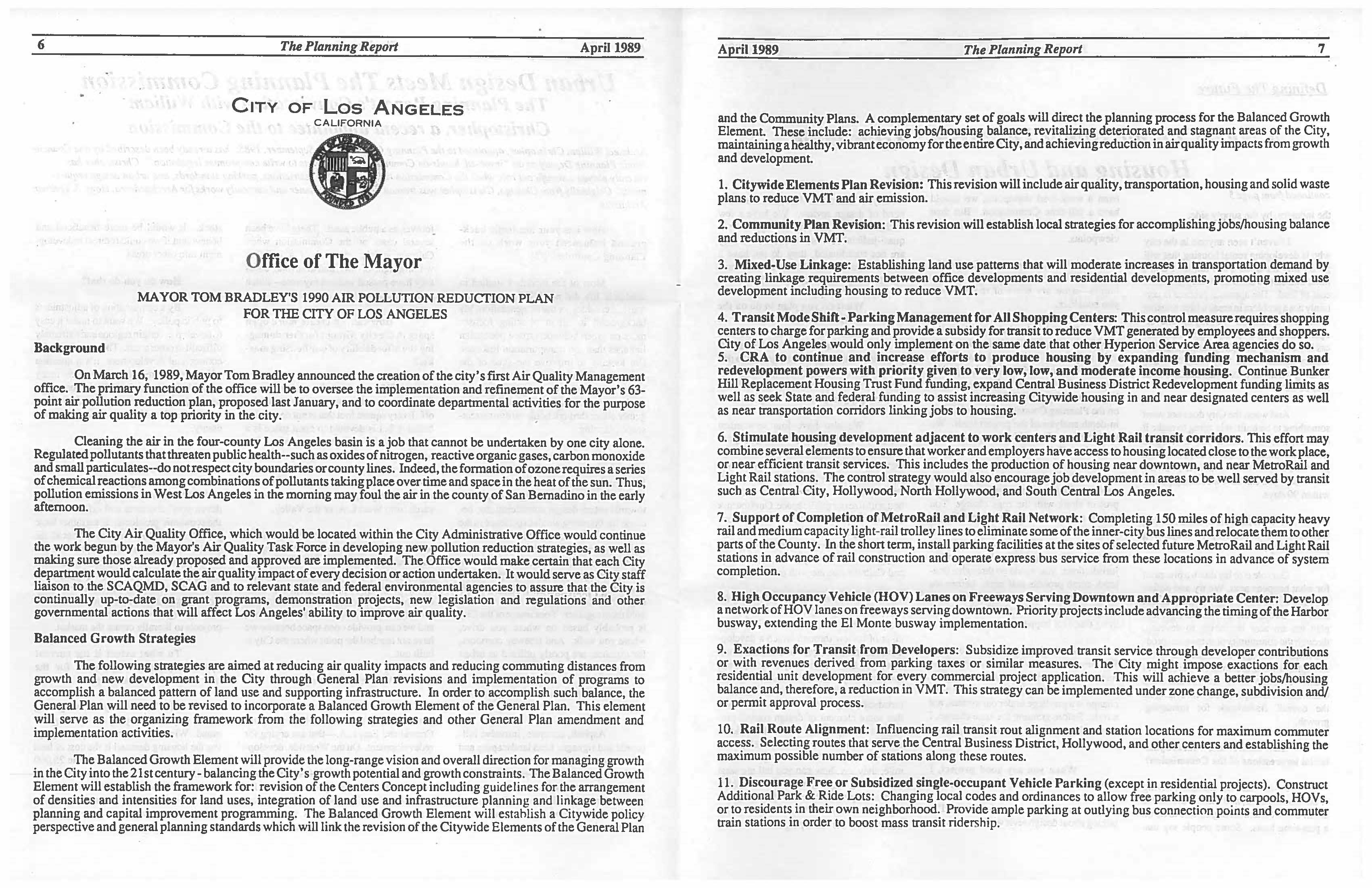

The Air Quality Plan: What it Means for Land-Use Planning

By Councilman Marvin Braude

A nearly unanimous vote last March 17 on a far-reaching plan to improve Southern California’s air quality may put a new face on land-use planning in the Los Angeles basin.

When the South Coast Air Quality Management District voted 10-2 to adopt a revised Air Quality Management Plan to help the region meet its federally mandated airquality goals, it called into question the future of many of the yardsticks and assumptions by which planners have long plied their trade.

With the keynote of the plan being a better jobs/housing balance, the region's underlying preference for living in one neighborhood and working in another, far distant, is threatened. The day of the bedroom community may be nearing its end.

The plan also proposes other significant societal changes such as the encouragement of better mass transit, the broader use of alternate fuels and the rearrangement of work schedules. For land use planners, though, the plan’s implications have yet to be defined in detail.

From a planning perspective, the big culprit in the battle for clean air is urban sprawl, which gave us freeways, single family neighborhoods stretching in all directions, low-rise buildings and hour-long commutes.

In a region where sprawl already exists, options available to combat it are limited to what can be done to already-developed communities. For the most part, planners need not be concerned with changes in what is permitted on vacant land; such changes will pose few problems to planners because their canvas is blank. The real questions is how they will approach reducing traffic by land-use strategies in an already built-up city.

For most of us, our longest and most frustrating drives are to work. We have accepted the grind of commuting as the price for suburban living at lower densities. To reduce commuting, then, and to lessen the amount of pollution produced by fuel that's inefficiently burned in rush-hour traffic, home-to-work drives have to be shortened. That’s why a better jobs/housing balance is high on the AQMD’s policy agenda.

Under the plan, just as new business and industry will be lured to residential areas like Riverside and San Bernardino Counties, so will new tracts of homes at varying densities be encouraged in previously industrial zones.

Similarly, the plan will eventually require new businesses in job-rich areas (commercial or industrial zones) to open satellite work centers in predominantly residential parts of cities.

In the latter neighborhoods, changes in city laws may also be needed so that employees can work at home, via teleconferencing. On the other end of the teleconference wire, work sites in new large (25,000 square feet or more) businesses-work sites made possible by additional code revisions-will receive from and transmit information to, these home-quartered employees.

As much as any other single item, traditional, on-site parking lots may become endangered species as the AQMP unfolds. Throughout the plan, references are made to reducing the amount of parking required for future commercial developments, to charge for parking and to encourage more workers to use mandatory ride-sharing incentives. With less land required for parking, planners can be more creative and imaginative in designing new structures. Higher density, with more jobs per site, can result; however, lower density, with more attractive design features and lower construction costs, could also be a consequence.

Cities in Southern California may be forced by air pollution-induced restraints to become far more decentralized in the next two decades, and more like the small towns many of us knew in our youth. Neighborhood shopping rather than large malls, families with one or no cars and more greenery and less asphalt may all result from the AQMP's application to our lives.

Each of these will mean major changes, both in the laws that govern land use and in the way we carry out our lives. Planners will have a large role to play in both, and with skill and imagination can make our transition to a simpler, cleaner society less painful.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Urban Design Meets the Planning Commission

The Planning Report’s Conversation with William Christopher, a recent appointee to the Commission

Architect William Christopher, appointed to the Planning Commission in September, 1988, has already been described by one Councilperson Planning Deputy as an “involved, hands-on Commissioner who wants to write compromise legislation.” Christopher has recently played a significant role when the Commission reviewed hillside restrictions, parking standards, and urban design requirements. Originally from Chicago, Christopher was trained as an urban planner and currently works for Arechaederra, Hong & Treiman Architects.

How has your academic background influenced your work on the Planning Commission?

Most of the models I studied in academic life did not have to deal with traffic, set asides, or traffic generation. My background in urban planning focuses more on green belt/open space pedestrian linkages than on transportation linkages. I'm looking to improve the state of the pedestrian linkage in Los Angeles and begin to consider open space as a network-something that can be linked together either through boulevards or streetscape planning.

We are only now building an urban design staff within the Planning Department. It is essentially a first. I intend to steer the Planning Commission towards urban design considerations, because the one thing we all experience in the City on a daily basis is what we see. We look at the streets, we walk down the sidewalks, we look at billboards and advertisements, and our perception of the city is based not so much on the buildings and the architecture as much as it is the streets that hold them together. Your image of the City is probably based on where you drive, where you walk. And freeway corridors, for instance, are poorly utilized as urban connectors.

And what is that image people see?

Asphalt, concrete, intrusive billboards and signage. Less landscaping and recreational facilities. Caltrans currently has a program to sell off excess freeway land for commercial development in order to generate public funding. This is extremely short-sighted, because once property goes into private hands, it is lost forever as a public asset. There have been several cases on the Commission when Caltrans sought approval of a building within a right-of-way, and in several cases they have passed without my vote-much to my regret

How can we create more open space in the city without further damaging the affordability or our housing market?

When we are discussing private development space, we really have a tradeoff. Every square foot that is not devoted to building but is devoted to open space is a lost square foot of housing profile. But people we are warehousing in private developments held in trust for low and moderate income families are entitled to the same amenity rights of those with backyards from West L.A. or the Valley.

In fact, the low-income elements of the community probably need that space more than other groups. The debate I've had with Commissioner Ted Stein centers on how much open space requirement is too much? My contention is that there is still a significant amount of buildable lots, and we can provide open space because we have not reached the point where the City is built out.

Where can we build?

There are a lot of areas in the City where people can still build-in South Central and East L.A.-that are crying for redevelopment. On the Westside, developers are knocking down 16 unit buildings that were built in the 1920's around old courtyards and propping up stucco box R4 housing. I'm often told, "no more pink boxes." Such activity docs not have to happen where there is a reasonable housing stock. It would be more beneficial and benevolent if we could redirect redevelopment into other areas.

How do you do that?

By a combination of adjustments to public policy. We want to make it easy to develop in certain regions and extremely difficult in other areas. The same is true for commercial development; it's a question of how you address the system. How many set asides and exactions you lay on where you want to control growth versus how much you take off in areas where it's necessary.

The problem is that people don't want to build housing in some areas. And that's where housing trust funds and financial mechanisms come into play to mitigate developers' concerns and offset some of the economic problems. It's a rather large puzzle, and I'm not sure we can put all the pieces in place. It will require on the housing side the cooperation of our Commission, the Housing Commission, the Mayor, and a number of the leaders of the housing and financial industries, but we’re going to have to back some of these projects to literally create the market.

To what extent is the current approval process responsible for the lack of affordable housing?

I don't think the process is getting in the way of supplying the housing demand. What is more in the way in supplying the housing demand is the cost of land and the rental return. Most of the 25,000 families which increase our population each year cannot afford to live in the R4 units being built on the Westside or in the Valley. Their demand is not being met by the industry, by the supply side.

I haven't seen anyone in the city who is developing rental housing that will go on line for $300-$400 units. I don't think that can be done in the city given the cost of land. The approval process is certainly not a problem in areas where housing is intended to be built. The only time developers face an 18-24 month approval process is when they are going through discretionary action when they want to build housing where someone else doesn't want it to be built.

And when the City does not want something to be built, it is going to make it as miserable as possible for developers within the limits of the law. If you want to go where there is an R4 designation on the map today, you can have a building permit within 90 days.

What is the role or the Planning Commission, therefore, in adjusting public policy?

Our role is to lay down a blueprint for what happens next. We try and define the future path of the city through several actions-through the growth management plan we are now beginning to develop, through the community plan revision process which will begin in earnest this year, through the housing element of the General Plan. Through those frameworks, the Commission is empowered with setting up the overall framework for managing growth.

After six months, what are your initial impressions of the Commission?

I was under no illusions arriving at the Commission, and I know the task is enormous. It's almost impossible to do on a part-time basis. Some people say that from a work-load standpoint, we should have a full-time Commission. But then you'd lose the spontaneity from the outside viewpoints.

When you vote on each specific project-this zone change, that density bonus-what are some or the criteria you consider.

My priorities focus on how the neighborhood fit is. What is its relationship to its neighbors? Is it a good thing for the community at-large? Will the project impact the community? How can those impacts be mitigated? From there, my bent on the Planning Commission is to do more in-depth analysis of the project itself. We tend to have a lot of blank paper projects come through.

For instance, to change a project's zoning, you are not required to present a project along with the zone change. You simply supply the facts of the zone change, and in most cases you don't have to support the application with a project, a plot plan, or elevation of the project. In most other jurisdictions, you would go through a fine tooth comb process that says, before we will change your zone, you will have to· convince us that your project is the greatest thing that ever happened.

We don't do that for the most part. We leave that to further points down the line-the plan check process, for instance. We have to reestablish the fact that a zone change is a privilege under our system, not a right. Before granting the zone change, I want to be convinced you are doing a good project.

When you say good project, I assume you are talking about design.

I am talking about design, and I'm talking about design review as a process for the city. We have sort of stuck our toe in the pond of design review. We have a few design review boards that are operating as quasi-judicial boards around the city. They are not coordinated, they do not have a standard outlook on life, nor do they have written design criteria for evaluation.

What do you plan to do on the Commission about this?

My bent there is to coordinate the policies of the design review groups so that we have a rational system that professionals and landowners can come to and know they are going to be treated fairly.

We also have four new urban design positions in the Planning Department. We need to develop an urban design element for the City's general plan. We need to define our goals and some of the implementation procedures in order to better utilize our public space. Our first task is to develop a framework for this urban design approach. This urban design element will focus on the public rights-of-way, and how the City, State, the County, and Caltrans operate with public land.

When we consider individual development projects, we have to ponder design review criteria. Yes, it is another layer of review through which a development project must go, but I think without that layer and without subjecting a project to community values, the result tends to be chaos more often than not. Most other jurisdictions have come to the conclusion that some element of design control produces a better product. We have avoided it so far because most of the development community has not wanted to go the extra mile; they say, how can you tell me what my building is going to look life. And if a greater expenditure of funds is needed based on design review, that is money that definitely needs to be spent.

We don't want to end up in a place where nobody wants to live. And it's already beginning to happen. At some point we have to say enough is enough, we're going to do something to upgrade or arrest the decline in quality of life that we seem to be experiencing in Los Angeles over the years.

How will the proposed restructured committees or the City Council affect the way the Planning Commission will work with the C.R.A.?

My understanding is that C.R.A. projects will ultimately come through full review by the Commission. The implication for that change is that the Commission will have the opportunity not afforded previously for some public input on what the C.R.A. is up to in a physical sense.

The C.R.A is one of the most ambitious agencies within the City. Their ability to get things done given their framework makes them more productive than if they were operating in a complete fishbowl. This has several consequences. They do a lot of building downtown. They have impacts in the community that are not mitigated to a great extent.

There is significant housing displacement occurring near the Convention Center, and there is a greater need of housing within the redevelopment itself. It should be tied more directly to the displaced people. I would rather see a C.R.A. program building housing first, moving displaced residents l0 the new location, and then going in and removing some of the housing, instead of doing it after the fact.

Should the CRA take the lead in building affordable housing if the cap is raised?

Probably. They are set up to do that kind of construction. If they can do it, not necessarily as a house project but by private developers under funding agreements with the CRA, so much the better.

Speaking or large entities, bow can the Commission plan and select sites with the School District?

I don't know how you rein in the school district. Somehow, someway we've got to communicate with them and make sure we're all playing the same game. Without their input and their cooperation, no matter what our planning says, we might as well throw it out now and start over again because they have the ability to make it work or undercut it at will.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Los Angeles' Design Action Planning Teams

By Emily Gabel and Michael John Pittas

From March 3-7, 1989, a Design Action Planning Team met in the community of Los Feliz to develop plans and visions for the Olive Hill/Hillhurst neighborhood. The team, co-chaired by respected architects Brenda Levin and Rex Lotery, appeared later that week at the Planning Commission to detail its overview and implementation strategies for the area. Emily Gabel, who manages the Planning Department's Plan Implementation Division, and Michael John Pittas, an urban design consultant, were team members in Los Feliz and will continue to organize planning teams throughout the city.

Sequestered in the comer of a room, a developer, public official and a landscape architect are engaged in a debate: The developer argues for a construction intensity that will reach a “critical economic mass,” the public official insists on the value of preserving local areas, and the landscape architect points out that minimum lot depths are necessary to fit required autos and buildings. By tomorrow, this mini-dialogue will reach consensus and the debate will be over for the moment.

But now the heated discussion ensues surrounded by a jumble of tables, desks, and chairs strewn with maps and diagrams. In an adjacent room, students from graduate architecture and planning schools prepare a large base map of the existing buildings and streets in the two-mile study area. A xerox machine noisily cranks out enlarged copies of aerial photographs that will be used as the basis for analysis, and ultimately, illustrations in the final report. Lunch has been delivered in the next room; a donation from a local restaurant. In the back, four computers wait for an onslaught of thought and recommendations committed to paper.

This chaotic and frenetic atmosphere, belies a rational and orderly process at work. Two days ago the storefront was vacant. Yesterday, more than 40 people were interviewed from the local parish priest to the beat cop, along with homeowners, merchants, and the local children's librarian. By tomorrow, differences will cool, recommendations will be analyzed and the task of report production will begin. In two days following the group's work, first copies of the final report roll off the City presses in time for a formal public hearing and presentation to the City Planning Commission about the specific recommendations.

Thus, in less than one week a handful of L.A.'s best professional planners, architects, landscape architects, real estate developers and preservationists, came together voluntarily, to grapple with some of the more intractable local planning problems in the city. Augmented by Department of City Planning staff and students, the team's output is given substance and authority in a 60- 75 page fully illustrated report which gives precise direction and specific means of implementation for its recommendations. Thus far two areas of the city, Van Nuys and Los Feliz, have been the subject of this intensive analysis and forecast.

The teams are called LA/DAPT's (Los Angeles Design Action Planning Teams). They are co-sponsored by the City Planning Department and the Urban Design Advisory Coalition with technical assistance from the American Institute of Architects in Washington, D.C. A portion of the costs have been supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

This new local participatory process is in the nascent stage. Each successive study is expected to inform future LA/DAPT's. Thus far the benefits have proven considerable all around.

- The process is non-confrontational. Because those interviewed understand the volunteer “unofficial” nature of the LA/DAPT, their natural antagonism for public officials and government is avoided.

- It enables broader input. Given the informality of the input, a wider spectrum of issues can be brought up and dealt with. Few interviewees worry about who or what they “represent.”

- It validates professional planners’ work. Since there are few existing mechanisms whereby City Planning Department professionals can receive grass roots feedback, the LA/DAPT method can be a vital means of validating and modifying their ongoing work.

- It is a timely process. Because “planning” is perceived to be overly time-consuming, the shortness of the LA/DAPT process allows for almost immediate gratification and thus gains validity.

- It addresses neighborhoods comprehensively. Reaching beyond the narrow regulatory mandate of planning, the process welcomes comprehensive solutions integrating planning, recreation and parks, etc., in a synthesized "whole.” In addition, it allows free access to the planners without the inhibiting presence of one or more powerful well-organized vested interest groups. Thus neighborhood input tends to be more comprehensive.

- Its focus is problem-solving. Analysis and description are minimized in favor of action and implementation.

- The productions are immediately available. A substantial, easy-to-read report with diagrams, designs, and plans nicely interspersed throughout, is printed two days after the team completes its work.

- A synthesis of issues occurs which can become the basis for important follow-up work by all participants. The report covers not only traditional land use and zoning issues, but also issues of economic incentive, social service enhancement and even public safety issues. These broad spectrum of issues are synthesized so consequential planning can be pursued.

The benefits point to an opportunity for positive change to the City's participatory planning process and these techniques may be transferable to the City's new Community Plan Revision Program.

- Log in to post comments